Return to archive

title

Fotocronache Romane. The Representations of the City from Urban to Disciplinary Metaphors

Author

Filippo Cattapan

‘‘La fotocronaca è un modo di esprimersi più con le immagini che con le parole, le immagini possono essere scolpite, disegnate o fotografate, il mezzo non conta. L’urgenza editoriale moderna ha trasformato lo scalpello dell’uomo delle caverne in macchina fotografica. Una volta per conoscere la storia descritta sulla colonna traiana tutti dovevano andare a Roma. Oggi quella colonna è diventata un cilindro di rotativa e il lettore più lontano può riceverne a casa una copia.’’ 1 ‘The fotocronaca is a way of expressing oneself with images rather than words, images can be sculpted, drawn or photographed, the medium does not matter. Modern publishing urgency has turned the caveman’s chisel into a camera. Once upon a time, everyone had to go to Rome to learn about the history described on Trajan’s column. Today, that column has become a rotary press cylinder and the most distant reader can receive a copy at home.’ B. Munari, Fotocronache [1944], Milano, Corraini Edizioni, 1997, pp. 4-5. Author’s translation.

Bruno Munari, Fotocronache, 1944.‘‘Freedom, that fragile element of the human edifice, rests upon the imagination, both in the sense of illusion and in that of emancipation through the use of symbols. The Australanthropians’ world was already an imaginary one to the extent that it was founded upon the first materialization of what were in effect symbols taking the form of tools; so is the world of an average person of today all of whose knowledge is derived from books, newspapers, and television and who, using the same eyes and ears as our remote ancestor, receives the reflection of a world that has expanded to the proportions of the universe but has become a world of images, a world the individual is plunged into but cannot participate in except through the imagination.’’ 2 A. Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, p. 401.

André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, 1993.

At the beginning of Fotocronache, Bruno Munari grasped a crucial issue in a precise and concise manner: the impact that the techniques of reproduction and dissemination of images had on the culture of the twentieth-century, particularly with regard to the formation and transmission of knowledge. Consistently, Munari accomplishes this in a primarily visual way, through the eloquent association of two side-by-side images arranged on two adjacent pages, mirroring the central binding. The images are two black-and-white cutouts, one of the upper part of the Trajan’s column, and one of an unrolled 35 mm film, which clearly show the contrast between the weight of the ancient monument, firmly anchored to the ground, and the lightness of the new photographic support, mobile and dynamic (Fig. 1).

01. Pages 4-5 from Bruno Munari, Fotocronache [1944], Milano, Corraini Edizioni, 1997 © 1944 Bruno Munari

The Trajan column that becomes a roll film, as well as the caveman’s chisel transformed into a camera, do not just echo the bone thrown into the air that becomes a spaceship at the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’’s 2001: A Space Odyssey 3 S. Kubrick, director and producer, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968. but also the coeval anthropological theories of Claude Lévi-Strauss and André Leroi-Gourhan, which in turn exerted a decisive influence on the architecture of the following years. Images became fundamental tools for the construction of disciplinary discourse as well as for its transmission between different contexts, distant in space and time, in particular along the transatlantic route connecting Europe and the United States. In this context, as Leroi-Gourhan points out, images act both on an aesthetic and social level, allowing the diffusion of a series of formal canons and thus constructing the shared culture of the various professional and academic communities involved.

The imagery of ancient Rome is also intertwined with a series of visual themes and artistic practices which continuously reappear throughout the twentieth-century. These are especially the relationship between figure and background, or between void and solid, and the techniques of collage and assemblage. Both of them have their roots in Cubism, in abstract avant-garde as well as in Gestalt psychology, and take on new and different meanings during the course of the century. Munari’s artistic production shows how these themes were widely present in the culture of the time, for example in the 1940s collage Fotomontaggio metafisico, in which Munari inserts a blindfolded Bartlett Head of Aphrodite inside an engraving of the Pantheon in Paris 4 The engraving used by Munari represents Leon Foucault’s demonstration of the pendulum in 1851. , but also in the formal and chromatic experiments of 1950s covers of Domus. Such practices played a decisive role in the way architects looked at and then reworked Roman images in those years.

With different readings and applications, the engravings and ancient cartographies of Rome and of Hadrian’s Villa traverse the disciplinary theory of twentieth-century activating a series of fundamental processes and practices, as much formal as conceptual in nature. The city of Rome and its architecture are the point of contact between the dogmatic theory of Modernism and the open reflection of the post-war period, but they are also the themes on which the dialectic and often the opposition between the two is built. On the one hand, architects give legitimacy to their ideas by means of these ancient references, on the other hand the images themselves substantially determine these ideas through their own structure and composition. In one way or another, the fragmentary nature of Rome, with its various stratifications and the looming presence of imperial ruins, becomes the inescapable term through which to consider and rethink the composite space of coeval city.

The choice of visual materials and the modalities of their usage transform these distant archetypes into prototypes to be instrumentally applied to design. It is in fact through them that Rome becomes a repertoire of forms and of spatial structures that can be visually communicated and applied even at a distance and even without having any direct experience of them. These images and representations are thus not merely illustrations of architectural theory, but are in their own right a fundamental component of that same theory, an essentially visual and implicit kind of theory in which aesthetics and thought, form and content as well as figure and text develop together through a relationship of continuous and fundamental mutual exchange. ‘LA PAROLA É UN SURROGATO DELL’IMMAGINE’

5

‘THE WORD IS A SURROGATE FOR THE IMAGE.’ B. Munari, Fotocronache [1944], Milano, Corraini Edizioni, 1997), 6. Author’s translation.

[capital letters by the author] writes Munari in Fotocronache.

Thoroughly studying these documents, how they were selected and edited, traced, photocopied, and cut out in order to be included in the visual treatises, is crucial for understanding the influence they had on coeval theories and practices. The great themes of twentieth-century architectural and urban thought, the obliteration and then the rediscovery of the urban fabric, the celebration and then the rejection of the autonomous architectural object, all seem to have been conceived in this way, with and through images, in particular those of Rome.

The shift of epistemological paradigm that coincided with the emergence and the affirmation of these primarily visual cognitive modalities constituted a fundamental aspect of twentieth-century disciplinary culture: at a time when architecture was celebrating the absolute primacy of technical and scientific rationality, its removed counterpart, the imaginal, intuitive and analogical intelligence, was already re-emerging, and was to become crucial in the post-war years. In Gesture and Speech, Leroi-Gourhan writes:‘Four thousand years of linear writing have accustomed us to separating art from writing, so a real effort of abstraction has to be made before, with the help of all the works of ethnography written in the past fifty years, we can recapture the figurative attitude that was and still is shared by all peoples excluded from phonetization and especially from linear writing.’

