Return to archive

title

Unbinding the TACK Publication (a digital publishing platform)

Author

Helen Thomas

Helen Thomas is sharing the script to her presentation on the TACK publishing platform held at the TACK Conference at ETH Zürich on 21st July 2023.

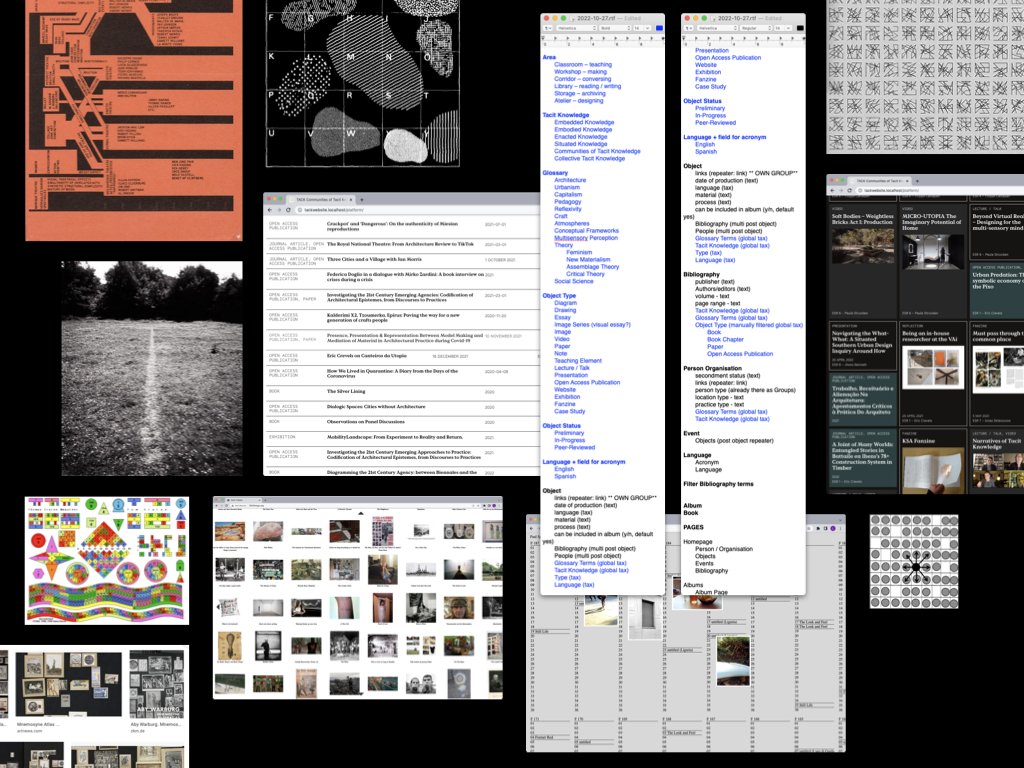

[fig. 1] Over the last year and a half, I have been involved on the periphery of the TACK project. My role has been to prepare and help create a way of gathering, editing, and disseminating content produced by the different participants in the project via a digital platform.

As I will show, this was done in a way that was open to and celebrating the special character of this ambitious collective work, while also meeting the project’s EU funding requirements. These included the publishing of a book and access to online training modules, as well as an archive conceptualised at the very beginning. A responsive approach was developed through direct experience, rather than through the application of a preconceived method. This way of proceeding was inspired by the elusive nature of the research focus embodied in the project’s full title: Communities of Knowledge: Architecture and its ways of Knowing, also described as Tacit Knowledge.

