Return to archive

title

Revealing the tacit: a critical spatial practice based on walking and re/presenting

Author

Nilsu Altunok

Abstract

Spatial practices that investigate architectural space with the ideal architect's eye and a commonplace representational perspective have been the subject of a lot of writing. The potential of critical spatial practices, which combine performative actions with incomplete representation possibilities, to investigate and reveal the tacit knowledge underlying space is yet unexplored. This paper finds its problem in these missing pieces in the literature and tries to decipher by deconstructing the conventional methods and tactics it criticizes, a way is sought to trigger the creative potentials of the relationship between body and space that cannot be stable. Critical spatial practices can be situated as alternative ways of understanding the architectural space and establishing a dialogue with it since they pave the way for new kinds of relationships to emerge between the subject and the space. This study focuses on the act of walking, which is claimed to be a critical spatial practice, and its re/presentation, which is argued to reveal tacit knowledge in the walked place. Based on the poststructuralist critical theories, the case study was carried out in the Historical Peninsula of Istanbul in the Khans District by walking and extracting the things which can reveal tacit knowledge. By finding top-down investigation and representation tools problematic in capturing and expressing the body and space interactions, experiences, and experimentation on the ground level, I believe walking by drifting through the invisible spaces and transitions of the Khans District when viewed from above is meaningful in expressing the experimental and creative flows on the ground level. Depending on the re/presentation, it can be suggested that performing a spatial practice with the participation of the body and interpreting the architectural space from a critical position carry the contingency of uncovering tacit knowledge.

Introduction

Much has been written about spatial practices that explore architectural space with the eye of an ideal architect who holds a conventional representation approach. What has not been written enough yet is the potential of critical spatial practices that assemble performative acts and unfinished representation possibilities to explore and unveil the tacit knowledge behind space. This dichotomy is both a speculation on a tenor that I believe is missing in the literature and an expression of my intention in this study in the context of tacit knowledge

1

This study was produced from the thesis that I was carrying out under the supervision of my advisor, Prof. Dr. Pelin Dursun Cebi, in the Architectural Design Graduate Program of Istanbul Technical University. In the context of tacit knowledge, I would like to express that the paper contributed by opening a new gap in the flow of the thesis.

. The tinder of this paper’s present debate is conventional architectural perception and representation concepts dating back to the Renaissance’s vision that investigates the city with a prioritized elevated eye.

When the elevated eye is embodied in the oblique image, the direction of the view is both downwards and lateral.

2

Mark Dorrian, “The aerial view: notes for a cultural history,” Strates, no. 13 (December 2007): 3.

Such oblique images which can be described as the Renaissance’s view of the city are the views that started to be represented in the early 16th century and looks at the city in a panoramic way (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Map of Florence attributed to Francesco Roselli, 1473. URL-1 URL-1: https://www.e-skop.com/skopbulten/modern-siyasetin-gozu-niccol%C3%B2-machiavellinin-tuhaf-perspektifi/5881 access date: 16.03.2023

Figure 1 Map of Florence attributed to Francesco Roselli, 1473.

3

“Modern Siyasetin Gozu: Niccolò Machiavelli’nin Tuhaf Perspektifi,” E-skop, accessed March 16, 2023, https://www.e-skop.com/skopbulten/modern-siyasetin-gozu-niccol%C3%B2-machiavellinin-tuhaf-perspektifi/5881.

Although these images, whose source is a hill, a castle, or a tower overlooking the city, were produced to be a holistic record, they distanced themselves from the city and became a simulacrum of it. Moreover, when various aircraft gained dominance there was no need for a tower, a hill, or a castle to reach an elevated eye, vertical images started to be produced. These images recorded further away from the city or landscape visualize a “new perception and experience of landscape hitherto unknown” according to Bernd Hüppauf.

4

Bernd Hüppauf as cited in Dorrian, “The aerial view,” 10.

In this paper, I hypothesize that understanding and illustrating the city from vertical images with the birds-eye view was failing to capture experientiality and accurate scale of perception.

Questioning The Eye That Looks from Above

Although there is no significant connection to say that the orthographic and perspectival views evolve with the cultural history of the aerial view, it has similar shortcomings to the aerial view. Adrian Forty criticizes these drawings as they “require viewers to imagine themselves atomized into a thousand beings suspended in space before the building; and perspectival drawings, conversely, expect the viewer to suppose they are one-eyed and motionless in one spot”.