6

A. Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech…192.

.

As cultural anthropology grasps earlier than other disciplines, the process of reunifying art and writing after a long separation will further accelerate from the end of the second world war, in parallel with the recognition of the inadequacy of modernism’s assumptions. The tacit and visual aspect of disciplinary knowledge was to increasingly take over from the explicit one of written and spoken discourse.

The map of Pirro Ligorio and the ‘jeu savant des volumes assemblés sous la lumière’

Vers une architecture, Le Corbusier’s pamphlet of 1923, already contains in nuce all the main themes of the theory of twentieth-century: the central problem of the city, the relationship with art, the use of ancient references to construct new theoretical perspectives, the very epistemological duality but also synthesis between imagination and reason. Before words, images are the crucial medium through which the discourse is articulated and of which the text, as in a fotocronaca, becomes a sort of secondary caption. Among this landscape of images, those of Rome assume a particularly relevant role in the book. It is in fact significant that, although Le Corbusier takes the Parthenon as his main architectural reference, ‘pure création de l’esprit’

7

Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, pp. 161, 175.

, it is to Rome that he dedicates the first and in some ways most extensive historical section of Vers une architecture, namely the first section of chapter 5, ARCHITECTURE, entitled La leçon de Rome

8

The reflection developed in the chapter was subsequently expanded by Le Corbusier with two articles published in the early 1930s in the journal Prélude, Esprit Grec – Esprit Latin – Esprit Gréco Latin and Rome, in which he addressed the theme of monumentality and of a “Mediterranean civilisation as the director of contemporary civilisation”. Prélude was ’the organ of an unspecified anti-parliamentary movement advocating Latin Europeanism’ of which Le Corbusier was one of four editors. See: M. M. Lamberti, Le Corbusier e l’Italia (1932-1936), in ‘Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia’, serie III, vol. 2, no. 2, , 1972, pp. 817-871.

.

While the Parthenon corresponds to the technical-artistic ideal of architecture, ‘un produit de sélection appliquée à un standart établi’

9

Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 106.

, the ancient city of Rome and its architecture are the true spatial model from which to design the twentieth-century city, because they apply the same ‘esprit d’ordre’

10

Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 124.

of the Parthenon, i.e. the same engineering rigour of coeval ocean liners, airplanes or cars, to the large urban scale, a quite different scale from the much smaller one of Athens and of Greek city-states, and which seems therefore comparable with that of twentieth-century cities.

02. Pages 128-29 from Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture [1923], Milano, Longanesi, 1973 © Longanesi & C.

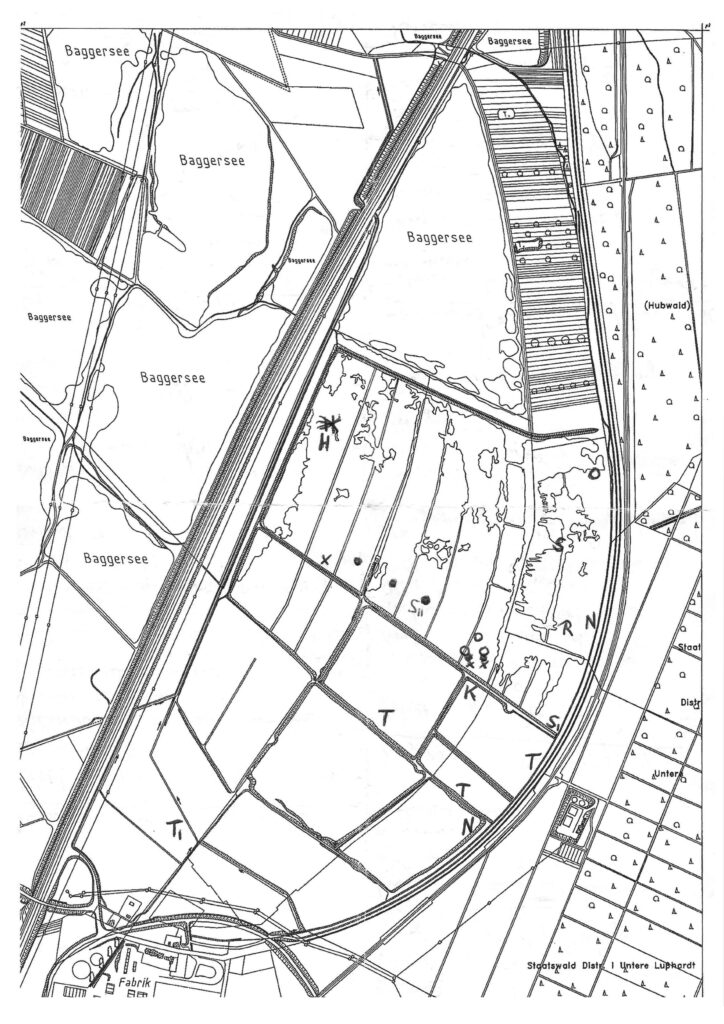

Le Corbusier almost literally quotes Pirro Ligorio’s drawing – this can be seen, for example, in the lines used to reproduce the water of the river Tiber – but he also makes two substantial changes. The first is the omission of almost all the minor urban fabric, already quite limited in this quadrant outside the walls, while the second is the curious insertion of a coliseum in the background, on the left, behind the large courtyard building identified as the Horti Domiti, i.e. the extra muros estate of Domitia.

The choice of Pirro Ligorio’s plan, and more importantly its targeted transformation, contributed to outlining the idea of a city as an open and airy field constellated with pure, primary volumes. To further emphasise this reading of Rome, the drawing is also flanked by a series of shaded volumes in axonometry: a cylinder, a pyramid, a cube, a square-based prism and a sphere. This is exactly the formal idea of architecture and of city that, as it is well known, crosses the entire text. Indeed, this idea appears to be closer to the Hadrian’s Villa, with which Le Corbusier significantly opens the Roman chapter, than to the imperial city represented by Pirro Ligorio, which on the contrary is extremely dense and congested, at least within the line of the fortified walls. From this point of view, Le Corbusier’s operation seems to be that of superimposing the serene spatiality of Hadrian’s Villa on the much crowded one of Rome.

As can be seen from the tourist maps of Hadrian’s Villa and St. Peter’s taken from the 1909 Baedeker guide to Rome and central Italy

11

See:Italie Centrale. Rome et ses environs. Manuel du voyageur, Leipzig-Paris, Karl Baedeker, 1909.

, Le Corbusier first experienced Rome in person, as a traveller, and was well aware of the congested and often chaotic nature of the city’s urban fabric, an aspect that was rapidly spreading in those years even to the suburbs.