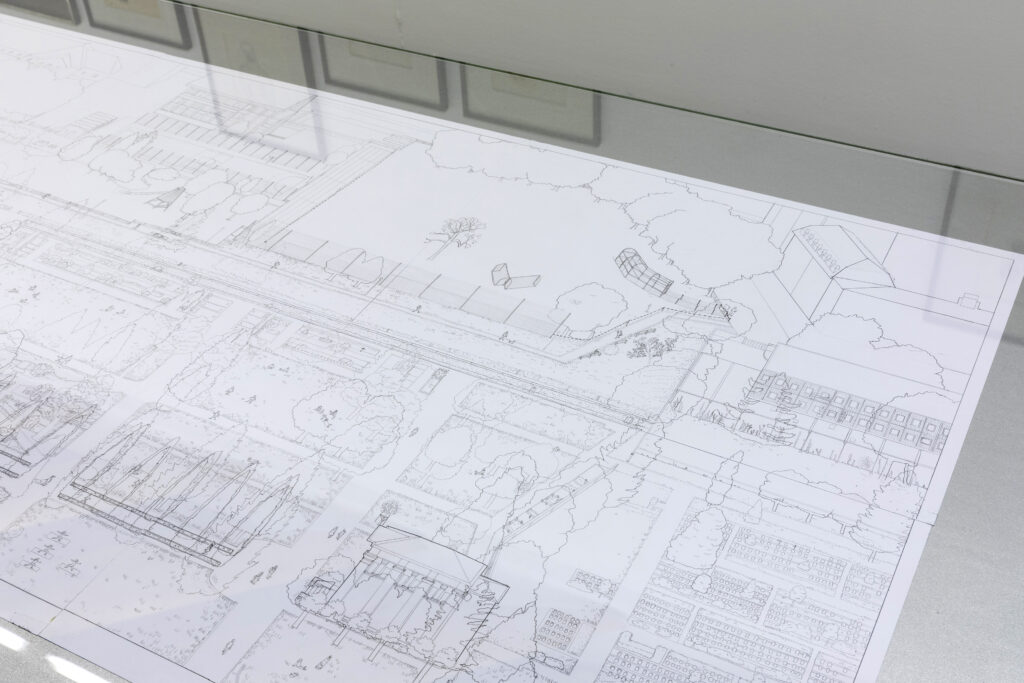

[fig. 2] The TACK network is composed of a group of around 40 individuals scattered across 14 European academic and cultural institutions and 9 architectural practices. They have been living – albeit mostly virtually, growing and producing together over a period of 3 years. This talk, and indeed the publishing platform itself, addresses the question of whether such a large and complex organism can contain, represent, and disseminate the sum of its parts in a single codex publication. I will use the term codex a lot to denote what we call a book, that is a physical object composed of a stack of sheets of printed paper, called pages, bound within a cover.

The interconnected complexity of the TACK network is not a problem, but an inspiration. We could see it, perhaps, as an opportunity for a diffractive approach. The task is to understand the TACK world itself from within and within its wider milieu by recognising the material objects and encounters it has produced and continues to produce. The same is true for its subject of study, the nature of tacit knowledge. To do this, the publishing platform as a mechanism has been devised. Its construction through adaptive feedback allows the meaning and interrelationship of the individual people and the objects that they produce, to be shaped and reshaped, and their meanings therefore constantly minutely realigned.

[fig. 3] The term Unbinding used in the title of this talk today refers to a release from the covers – hard or soft – and an ungluing of the spine of the bound codex book. In the words of Janneke Adema the alternative is “an experiment in reimagining the book itself as living and collaborative, as an iterative and processual form of cocreation.” In other words, publishing becomes a performative event enacted and enacting within an interconnected and relational situation. This active performance can be seen taking place both in the past and in the future of the present TACK publishing platform. That is, in the projective state, or design process, of its production and in the creative form of its consumption through the act of navigation and readership, but also selection and collection, where the user is invited to create their own Album from the Archive.

Throughout my publishing and editorial work, the idea of publishing a book online rather that in a conventional codex format evokes questions that recur again and again. Most of them are related to the sequence of material, specifically the fixed order of the chapters, but also on a micro-scale. This includes the numbered pages, the individual paragraphs and even the spatial relationships between sentences, footnotes, and images. This fixed and managed arrangement means that ideas, facts, and arguments unfold in a controlled narrative sequence. A similar question arises in the relationship between things, such as an author’s name and their academic specialism, an image illustrating a point, or an ending being conclusive.