5

Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 40.

This kind of approach dictates the distance between the observer and the observed object to a particular measure and reckons without considering that different observers could have different gazes and experiences.

The approach of investigating the city with a top-down view has been continuing with modernity. In his authoritative La Production de l’éspace, initially published in 1974, Henri Lefebvre referred to a crucial moment of a certain space pulverization that took place around 1910.

6

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 25.

With the crucial moment mentioned, Euclidean and perspectivist spaces have disappeared with other forms of references.

7

Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 25.

Situating a Critical Spatial Practice

At this juncture, to reject uniform and pre-constituted architectural representation typologies, this paper aims to propose a way to experience and represent the place in another way. To achieve this goal, I am positioned between architecture and the critical theory of force. Based on the post-structuralist critical theories, I chase to trigger the potential of creativity of the body and space relationship in the context of critical spatial practices and find the walking concept en route.

Critical spatial practices can be situated as alternative ways of understanding the architectural space and establishing a dialogue with it since they pave the way for new kinds of relationships to emerge between the subject and the space. Jane Rendell unfolds critical spatial practices; as practices that go beyond the boundaries of art and architecture, try to explore interdisciplinary processes and practices, emphasizing the importance of not only the critical but also the spatial, immanent with the social and aesthetic, the public and the private, the inside and the outside.

8

Jane Rendell, Art and Architecture: A Place Between (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2006), 6-8.

In this respect, it is possible to say that critical spatial practices are mediating surfaces that allow and even provide an environment for a two-way relationship between theory and practice.

Starting from this point of view, this study focuses on the act of walking, which is claimed to be a critical spatial practice, and its re/presentation, which is argued to reveal tacit knowledge in the walked place. My background and position as a researcher are important as they influence my experience and knowledge and stitch my subjective seams between explicit and tacit knowledge. The subjective view, which sets out to decipher the embedded information about the place, is also in place in this sense.

Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula

On the morning of Thursday, March 23, 2023, I awake to the sight of overcast skies enveloping Istanbul. Despite the cloudy conditions, my intuition assures me that no rain will interrupt me. Before setting off, I anticipate that my critical spatial practice will sew new kinds of relationships between my body and space, allow for interchangeable situations between theory and practice, and reveal tacit knowledge on the ground being walked. With this intuition, I turn my direction towards the Historical Peninsula to initiate the walk. The Historical Peninsula bears witness to the overlapping narratives, the interplay of diverse influences, and the intricate entanglement of history, creating a palimpsest that invites exploration and interpretation.