12

As is well-known, in the first decades of the century Le Corbusier undertook a series of journeys that would be fundamental to his training as an architect. From 1907 to 1923, the year of the publication of Vers une architecture, he was in Italy four times. He spent long periods in Rome, from where he visited Hadrian’s Villa and Pompeii, and profoundly grasped the substantial urban and landscape problems caused by the rapid expansion of the city in those years.

This is perhaps one of the most significant examples on which Le Corbusier developed his aversion to the dense city in those years. ‘Rome antique s’écrasait dans des murs toujours trop étroits; une ville n’est pas belle qui s’entasse.[…] Décidément, tout s’entasse trop dans Rome’

13

‘Ancient Rome was crushed within walls that were always too narrow; a city is not beautiful when it is crowded […] Everything in Rome is definitely too crowded’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 123. English translation by the author.

he writes in the chapter’s introduction, and he is even more explicit in his subsequent letter of 1934 to the city’s governor Pietro Bottai, to whom he is applying for a possible commission in Rome that will never come to fruition: ‘J’ai été frappé de voir combien Rome pait en dévorant des banlieues magnifiques formées sages les plus beaux, les plus célèbres, aussi les plus émou vants. Là où une maison s’installe, le paysage est tué et Rome ainsi petit à petit perd tout le bénéfice de son site altier.’

14

M. M. Lamberti, Le Corbusier e l’Italia (1932-1936). Appendice B, in ‘Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia’, serie III, vol. 2, no. 2, 1972, pp. 860-861. All the documents included in the three Annexes to the text are preserved in the Archives of the Fondation Le Corbusier. In particular, the letter to Giuseppe Bottai is reproduced by Jean Petit, as the original cannot be found. See: J. Petit, Le Corbusier : lui-même, Genève, Edition Rouseeau, 1970, p.78.

From Pirro Ligorio’s original map, Le Corbusier thus adopted the plasticity of the volumes but removed all the crucial work of reconstruction of the urban texture, perhaps its most remarkable aspect, thus bringing the representation back to a stage that resembles the most schematic previous cartographies.

15

Concerning the progress in understanding and representing imperial Rome, see: A. P. Frutaz (ed.), Le piante di Roma, Roma : [s.n.], 1962. The maps of Rome prior to the Anteiquae Urbis Imago, even by Pirro Ligorio himself, mainly show the location of monuments without describing the fabric of the city. See in particular those by Domenico Gnoli based on the method of Leon Battista Alberti (1432-1434), by Piero del Massaio (1469), by Calvo and Egnazio (1527) and indeed by Pirro Ligorio (1553). This is a representative tradition that will persist in the following years, even if only occasionally. Thereafter, the general tendency will be to define in an increasingly precise and detailed manner the texture of the city’s minor fabric, the residential and productive fabric that fills the voids between the ruins, monuments and churches. In this regard, see for instance the maps by Stephen du Pérac (1574) and Mario Cartaro (1576 and 1979).

From this point of view, the plan of Hadrian’s Villa appears to be the perfect example as it represents a sort of ideal abstraction of Rome’s urban space, that combines a complex axial composition like that of the acropolis in Athens with the formal and volumetric richness of Roman monumental architecture. Le Corbusier writes: ‘Hors de Rome, ayant de l’air, ils ont fait la Villa Adriana. On y médite sur la grandeur romaine. Là, ils ont ordonné. C’est la première grande ordonnance occidentale.’

16

‘Outside Rome, with plenty of air, they have built the Villa Adriana. There they meditated on Roman greatness. There they gave order. It is the first great Western order.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 126. English translation by the author.

It is however, a very different order from that of the orthogonal grid of the ville radieuse, which is in fact closer to the model of the castrum than to that of the capital of the empire.

This model, significantly omitted from Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture, is the colonisation instrument par excellence, the principle of order exportable everywhere that is indirectly at the basis of the orthogonal plans of American cities as well as of his own hometown, La Chaux-de-Fonds. Nevertheless, it is also concurrently the ideal model that implicitly emerges from Vitruvius’ treatise, and that will later lead to the development of sixteenth-century utopian thought

17

In this regard, see in particular: E. N. Bacon, Design of Cities, New York, Viking Penguin, 1967, p. 216-217. Bacon refers in particular to the plan drawings from L’Architettura di Pietro .Giacomo Cataneo, published in Venice in 1567.

. The city of Le Corbusier constantly and ambiguously oscillates between these two extremes.

Again by means of images, in parallel with the development of his personal archetype of Roman spatiality, Le Corbusier also proposes a precise point of view on its constituent architecture. The formal autonomy and volumetric plasticity of the elements that compose this city is emphasised through the focused choice of images and their similarly targeted post-production. For the four sections of the Roman chapter, Rome Antique, Rome Byzantine, Michel-Ange and Rome et nous, Le Corbusier chooses only very narrow frames or context-free photographs that focus on the monuments, i.e. the pure volumes such as the Cestia pyramid, the Colosseum, the Arch of Constantine and the Pantheon, carefully avoiding to show the fabric surrounding them. To convey this idea, Le Corbusier drew on very varied and heterogeneous materials: not only art history books, such as Eugénie Strong’s Roman Sculptures from Augustus to Constantine 18 See:E. Sellers Strong, Roman Sculptures from Augustus to Constantine, London, Gerald Duckworth and Company, 1911, p. 328. from which he takes the photo of the Arch of Constantine, later edited and cleaned of both context and figures, but also and above all postcards, such as the reconstruction of the Colosseum by an anonymous author in 1910, and artistic photographs for travellers, such as James Anderson’s Pantheon of Agrippa number 477, a calotype from the second half of the 19th century from which Le Corbusier excludes any external elements, including the obelisk on the square. The photographic cut that Le Corbusier chooses for the Roman monuments is in fact the same as that of the photos of silos and industrial buildings included in the opening section, Trois rappels a messieurs les architects.

In addition to the medium of the iconographic repertoire, Le Corbusier resorted again to redrawing as in the case of Michelangelo’s St. Peter’s

19

See: Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 137.

: the church, placed on an ideal plan and completely abstracted from its context, is flanked on the right side by a section of the Colosseum. The graphic juxtaposition of the two buildings supports the dimensional comparison proposed in the image’s caption

20

Le Corbusier dimensionally compares St. Peter’s with Notre-Dame in Paris, St. Sophia in Constantinople and the Colosseum. Le Corbusier’s final thesis is that despite the mass, the coherence and spatial impact of Michelangelo’s dome, they were completely nullified by the extension of the nave by the architects who followed Michelangelo, in particular by Carlo Maderno. The visual comparison with the Colosseum is in any case inaccurate, as the height of the latter exceeds the façade of St. Peter’s by about ten metres.