In my imagination, the Argentinian novelist Julio Cortázar’s book Rayuela, or Hopscotch, always answers these questions. This novel of the 1960s has 155 chapters or parts, 99 of which are defined as expendable. These discrete fragments of the narrative can be read consecutively or according to a Table of Instructions, but equally, they can be read randomly. Conceived to evoke the unsettling nature of post-colonial existence, some take place in Buenos Aires, that is, ‘From This Side’, and some in Paris, or ‘From the Other Side’. The expendable chapters take place ‘From Diverse Sides’, that is in the imaginary realm of one side within the other.

[fig. 4] As the apparatus of Cortázar’s novel makes clear, post-colonial reality has multiple concurrent layers and a single definition is impossible. His proposal successfully destabilises the notion of a unitary reality. This brings me back to unbinding and the various constructive challenges that it makes to the unspoken rules of traditional academia. Some of these are embodied in the making and the material reality of the printed codex, and can, therefore, be used to interpret the process of making the publishing platform in an interesting way.

Fig. 4 shows Robert Darnton’s communication circuit from 1982 on the left, which describes the relationships between various aspects of a printed codex book’s production, propagation, and consumption. It shows how these books as physical and intellectual entities come into being in relation to their social and cultural milieus. This a model for the creation of and dissemination of a material, often fetishized, artefact that requires significant capital to produce. It is therefore easily controlled and allows a hegemony to flourish.

The image on the right of fig. 4 is taken from an ETH Library seminar on Open Access. This process of publishing, whereby research outcomes previously expensive to purchase become freely available online, reduces the amount of capital input and expenditure. Examining the diagram carefully, however, reveals a disrupted engagement with the commercial world outside academia, thus isolating it from the wider cultural and social realms of Darnton’s model. The participating community of writers and readers remains within its more purely academic field.

The majority of these theoretical ideas, it must be said, are being applied by me retrospectively to the TACK publishing platform, in a form of post rationalisation. None of the following informed the actual process itself, which aimed to work from first principles as far as possible, but also using references, a couple of which I will show you later. The intent was to respond as far as possible to sometimes clear and sometimes implicit frameworks that were both sought and provided. The EU funder requirements are acknowledged. Also important are the expectations and desires of the Early-Stage Researchers carrying out their doctoral research, and of the Editorial and the Executive Boards representing the whole TACK network.

[fig. 5] An important question, for me, when thinking about the motivations for creating a publication is ‘for whom is this being made?’ The answer embodies not only the imagined readership that we try to keep in our mind’s eye when writing, but also fellow participants in the publication’s construction, each of whom brings their own tacit knowledge and expectations to the table. For example:

– the figures and subjects that we are researching and introducing to the world

– co-researchers and peer reviewers

– the editors who participate in its form and detail through review and revision

– the publishers for whom it holds financial and social value

– and finally, the values that the authors themselves apply to it – professional, for example, and also financial, an increased social status amongst peers, intellectual development, and maybe, perhaps, ethical concerns

The form and process of the TACK publishing platform encourages these fellow participants to work together in a different way. I’m going to list a few underlying ideas connected to conventional academic publishing that are tested by this:

The first is that of individual authorship as opposed to collective or anonymous authorship. In academia, scholars are assessed according to the weight of their individual, single authorial output in the form of published articles, chapters, or books. Identifiable authorial output is considered essential for hiring purposes and for further career and tenure development, as well as for funding and grant allocations.

With the development of the TACK publishing platform, we have an artefact that in itself is co-authored. This happens through consultation, feedback and naming or tagging processes, which also provides a ground for collective authorship and nuanced definitions of terms and relationships. For the reader, the platform encourages an interactive, multimodal and hypertextual form of navigation and constellation forming. This provides a ground for remixing and juxtaposition of processes, findings, concepts, and authorship.

[fig. 6] In my abstract for this talk, I referred to Christopher Alexander and his research project and publication called A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction (1977) which is often cited as an important precedent for computer programming. The book has 253 patterns, or conditions, that work in relationship with each other to define environments for living and working, and for making collective settlements.

The left-hand image in fig. 6 shows a list of some of these patterns, which he later brings together in proposals, or constellations of patterns, as shown in the diagram and sketch in the middle, which suggests a design for a small garden. Culturally, the model has been questioned, because Alexander’s informing world view as a white, heterosexual, middle-class, nuclear family-orientated American man is specific, while the claims for the patterns are universal. The concept of a pattern language, however, provided a useful starting point for computer programmers in the 1980s.