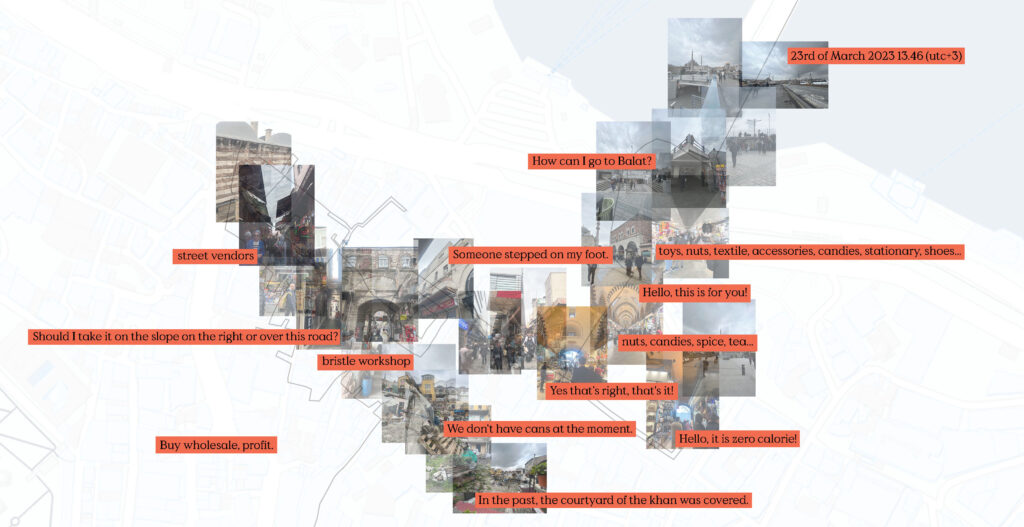

Since this paper criticizes the view from above, I decide to walk around Eminönü, Khans District, in a place the movement and flow at the ground level differ, the orientation of the walking body changes depending on the ground, and the walkers can establish various kinds of relations with their environment. However, there neither is a predetermined direction, destination, or pace nor a map, site plan, or satellite image accompanying the walk. Standing on my feet upon the Galata Bridge, I look in the direction of the Historical Peninsula, and with a subjective conscious, I get my first toehold in real space. I am the walker, recorder, and researcher of the walk yet I am not a passive observer. I engage in the walk with my whole body and my consciousness, so that my body acts like a catalyst that transforms the walked place as I trace. I record the walk with frequently taken photographs and audio recordings. The audio recordings become the fleeting sections of my walk. In these fleeting sections, I noted the unexpected encounters, the spatial differentiations, the conversations of the people around me, my conversations with other people, interesting events, the way my body was oriented, and the passages I encountered while walking on the ground floor, alleys, or dead ends. I care about recording the walk in-situ since I believe the record –no matter what medium– will provide a reinterpretation of the walk after taking a certain distance from it and even, the recording can initiate a critical re/presentation process of the walk.

I am walking along the Galata Bridge. I have nowhere to reach at the end of the walk. I am just on the move. I know that to pass to Eminönü, I must utilize the designated underpass, the sole passage allocated for pedestrians. It serves as the essential conduit, allowing the walking body to traverse from one side to the other, connecting the distinct realms of experience embodied by each side of the underpass. Indeed, the designated underpass is not only transit but also becomes a space where diverse happenings occur. Whilst passing this space, I think of how other people and the space interact with me. It is a realm where the city’s bustling energy converges and we encounter fellow walkers. That is when someone stops me. Why did she stop? What would she say? This person in the hustle and bustle of the city asked me how to get to Balat in a hurry.

I must use a second underpass after the first one to cross the street. Here I see items for sale: watches, glasses, toys that make noise and move, nuts, candies, stationery, jewelry, bags, shoes, umbrellas, textiles, and many more… When I got to the ground from the underpass, my body moved towards the entrance of the Spice Bazaar standing in front of me. I choose to go in. I realize that some of the products sold in the bazaar were similar to those sold in the underpass: teas, spices, candies, jewelry… As soon as the vendors see me coming, they come out of the many shops lined up with their trays and treats on them. I hear, “Hello, this is for you” in English. Another says, “Yes, that’s right! That’s right there” even though I never asked him. Why are these people trying to invite me to the shop with their trays in their hands? I am just walking.

I continue to walk in the Spice Bazaar trying to discover the openings that can leak me out. It has more than one door and I choose the Hasırcılar door to exit. All the vendors on the ground level of the buildings on the right and left, extend their eaves and awnings of different sizes and colors over the street. Am I indoors or am I outdoors? It gets blurry. These eaves, which are constantly converging and moving away from each other, are starting to be creepy on one hand, because they draw a limited, constantly blurring veil between what is seen from above and what is experienced at the ground level, on the other hand, it creates sudden changes in perspective, multiplying my personal experience. During these sudden shifts in perspective, my feet are discovering a wide variety of dead ends and passages. I do not know if these are marked on the map. It is as if Hasırcılar Street is a spine, an axis, or an alley, there are many passages around it, streets that progress and end abruptly, and there are inns with a courtyard where relations become complicated.

In this walk, I have autonomy in my orientation, speed, and more. However, I realize that I cannot have full autonomy. While situating myself as a critical walker, recorder, and researcher, I also described myself as a catalyst that continuously changed the space that I traced. Chemical catalysts are substances that do not change their own structure while increasing the rate of the reaction they enter. However, as I walk under the eaves, in the passages I enter and exit, I transform. The walk becomes an ideal vehicle for my personality formation and learning through my body. At this juncture, I remember Judith Butler’s performativity concept.

9

Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988).

Whilst walking I am not a passive observer of the designated cultural or spatial codes, rather I play my own role and invigorate interpretations of the walked place within the boundaries of existing directives.

10

Butler, “Performative Acts,” 526.

How do I exactly learn through my body? I get confused (Fig. 2).