, but also inevitably introduces a comparison, or association, of a formal and aesthetic nature. The character of plasticity, which Le Corbusier finds in Roman monuments as well as in Pirro Ligorio’s represented city, thus determines what is beautiful and what is ugly, or even what is architecture and what is not. In the Trois rappels, alongside a long survey of Canadian and American silos, Le Corbusier writes: ‘L’architecture égyptienne, grecque ou romaine est une architecture de prismes, cubes et cylindres, trièdres ou sphères : les Pyramides, le Temple de Louqsor, le Parthénon, le Colisée, la Villa Adriana. L’architecture gothique n’est pas, dans son fondement, à base de sphères, cônes et cylindres. […] C’est pour cela qu’une cathédrale n’est pas très belle et que nous y cherchons des compensations d’ordre subjectif, hors de la plastique. Les Pyramides, les Tours de Babylone, les Portes de Samarkand, le Parthénon, le Colisée, le Panthéon, le Pont du Gard, Sainte-Sophie de Constantinople, les mosquées de Stamboul, la Tour de Pise, les coupoles de Brunelleschi et de Michel-Ange, le Pont-Royal, les Invalides sont de l’architecture. La Gare du quai d’Orsay, le Grand Palais, ne sont pas de l’architecture.’

21

‘Egyptian, Greek or Roman architecture is an architecture of prisms, cubes and cylinders, trihedrons or spheres: the Pyramids, the Temple of Louqsor, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, the Villa Adriana. Gothic architecture is not based on spheres, cones and cylinders. […] That is why a cathedral is not beautiful and why we look for subjective compensations, outside the realm of plastic. The Pyramids, the Towers of Babylon, the Gates of Samarkand, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the Pont du Gard, Saint Sophia of Constantinople, the mosques of Stamboul, the Tower of Pisa, the domes of Brunelleschi and Michelangelo, the Pont-Royal, the Invalides are all architecture. The Gare du quai d’Orsay, the Grand Palais, are not architecture. ’Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 19. English translation by the author.

This is in turn a system of argumentation by visual comparison that closely resembles that of Pugin’s Parallels and Contrasts

22

See: A. W. N. Pugin, Contrasts. Or, A Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Middle Ages and Corresponding Buildings of the Present Day,London, Charles Dolman, 1836.

. Unlike the coeval architecture of Roman Renaissance, Michelangelo’s St. Peter’s is therefore beautiful in that it is as plastic and volumetric as the Roman imperial architecture, like the Colosseum that Le Corbusier placed alongside it. Although the representation is simpler and the comparison less systematic, the graphic operation is analogous to that carried out by John Soane with the comparative drawings for the lectures at the Royal Academy of Arts in the first decades of the 19th century, such as the one made by Charles Tyrell that depicts precisely the dome of St. Peter’s together with the Pantheon, the Radcliffe Library by James Gibbs and then the Rotunda of the Bank of England by John Soane himself

23

See: John Soane office, (1-10) RA Royal Academy Lecture Drawings of ancient and modern buildings showing their comparative sizes: Comparative drawing showing scales of St. Peter’s, the Pantheon, the Radcliffe Library and the Rotunda, Bank of England, c.1806-15, drawn by Charles Tyrell, reference number 23/2/2; and Comparative plans & elevations of Noah’s Ark and a Man of War, drawn by Henry Parke, reference number 23/2/10.

, or that of Henry Parke showing the comparison between a Noah’s Ark and a Man of War. With respect to the latter in particular, such an affinity is further demonstrated by the photographic collage included by Le Corbusier in the chapter Les Paquebots, with the dimensional comparison between the paquebot Aquitania, the façade of Notre-Dame de Paris, the tower Saint-Jacques, the triumphal arch and the opéra Garnier.

24

Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 71.

Ultimately, the discourse of Le Corbusier seems to be built on two main strategies of theoretical but also aesthetic and formal nature: the erasure of the urban fabric, and the objectification of the monumental building, with its definition in abstract plastic and volumetric terms.

The questioning of these ideas-images, the rediscovery of the urban fabric and the consequent reinsertion of architecture and of its compositional reasons, occupied architects throughout the course of the century and perhaps constituted the main theme with which the disciplinary discourse was confronted in the following decades. The basic materials of this gradual rediscovery remained essentially those adopted by Le Corbusier, namely the representations of the city and architecture of the past, particularly those of Rome. However, a different use of these same references, or tools, was to define a series of different if not opposing theoretical positions.

From the study of map by Le Corbusier/Pirro Ligorio, a further bridge to post-war theory seems to emerge: an unexpected opening to the analogous and picturesque composition of the collage city. This theme does not only emerge from the drawings but also from Le Corbusier’s words, words that reappear several times and that gradually take on a more explicit theoretical meaning: ‘Rome est un paysage pittoresque. La lumière y est si belle qu’elle ratifie tout. Rome est un bazar où l’on vend de tout.’

25

‘Rome is a picturesque landscape. The light is so beautiful that it ratifies everything. Rome is a bazaar where everything is sold.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 123. English translation by the author.

followed a few pages later by: ‘Rome est un bazar en plein vent, pittoresque.’

26

‘Rome is a picturesque, open-air bazaar.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 139. English translation by the author.

The city appears as a picturesque assemblage of autonomous fragments that only Roman light can illusorily hold together.

From this point of view, the inclusion of the Colosseum in the Borgo district already shows what will perhaps be the final consequence, the ultimate temporal perspective of Le Corbusier’s Roman vision, or at least its later interpretation: in a city of autonomous plastic volumes, it is form that eventually takes over, once the reasons of history fail. This is the same fate of imperial ruins. Starting with Piranesi and Pannini, the free assembly and reassembly of these ruins, obviously on the surface of the canvas, becomes the way to establish an otherwise impossible design contact with the city of the past. With their collages and photomontages, Colin Rowe, Aldo Rossi and the architects of Roma Interrotta fit precisely into this fracture of modernist rationality that has been present in the background since its inception.