In his Introduction to the book, Alexander makes the simple statement that “each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over in our environment”. Instead of writing programmes through accumulating code specific to individual problems, A Pattern Language introduced the possibility of computer programmes as simpler assemblies of pre-defined patterns or relationships.

This forming of identifiable patterns and modular thinking has various analogies in the TACK Publishing Platform. One of these is the creation of content objects as modules. These can incorporate various independent elements, such as moving images, text, code, and sound. This expanded media field provides greater possibilities for representing the thinking, research, and production of the TACK network over its 3-year period. This is reflected in taxonomical terms like ‘atmospheres’ and ‘multi-sensual perception’. The possibility to collect and juxtapose these modular objects expands the role of the user, especially in the making of Albums. Content is no longer simply received by the reader but can be traversed, constructed, and managed.

The influence of A Pattern Language is also reflected in the organisation of the objects on the landing page, or archive page – which can be browsed as a grid or a series of strips, as seen in the explanatory image on the far right of fig. 6, but also in the more granular relationships between the objects defined by the various search terms and taxonomies.

[fig. 7] The creation of taxonomical frameworks specific to TACK but generic enough to be understood by readers outside the TACK system was one of the principal co-created tasks in the process of making the Publishing Platform. The image in the centre of the slide shows a snapshot from the site’s content management system that reveals the different ways of identifying an object: Forms of Tacit Knowledge, Glossary Terms, Object Types, Statuses, Languages and Rooms. Each of these categories embraces a further set of terms.

Renaming and reorganising structures of knowledge is not a new phenomenon, as we can see in the image on the left of the slide, but as an underlying theme to our own experience of creating taxonomies I would like to introduce the idea of diffractive reading. This approach is based on a practice and concept of reading introduced by Donna Haraway and subsequently taken up further, predominantly by feminist new materialist scholars such as Karen Barad and Iris van der Tuin. In her book Meeting the Universe Halfway(2007) Barad explains the difference between reflection, a term which we are accustomed to, and diffraction.

Reflection as a metaphor for inquiry is characterized as a mirroring of reality involving extracting objective representations from the world. Diffraction, within the context of physics, involves the bending and spreading of waves when they encounter a barrier or an opening. Diffraction, therefore, as a metaphor for inquiry involves attending to difference, to patterns of interference, and the effects of difference-making practices.