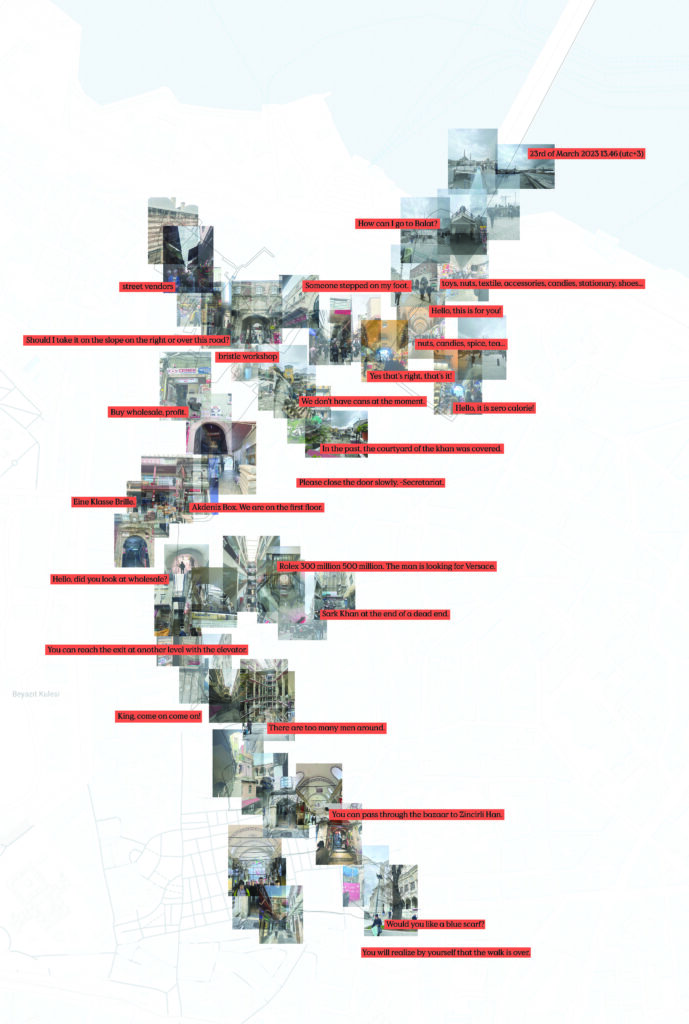

Fig. 2 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

Figure 2 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

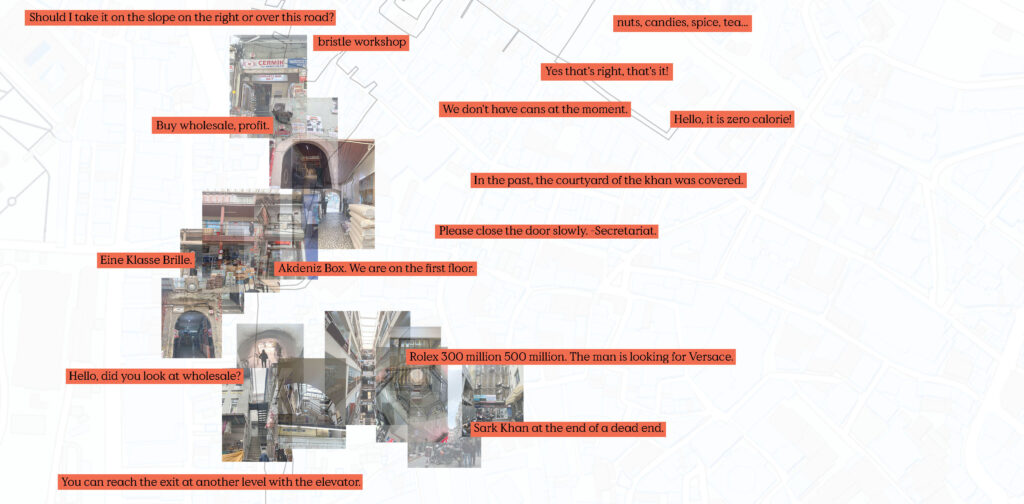

Looking at the building on my left through the gaps I find through the eaves of the stores along this street, I realize that this building may be a khan with repeated arches in its structure. Where can I understand? I am an architect, and it is felt even from the outside that there can be a courtyard in the middle of the building, and if it is, following the entrance of this khan through the periphery of the building, I start searching. While swirling around, I find the entrance to the khan. This is Balkapanı Han. The Balkapanı Han, which I know is somewhere around here, but surprised to come across it. I was right to think that there was a courtyard in the middle of the building around which I walked, but when I step into the courtyard, I encounter completely different spatial situations. The atmosphere in the courtyard of the khan is quite different from that in the outer perimeter. Stored items, unused spaces, and structural additions to the original structure cause the space to offer a layered experience in every sense.