The Model of Imperial Rome by Gismondi and the Collage City

From the outset, the theoretical reflection of Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter focuses on the figure of Le Corbusier, of which they attempt to offer an alternative reading, not based on explicit discourse, but directly on the works and in particular on their formal and visual affinities with a series of ancient references. 27 See in particular: C. Rowe, Le Corbusier: Utopian Architect [London 1959], in A. Caragonne (ed.), As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. I. Texas, Pre-Texas, Cambridge, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996, pp. 135-142, but also C. Rowe, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa, Mannerism and Modern Architecture, Neo-‘Classicism’ and Modern Architecture I, Neo-‘Classicism’ and Modern Architecture II, The Architecture of Utopia in C. Rowe, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1976. Even before writing Collage City, Rowe wanted to show the substantial continuity of modern architecture with the tradition of the past in order to broaden its horizons and thus identify new possible directions of development that would be capable of responding to the fundamental problems of post-war cities while preserving its original assumptions. From this point of view, Collage City seems to be precisely a close comparison with Vers une architecture and in particular a critical reinterpretation of its reading of ancient architecture, primarily Roman architecture, such as the imperial city and Hadrian’s Villa.

As Vers une architecture, Collage City is also an essentially visual kind of book, whose theoretical positions are mainly articulated through the choice and focused use of a substantial iconographic apparatus of images and drawings. In Collage City, perhaps even more consciously, the graphic ways in which these materials are composed on the page through their affinities, analogies and oppositions decisively influence the very structure of the text and the theoretical positions that emerge from it

28

The Swiss-German edition of the book, published in 1984 by Birkhäuser in collaboration with the Zurich gta and edited by Bernhard Hoesli with Monika Oswald, Christina Reble and Tobi Stöckli, is significant in that it proposes an expansion and revision of the iconographic apparatus that further emphasises and strengthens certain crucial aspects of the layout.

. This type of structure, of research and of visual communication, seems to be substantially grounded on Rowe’s experience at the Warburg Institute and on his familiarity with the iconological method of Aby Warburg, Erwin Panofsky and Rudolf Wittkower, with whom he developed his master’s thesis on the theoretical drawings of Inigo Jones in the late 1940s, just before moving to the United States.

In relation to this aspect, the initial sequence of the book appears significant in that it seems to visually anticipate, already within the first four pages, what will be the most important graphic and conceptual themes of the book, many of which are significantly linked to Roman architecture. Collage City thus opens with an evocative image of the Pantheon’s oculus, a figure to which Rowe and Koetter will return in the conclusion; followed by the title, flanked by a study of an ideal city by Francesco di Giorgio Martini and by Picasso’s Still Life with Straw Chair – in turn corresponding to the beginning and conclusion of the book – ; then by the contents, together with an image of the model of Imperial Rome from the Museum of Roman Civilisation (Fig. 3); and finally by David Griffin and Hans Kollhoff’s City of Composite Presence, the most emblematic representation of the collage city and, actually, its only formal prefiguration within the book.

03. Pages 156-57 from Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter, Collage City [1978], Basel, Boston and Berlin, Birkhäuser, 1984 © Birkhäuser Verlag

It is this formal aspect of relationship between the parts that, according to Rowe and Koetter, assumes the value of a political and philosophical metaphor of communal living within civil society and thus within the city itself, an open city in direct analogy with Karl Popper’s notion of open society, substantially plural and democratic. 29 See in particular: K. R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies. vol. I The Spell of Plato, and vol. II The High Tide of Prophecy: Hegel, Marx and the Aftermath, London, George Routledge & Sons, 1945. .

Popper’s theory probably also plays an important role in determining the relationship between the Roman and the Greek reference: the model of Rome is no longer placed side by side or superimposed upon that of Athens as a sort of further and subsequent development, but rather presented as an alternative. The former is the one that leads to the urbanism of the object, i.e. Le Corbusier’s one, the latter to that of the texture, i.e. the one of the traditional city and, consequently, the one of Collage City.

By Italo Gismondi, Rowe and Popper also include the 1937 model of Villa Adriana, which was in turn inspired by the earlier survey of the School of Engineers in the early twentieth-century. Similarly to Le Corbusier, Rowe and Koetter consider Villa Adriana as ‘miniature Rome’ 30 C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 94. , or as its synthetic abstraction beyond the real urban complexity. On the basis of this assumption, Hadrian’s Villa is visually and conceptually opposed to Versailles, as the symbolic forms of two opposing compositional paradigms, respectively polycentric and monocentric, which correspond in turn to two forms of thought but also of organisation and representation of urban political space 31 This comparison is visually even more evident in the Swiss-German edition edited by Hoesli, in which Versailles and Hadrian’s Villa are not placed on successive pages but on juxtaposed sides. .

The two central chapters of the book are therefore dedicated to the definition of the two fundamental graphic practices on which Rowe and Koetter would later build their idea of the collage city, or city of composite presence: the figure-ground, i.e. the empty-full graphic representation of the urban fabric, and the bricolage, i.e. the collage or assemblage of urban fragments. These two practices correspond in turn to two fundamental maps of the city of Rome that play a crucial role in the book, Bufalini’s sixteenth-century figure-ground that closely resembles Wayne Copper’s map of Wiesdbaden 32 Wayne Copper developed the figure-ground tool in 1967, as part of his thesis with Colin Rowe at Cornell University. The most emblematic representation of this method, that of the city of Wiesbaden, appears significantly on the cover of the original American edition of 1978. , with the compact centre in which the texture prevails and the surrounding countryside dotted with ruins, as autonomous objects in the landscape; and then Canina’s nineteenth-century model, which depicts instead the imperial city as a mere juxtaposition of monuments. This second model, which resonates with the contemporary project of the ‘city as museum’ conceived by Napoleon I for Paris, later realised by Leopold I and Leo Von Klenze for Biedermeier Munich, precisely evokes the fragmentary spatiality of Hadrian’s villa and thus in turn that of the City of Composite Presence.

In conclusion, the overlapping of these practices and references lead Rowe and Koetter to the recognition of the fundamental character that substantially determines the spatial configuration of the contemporary city. In a play of overlaps and reflections, this character is the relationship between interior and exterior, between public and private, but also, more generally, between the house and the city, or even between architecture and town planning, between their different scales and design methodologies:‘We think again of Hadrian. We think of the ‘private’ and diverse scene at Tivoli. At the same time we think of the Mausoleum (Castel Sant’Angelo) and the Pantheon in their metropolitan locations. And particularly we think of the Pantheon, of its oculus. Which may lead one to contemplate the publicity of necessarily singular intention (keeper of Empire) and the privacy of elaborate personal interests – a situation which is not at all like that of ville radieuse versus the Villa Stein at Garches.’ 33 C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 149.

While Le Corbusier, from a modern and object-oriented perspective, argues that: ‘Un édifice est comme une bulle de savon. Cette bulle est parfaite et harmonieuse si le souffle est bien réparti, bien réglé de l’intérieur. L’extérieur est le résultat d’un intérieur’

34

‘A building is like a soap bubble. This bubble is perfect and harmonious if the breath has been evenly distributed from the inside. The exterior is the result of an interior.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 146. English translation by the author.