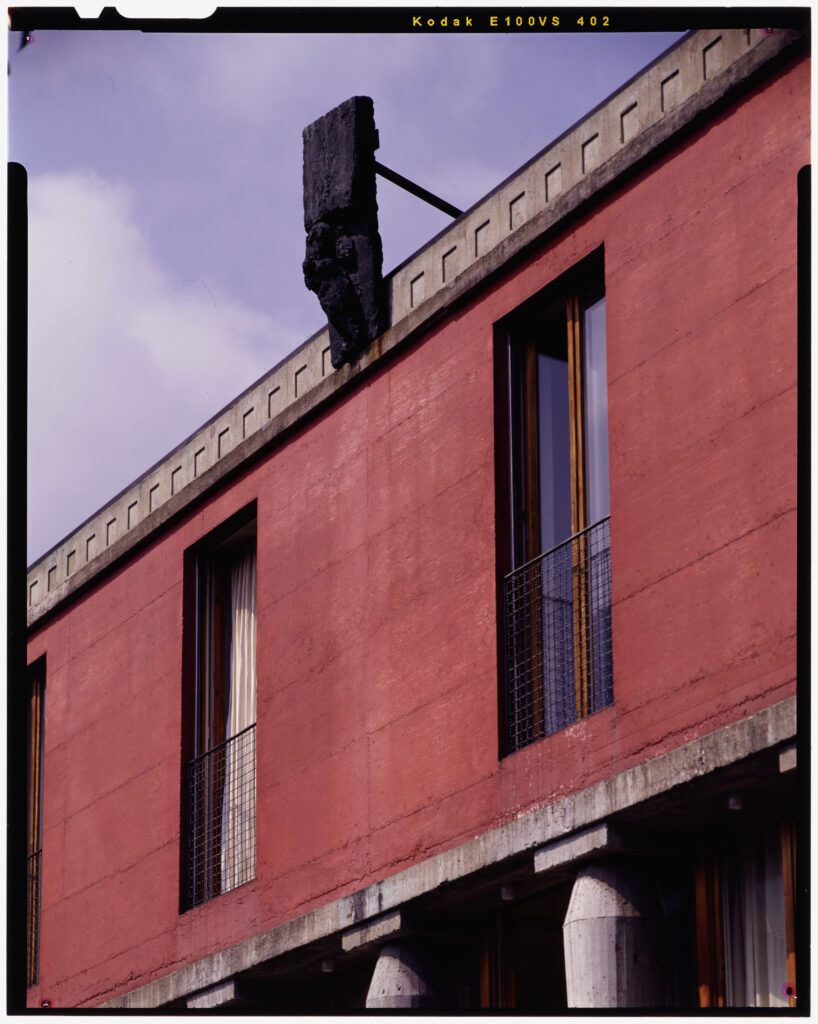

The image on the right of fig. 7 symbolises an example of diffractive reading that I have experienced. Called ‘reading-with’, it is being developed by the ETH-based Women Writing Architecture, Female Experience of the Built Environment 1700-1900 research group. Here, a text written in 1843 by Frances Calderon de la Barca about life in Mexico is read in four different ways by highlighting words denoting: the subjective I; the social we; place; and reference to secondary sources. Although simple to enact, this strategy enables interpretations and discussions that open out the text in many new directions. In this we can also see some of the intentions of Cortázar’s earlier experiment.

[fig. 8] The last theoretical idea that I want to introduce is that of versioning. As an artefact the codex book represents the best and final endpoint of a process of research, writing, editing and production. It is the version of record. The TACK Publishing Platform makes it possible to challenge this idea in two ways.

Firstly, texts and the research behind them can exist in different forms, with no single version being the definitive one. The slide shows the terms associated with the heading ‘statuses’ as they can be selected on the content management system. These include labels, which are strangely alliterative, such as ‘in-progress’, ‘peer reviewed’ ‘preliminary’ and ‘published’. The Publishing Platform includes work in development and different versions of research outcomes. On the right is the definition of the term ‘statuses’ as shown on the website, which was co-authored anonymously by a group of Early-Stage Researchers in the network.

Secondly, accepting that a work can have different iterations is a way to address the issue of authorship that I discussed earlier. By showing different versions of a text, its co-authored nature becomes more apparent – it is easier to see how it is commented upon, reviewed, and/or annotated in various settings by different (groups of) people and are thus necessarily the results of (reworkings of) inherently collaborative work.

***

The following images illustrate the process of making the TACK publishing platform brief:

[fig. 9 landing page of morethanonefragile.co.uk; a personal precedent]

[fig. 10: one of the project pages on morethanonefragile.co.uk]

[fig. 11: early experiments with print on demand, morethanonefragile.co.uk]

[fig. 12: proposed timetables for the brief-making process]

[fig. 13: extract from the design brief for the TACK publishing platform]

[fig. 14: TACK Antwerp meeting: workshop programme]

[fig. 15: Antwerp workshop: imagining journeys through the publishing platform]

[fig. 16: Looking at examples: the Feral Atlas: feralatlas.org, first landing page]

[fig. 17: Feral Atlas, looking at organising taxonomies: Anthropocene Detonators: Invasion, Empire, Capital, Acceleration]

[fig. 18: Looking at examples: womenwritingarchitecture.org, looking at organising taxonomies: Collections, Citations, Annotations]

[fig. 19: Women Writing Architecture: products and interpretations]

[fig. 20: TACK Publishing Platform: products and interpretations]

[fig. 21: TACK Publishing Platform showing how to make a product: the Album]

[fig. 22: A TACK Album]

[fig. 23: one of the interpretations of Tacit Knowledge on the TACK publishing platform]