As I am walking in the courtyard of the Balkapanı Han, a sense of urgency compels me to swiftly convey the sights and sounds that unfold before me. The space envelops me as an autonomous producer of my affections and relations. Unique and context-specific circumstances prompt me to draw comparisons and encounter juxtapositions, creating an interplay of ideas and perceptions. I find myself engaged in a conversation with a man named Yavuz, who emerges from one of the shops within the courtyard. Curiously, he asks about my purpose there, whether I am photographing or seeking to meet Mr. Halil from the triathlon federation. To my surprise, he expresses a desire to introduce me to Mr. Halil. Intrigued by his proposition, I accept and venture inside. Meeting Mr. Halil provides me with valuable insights into the history of the courtyard. I learn that it had previously been covered, serving as a gathering place for merchants trading food items such as honey and molasses, and their customers. The echoes of this past social and spatial interaction seem to linger in the courtyard, subtly revealing their presence. My experience of exploring Balkapanı Han has served as a significant clue in unveiling a situated knowledge through my bodily movement. With each step I take, each interaction I encounter, and each observation I make…

I step out of the door of Balkapanı Han. I pass the narrow passage between two buildings that stand so close to each other and find myself in a small square. The fluidity of direction concepts and the unexpected transitions that arise in this space adds to its intriguing nature. It is a place where paths intersect, where different trajectories converge, and where the unexpected becomes a part of everyday life. My experience is both bodily and cultural, totally through movement and walking. My subjective interpretation of the city unfolds like a feminist objectivity which is mentioned by Donna Haraway (1988). She says, feminist objectivity cares about situated knowledge of a limited location not separating subject and object (Haraway, 1988). In my direct experience, my vision gains privilege instead of a view from above. A more situated and positioned vision tries to define another kind of knowledge gaining, totally through movement and walking. I walk through Uzun Çarşı Street, and a new urban experiencer emerges. The act of walking becomes a vehicle for knowledge acquisition.

I walk, as I walk, I discover spatial stories on the ground level, some of them obvious and some of them tacit. I am on a street lined with various khans on the right and left side by side. Like a library, each shelf of which is separated according to its subjects, the khans here are also separated according to their subjects. Technological tools here, accessories and watches here, toys here, winter clothes here, hijab clothing here… I am entering one. “This is exclusively a wholesale establishment.” I am going out. There is another inn right in front of it: Paçacı Han. The previous one was Selamet Han. I listen to the requests of those who enter and leave the shops other than me, “Eine klasse Brille!”. Pausing intermittently, I reflect, reminisce, leaving traces of my presence and recounting my experiences through my own subjective lens. Tamburacı Han, Görenli Han—names whispered in passing. “Hello there, were you seeking wholesale goods?” No, my gaze extends beyond mere transactions; I am walking all the way (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