, Rowe and Koetter propose a sort of substantial inversion: the interior, i.e. the architectural building, is first and foremost the result of the exterior, i.e. the public space of the city, exactly as in Bufalini’s representation of Rome, which, particularly in the matrix that appears in Collage City, seems to anticipate by about 200 years the more famous Nollimap, which is substantially based on this type of interpretation of urban space.

Through the model of Roman architecture, the modern paradigm of the complex house-simple city, the same principle on which the Loosian concept of urbanity is based, is thus radically challenged: on the one hand, the approach of typological analysis that has become widespread in these years allows for the greatest possible simplification of the urban texture and of related architectures, on the other hand, a new awareness of the city confronts the discipline with an ever-increasing level of urban complexity that must be addressed.

Rowe and Koetter are not, however, the only ones facing such issues in the post-war years. On the contrary, they are part of a broad international community that in those years reflected on the same problems and images on both sides of the ocean, producing in turn a series of key texts, see for example Edwin Bacon in America, but also of drawings and representations, with a more or less analytical or theoretical character, such as for example Saverio Muratori and Aldo Rossi with their surveys, Schwarzplan and città analoghe. 35 See for example: S. Muratori et al. (Centro Studi di Storia Urbanistica), Studi per una operante storia urbana di Roma, Roma, Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche, 1963, and E. N. Bacon, Design of Cities, New York, Viking Penguin, 1967. The topographical survey of the centre of Rome by Muratori, an urban plan in which the ground floors of the buildings are shown, a kind of extension of the Nollimap principle, certainly constitutes one of the main references in a series of similar representational experiments that would culminate in the topographical survey of the centre of Zurich by ETH students in 1974, the so-called Schwarzplan. As far as urban history and theory are concerned, already some ten years before Collage City, Edwin Bacon anticipated a study in some ways similar to that of Rowe and Koetter, also attempting a similar overlap between urban and artistic space through the works of Paul Klee. .

The Nollimap and the Portrait of a Fragmented Disciplinary Culture

04. Pages 2-3 from Architectural Design Vol. 49 No. 3-4, Roma Interrotta, 1979 © John Wiley & Sons Inc.

The theoretical project of the Collage City, only abstractly prefigured by the City of Composite Presence, found soon a further and more defined declination in Colin Rowe’s proposal for Roma Interrotta, the well-known exhibition organised by Piero Sartogo at the Mercati di Traiano in 1978 in which twelve architects were asked to work on the twelve folios of Giovanni Battista Nolli’s Nuova pianta di Roma of 1748 (Fig. 4). They were Piero Sartogo, Costantino Dardi, Antoine Grumbach, James Stirling, Paolo Portoghesi, Romaldo Giurgola, Robert Venturi and John Rauch, Colin Rowe, Michael Graves, Rob Krier, Aldo Rossi and Leon Krier.

Although the exhibition was held in the same year as the release of Rowe and Koetter’s book, it appears clear that the project is in fact its later development, or perhaps its ideal fulfilment. Together with Peter Carl, Judith Di Maio, and Steven Peterson, Rowe conceived a fictional reconstruction of the eighth sector of the Nollimap in which he imagined a possible past that never happened – a Napoleonic Rome inspired by the model of the ‘city as museum’. Such city seems in turn to be modelled on Canina’s coeval map of Rome included in Collage City, i.e. as a vast assemblage of monuments juxtaposed together in a composite manner.

From a graphic point of view, the operation carried out by Rowe’s group is essentially that of reuniting isolated objects, ruins or monuments by means of a new fabric of invention, giving them the value of emergencies, or stabilizers – as they are defined in the final excursus of Collage City –, within a large public field. This is exactly the practical and metaphorical reversal of the Lecorbusierian image of the city.

The Nolli plan, or just Nollimap, which was especially popular in post-war architecture and in particular in the United States 36 See: A. P. Latini, Nollimap in Mario Bevilacqua (ed.), Nolli Vasi Piranesi. Immagine Di Roma Antica e Moderna. Rappresentare e Conoscere La Metropoli Dei Lumi., Roma, Artemide edizioni, 2004, pp. 64-71. Significantly, the decision to use the Nollimap for Roma interrotta seems to have been made by Sartogo, who had previously been at Cornell where he had come into contact with Rowe and his Urban Design Studio. , performs here a dual function: on the one hand as a representation and thus as an ideal model of the city, and on the other hand as an object, by means of its very structure subdivided into twelve folios, which becomes precisely the physical support, the palimpsest for staging a disciplinary community and culture that is at least as fragmentary and composite as the same city of Rome.

Whether, as Rowe states, Roma Interrotta is configured as: ‘An interesting idea but one which could scarcely lead to any successful issue […]’ 37 C. Rowe, As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. III. Urbanistics, A. Caragonne, ed., Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996, p. 129. , also due to the very nature of most of the panels, which do not actually seem to offer substantial design challenges to be solved; and if therefore many contributions became mainly graphic exercises rather than real urban reflections, it is also true that the substantial transformation felt in the discipline towards the end of the Seventies seems to emerge clearly from this panorama. It is a crucial shift of scale and also of horizons. In this context, the representations of Rome that have accompanied twentieth-century theory from Le Corbusier to Rowe no longer serve as instruments of urban reflection, now perceived as impossible, but gradually became means for the transmission of an autonomous disciplinary content, first and foremost formal and aesthetic, architectural rather than urban, which uses the city as a metaphor and no longer as a real and possible objective.

It is in this context that one should read, for example, the contributions of Stirling and Rossi, who simply took up and inserted a series of their projects and realisations within the Roman landscape as the ultimate expression of the progressive autonomy and self-referentiality of the architect’s repertoire, i.e. ‘[…] the architect’s own working collection’ 38 C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 134. . If Venturi and Rauch emblematically do not intervene on the map but limit themselves to superimposing on it the sign of the Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, the new contemporary Rome from which it seems possible to learn a new approach to the dimension of the city; the interventions of Rob and especially Leon Krier, the most architectural ones, at least in appearance appear soon as impossible attempts to establish a contact with an antiquity now completely detached from the scope of the discipline. 39 This is exactly what was to emerge shortly afterwards with the 1980 Venice Biennale, La presenza del passato (The presence of the past), curated by Paolo Portoghesi.

1978 is also the year of the first publication of Delirious New York by Rem Koolhaas, in parallel with Collage City, the specular outcome of the coeval disciplinary debate at Cornell University

40

R. Koolhaas, Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, New York, Oxford University Press, 1978. Starting in 1972, Rem Koolhaas studied at Cornell University with Oswald Mathias Ungers, with whom he later collaborated on a series of crucial projects such as City in the City: Berlin, A Green Archipelago in 1977.

. Equally visual and just as connected to modern theoretical discourse, Delirious New York actually embodies the opposite urban model to Rowe and Koetter’s Collage City. Again speaking in Roman terms, this is precisely the model of the Castrum, the Roman ordering principle at its highest expression filtered through Anglo-Saxon and Northern European pragmatism, not surprisingly applied first to the colonies overseas. The New York grid, deprived of any utopian backdrop and becoming the ultimate expression of capitalistic liberalism, is indeed the epitome of the simple city-complex house principle of modernism. Perfectly self-regulated, the grid deprives the discipline of any possible control: the architect’s action can only be relegated to the dimension of the individual object, apparently freed from any constraint or restriction.

Henceforth, the spatial organization derived from this model seems indeed to clearly prevail over Rowe and Koetter’s composite city, which, however, persists as a disciplinary medium and thus, in accordance with Leroi-Gourhan’s definition, as a social and aesthetic instrument for the communities of practice which continue to recognize themselves in such a model.

If therefore Roma interrotta can be considered as the epilogue of a certain symbolic and formal trajectory of Roman representations, it was also in some ways a new beginning, at a different and parallel level. From being vectors of transatlantic exchange between major European and U.S. centers, the images of the exhibition began to widely spread at that time within a number of secondary local contexts such as for example Switzerland, Belgium, and Portugal, still marginal in cultural terms, but extremely dynamic and receptive.

The exhibition Composite Presence curated by Dirk Somers – Bovenbouw at the Belgian pavilion of 2021 Venice Biennale show precisely the effects of this second migration as well as of the complex superimposition of meanings that it managed to produce, thus giving rise to a new European and international disciplinary culture.

Bibliografia

G. C. Argan, C. Norberg-Schulz (eds.), Roma Interrotta, Roma, Officina edizioni, 1978.

E. N. Bacon, Design of Cities, New York, Viking Penguin, 1967.

R. Koolhaas, Delirious New York, New York, Oxford University Press, 1978.

M. M. Lamberti, Le Corbusier e l’Italia (1932-1936), in ‘Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia’, serie III, vol. 2, no. 2, , 1972, pp. 817-871.

A. P. Latini, Nollimap in Mario Bevilacqua (ed.), Nolli Vasi Piranesi. Immagine Di Roma Antica e Moderna. Rappresentare e Conoscere La Metropoli Dei Lumi., Roma, Artemide edizioni, 2004, pp. 64-71.

Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923.

A. Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech. Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1993.

B. Munari, Fotocronache, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Domus [Milano 1944], 1980.

S. Muratori et al. (Centro Studi di Storia Urbanistica), Studi per una operante storia urbana di Roma, Roma, Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche, 1963.

J. Petit, Le Corbusier : lui-même. Genève, Edition Rouseeau, 1970.

K. R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies. vol. I The Spell of Plato, and vol. II The High Tide of Prophecy: Hegel, Marx and the Aftermath, London, George Routledge & Sons, 1945.

C. Rowe, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1976.

C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978.

C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Basel, Boston, Berlin, Birkhäuser, 1984.

C. Rowe, As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. I. Texas, Pre-Texas, Cambridge, A. Caragonne, ed. Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996.

C. Rowe, As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. III. Urbanistics, A. Caragonne, ed., Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996.

G. C. Argan, C. Norberg-Schulz (eds.), Roma Interrotta, Roma, Officina edizioni, 1978.

- ‘The fotocronaca is a way of expressing oneself with images rather than words, images can be sculpted, drawn or photographed, the medium does not matter. Modern publishing urgency has turned the caveman’s chisel into a camera. Once upon a time, everyone had to go to Rome to learn about the history described on Trajan’s column. Today, that column has become a rotary press cylinder and the most distant reader can receive a copy at home.’ B. Munari, Fotocronache [1944], Milano, Corraini Edizioni, 1997, pp. 4-5. Author’s translation.

- A. Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, p. 401.

- S. Kubrick, director and producer, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968.

- The engraving used by Munari represents Leon Foucault’s demonstration of the pendulum in 1851.

- ‘THE WORD IS A SURROGATE FOR THE IMAGE.’ B. Munari, Fotocronache [1944], Milano, Corraini Edizioni, 1997), 6. Author’s translation.

- A. Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech…192.

- Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, pp. 161, 175.

- The reflection developed in the chapter was subsequently expanded by Le Corbusier with two articles published in the early 1930s in the journal Prélude, Esprit Grec – Esprit Latin – Esprit Gréco Latin and Rome, in which he addressed the theme of monumentality and of a “Mediterranean civilisation as the director of contemporary civilisation”. Prélude was ’the organ of an unspecified anti-parliamentary movement advocating Latin Europeanism’ of which Le Corbusier was one of four editors. See: M. M. Lamberti, Le Corbusier e l’Italia (1932-1936), in ‘Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia’, serie III, vol. 2, no. 2, , 1972, pp. 817-871.

- Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 106.

- Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 124.

- See:Italie Centrale. Rome et ses environs. Manuel du voyageur, Leipzig-Paris, Karl Baedeker, 1909.

- As is well-known, in the first decades of the century Le Corbusier undertook a series of journeys that would be fundamental to his training as an architect. From 1907 to 1923, the year of the publication of Vers une architecture, he was in Italy four times. He spent long periods in Rome, from where he visited Hadrian’s Villa and Pompeii, and profoundly grasped the substantial urban and landscape problems caused by the rapid expansion of the city in those years.

- ‘Ancient Rome was crushed within walls that were always too narrow; a city is not beautiful when it is crowded […] Everything in Rome is definitely too crowded’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 123. English translation by the author.

- M. M. Lamberti, Le Corbusier e l’Italia (1932-1936). Appendice B, in ‘Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia’, serie III, vol. 2, no. 2, 1972, pp. 860-861. All the documents included in the three Annexes to the text are preserved in the Archives of the Fondation Le Corbusier. In particular, the letter to Giuseppe Bottai is reproduced by Jean Petit, as the original cannot be found. See: J. Petit, Le Corbusier : lui-même, Genève, Edition Rouseeau, 1970, p.78.

- Concerning the progress in understanding and representing imperial Rome, see: A. P. Frutaz (ed.), Le piante di Roma, Roma : [s.n.], 1962. The maps of Rome prior to the Anteiquae Urbis Imago, even by Pirro Ligorio himself, mainly show the location of monuments without describing the fabric of the city. See in particular those by Domenico Gnoli based on the method of Leon Battista Alberti (1432-1434), by Piero del Massaio (1469), by Calvo and Egnazio (1527) and indeed by Pirro Ligorio (1553). This is a representative tradition that will persist in the following years, even if only occasionally. Thereafter, the general tendency will be to define in an increasingly precise and detailed manner the texture of the city’s minor fabric, the residential and productive fabric that fills the voids between the ruins, monuments and churches. In this regard, see for instance the maps by Stephen du Pérac (1574) and Mario Cartaro (1576 and 1979).