Figure 3 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

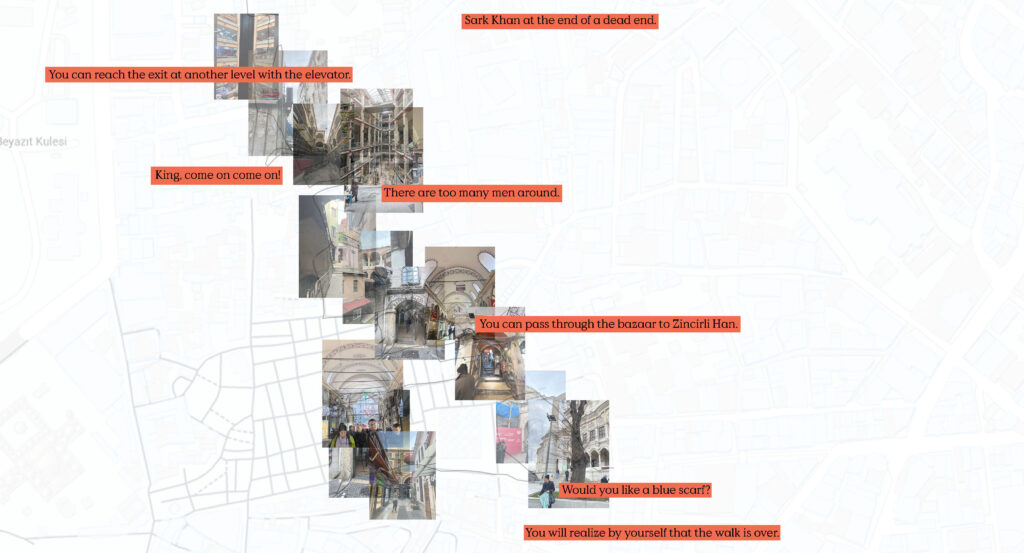

I found myself stepping into Tahtakale Vakıfhan. Countless signs, shops around a long, thin gallery space… My movement from Vakıfhan leads me to Asri Han, and from there, I make my way to Yıldız Han. Each of these spaces boasts a unique gallery space and a network of stairs that facilitate movement across different floors. These gallery spaces and staircases present manifold possibilities for vertical displacement. However, the most striking and inevitable encounter lies ahead at Şark Han, resonating with the rhythmic sounds of iron forging—knock, knock, knock! I find myself compelled to confront it, for Şark Han stands as the ultimate destination on this street, with its relationship with the topography, leaving me with no alternative but to pass through it. To move further, I must venture into the Şark Han, traversing through the Tahtakale gate. Ascending two floors via the vertical circulation apparatus linked to the gallery space, I eventually emerge through the Mercan exit. This complex vertical progression becomes a prerequisite should I desire to continue my walk beyond this point (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

Figure 4 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

So, I exit. I walk, as I walk, I find myself traversing a different topographical level. I suddenly find myself within the expanse of the Grand Bazaar, and subsequently, in Zincirli Han. The Grand Bazaar grows increasingly intricate as I progress, resembling a labyrinth where intersecting streets from all directions intertwine and converge. The intertwining becomes a complex knot, forcing me to weave through it, skirting around its corners, continuously altering my pace, ultimately leading me to exit through the Nuruosmaniye Gate. At this moment, I realize that my walk has come to a spontaneous conclusion. Upon reaching Nuruosmaniye, I am suddenly approached by men holding blue drapes. What was their intent? Could it be an attempt to conceal the influential cartography I had traced with my physical presence? I do not know. (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

Figure 5 Re/presentation of the Critical Walking Experience in the Historical Peninsula (belongs to the author).

In Lieu of Conclusion

With this walking experience, I went on a journey on the ground level of the city with the absolute effect of my personal knowledge as a researcher and urban walker. Throughout this journey, I have been involved in many spatial, social, and economic relations with the participation of my whole body, regarding a place that I cannot see or acquire by looking at the map. From this aspect, walking as a critical spatial practice carry the contingency of uncovering tacit knowledge about the walked place. The representation, which is a rewriting of the walk, expresses a production that would be possible in different mediums that different walkers could apply to express or record their walking experiences. Trying to raise speculation to uncover tacit knowledge, this paper offered a critical suggestion that is based on walking and re/presenting.

REFERENCES

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988): 519–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

Dorrian, Mark. “The aerial view: notes for a cultural history.” Strates, no. 13 (December 2007): 1-17.https://doi.org/10.4000/strates.5573

E-skop. “Modern Siyasetin Gözü: Niccolò Machiavelli’nin Tuhaf Perspektifi.” Accessed March 16, 2023. https://www.e-skop.com/skopbulten/modern-siyasetin-gozu-niccol%C3%B2-machiavellinin-tuhaf-perspektifi/5881.

Forty, Adrian. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

Rendell, Jane. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. New York: I. B. Tauris, 2006.

- This study was produced from the thesis that I was carrying out under the supervision of my advisor, Prof. Dr. Pelin Dursun Cebi, in the Architectural Design Graduate Program of Istanbul Technical University. In the context of tacit knowledge, I would like to express that the paper contributed by opening a new gap in the flow of the thesis.

- Mark Dorrian, “The aerial view: notes for a cultural history,” Strates, no. 13 (December 2007): 3.

- “Modern Siyasetin Gozu: Niccolò Machiavelli’nin Tuhaf Perspektifi,” E-skop, accessed March 16, 2023, https://www.e-skop.com/skopbulten/modern-siyasetin-gozu-niccol%C3%B2-machiavellinin-tuhaf-perspektifi/5881.

- Bernd Hüppauf as cited in Dorrian, “The aerial view,” 10.

- Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 40.

- Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 25.

- Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 25.

- Jane Rendell, Art and Architecture: A Place Between (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2006), 6-8.

- Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988).

- Butler, “Performative Acts,” 526.