- ‘Outside Rome, with plenty of air, they have built the Villa Adriana. There they meditated on Roman greatness. There they gave order. It is the first great Western order.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 126. English translation by the author.

- In this regard, see in particular: E. N. Bacon, Design of Cities, New York, Viking Penguin, 1967, p. 216-217. Bacon refers in particular to the plan drawings from L’Architettura di Pietro .Giacomo Cataneo, published in Venice in 1567.

- See:E. Sellers Strong, Roman Sculptures from Augustus to Constantine, London, Gerald Duckworth and Company, 1911, p. 328.

- See: Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 137.

- Le Corbusier dimensionally compares St. Peter’s with Notre-Dame in Paris, St. Sophia in Constantinople and the Colosseum. Le Corbusier’s final thesis is that despite the mass, the coherence and spatial impact of Michelangelo’s dome, they were completely nullified by the extension of the nave by the architects who followed Michelangelo, in particular by Carlo Maderno. The visual comparison with the Colosseum is in any case inaccurate, as the height of the latter exceeds the façade of St. Peter’s by about ten metres.

- ‘Egyptian, Greek or Roman architecture is an architecture of prisms, cubes and cylinders, trihedrons or spheres: the Pyramids, the Temple of Louqsor, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, the Villa Adriana. Gothic architecture is not based on spheres, cones and cylinders. […] That is why a cathedral is not beautiful and why we look for subjective compensations, outside the realm of plastic. The Pyramids, the Towers of Babylon, the Gates of Samarkand, the Parthenon, the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the Pont du Gard, Saint Sophia of Constantinople, the mosques of Stamboul, the Tower of Pisa, the domes of Brunelleschi and Michelangelo, the Pont-Royal, the Invalides are all architecture. The Gare du quai d’Orsay, the Grand Palais, are not architecture. ’Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 19. English translation by the author.

- See: A. W. N. Pugin, Contrasts. Or, A Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Middle Ages and Corresponding Buildings of the Present Day,London, Charles Dolman, 1836.

- See: John Soane office, (1-10) RA Royal Academy Lecture Drawings of ancient and modern buildings showing their comparative sizes: Comparative drawing showing scales of St. Peter’s, the Pantheon, the Radcliffe Library and the Rotunda, Bank of England, c.1806-15, drawn by Charles Tyrell, reference number 23/2/2; and Comparative plans & elevations of Noah’s Ark and a Man of War, drawn by Henry Parke, reference number 23/2/10.

- Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 71.

- ‘Rome is a picturesque landscape. The light is so beautiful that it ratifies everything. Rome is a bazaar where everything is sold.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 123. English translation by the author.

- ‘Rome is a picturesque, open-air bazaar.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 139. English translation by the author.

- See in particular: C. Rowe, Le Corbusier: Utopian Architect [London 1959], in A. Caragonne (ed.), As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. I. Texas, Pre-Texas, Cambridge, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996, pp. 135-142, but also C. Rowe, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa, Mannerism and Modern Architecture, Neo-‘Classicism’ and Modern Architecture I, Neo-‘Classicism’ and Modern Architecture II, The Architecture of Utopia in C. Rowe, The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1976.

- The Swiss-German edition of the book, published in 1984 by Birkhäuser in collaboration with the Zurich gta and edited by Bernhard Hoesli with Monika Oswald, Christina Reble and Tobi Stöckli, is significant in that it proposes an expansion and revision of the iconographic apparatus that further emphasises and strengthens certain crucial aspects of the layout.

- See in particular: K. R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies. vol. I The Spell of Plato, and vol. II The High Tide of Prophecy: Hegel, Marx and the Aftermath, London, George Routledge & Sons, 1945.

- C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 94.

- This comparison is visually even more evident in the Swiss-German edition edited by Hoesli, in which Versailles and Hadrian’s Villa are not placed on successive pages but on juxtaposed sides.

- Wayne Copper developed the figure-ground tool in 1967, as part of his thesis with Colin Rowe at Cornell University. The most emblematic representation of this method, that of the city of Wiesbaden, appears significantly on the cover of the original American edition of 1978.

- C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 149.

- ‘A building is like a soap bubble. This bubble is perfect and harmonious if the breath has been evenly distributed from the inside. The exterior is the result of an interior.’ Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture, Paris, Éditions Crès, Collection de ‘L’Esprit Nouveau’, 1923, p. 146. English translation by the author.

- See for example: S. Muratori et al. (Centro Studi di Storia Urbanistica), Studi per una operante storia urbana di Roma, Roma, Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche, 1963, and E. N. Bacon, Design of Cities, New York, Viking Penguin, 1967. The topographical survey of the centre of Rome by Muratori, an urban plan in which the ground floors of the buildings are shown, a kind of extension of the Nollimap principle, certainly constitutes one of the main references in a series of similar representational experiments that would culminate in the topographical survey of the centre of Zurich by ETH students in 1974, the so-called Schwarzplan. As far as urban history and theory are concerned, already some ten years before Collage City, Edwin Bacon anticipated a study in some ways similar to that of Rowe and Koetter, also attempting a similar overlap between urban and artistic space through the works of Paul Klee.

- See: A. P. Latini, Nollimap in Mario Bevilacqua (ed.), Nolli Vasi Piranesi. Immagine Di Roma Antica e Moderna. Rappresentare e Conoscere La Metropoli Dei Lumi., Roma, Artemide edizioni, 2004, pp. 64-71. Significantly, the decision to use the Nollimap for Roma interrotta seems to have been made by Sartogo, who had previously been at Cornell where he had come into contact with Rowe and his Urban Design Studio.

- C. Rowe, As I Was Saying. Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays. Vol. III. Urbanistics, A. Caragonne, ed., Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1996, p. 129.

- C. Rowe, F. Koetter, Collage City, Cambridge and London, The MIT Press, 1978, p. 134.

- This is exactly what was to emerge shortly afterwards with the 1980 Venice Biennale, La presenza del passato (The presence of the past), curated by Paolo Portoghesi.

- R. Koolhaas, Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, New York, Oxford University Press, 1978. Starting in 1972, Rem Koolhaas studied at Cornell University with Oswald Mathias Ungers, with whom he later collaborated on a series of crucial projects such as City in the City: Berlin, A Green Archipelago in 1977.