Return to archive

title

Traveling Perspectives: Tracing ‘impressions’ of a project in Flanders

Author

Caendia Wijnbelt

Abstract

The collection of localities that play an active (and overlooked) or quiescent (yet potent) role in architectural practices are put in question here. The chapter investigates how a project and its site specific geographical setting can contain traces of broader architectural contexts. It asks how architectural collaborative approaches that stem from the encounter of different perspectives can be read in the lived environment through the lens of plurilocality. Distinct yet intermingling perspectives of a contemporary architectural realisation are drawn out through a dive into the meeting and convention centre in Bruges. This is a building designed by two offices based in different architectural environments — the Portuguese practice Souto de Moura Arquitectos alongside the Antwerp-based firm META architectuurbureau. Various perspectives of the same building are set in parallel, exploring place through similarities and differences. From different modes of apprehending the project, concepts of place and architectural intentions set in motion in this instance are unpacked, involving a transversal reading through a broader architectural community of practice. Active instances of getting to know a place through experience can thereby be tacit yet situated: they can be embodied, embedded and enacted. This further explores Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s hint of a depth found in the latent form of impressions, in their ‘caché-révélé’ or hidden-revealed. Expressions of such instances, through interpreting reflexive features of buildings that stem from plurilocal collaborations, become productive insights into the mechanisms of place relation, their transfers and interweaving, and their impact in architectural design practices. Most of all, these parcels of the tacit dimension of place interpretation are put forward as such: aggregates that interfere with- and feed a relation-full practice of living environments.

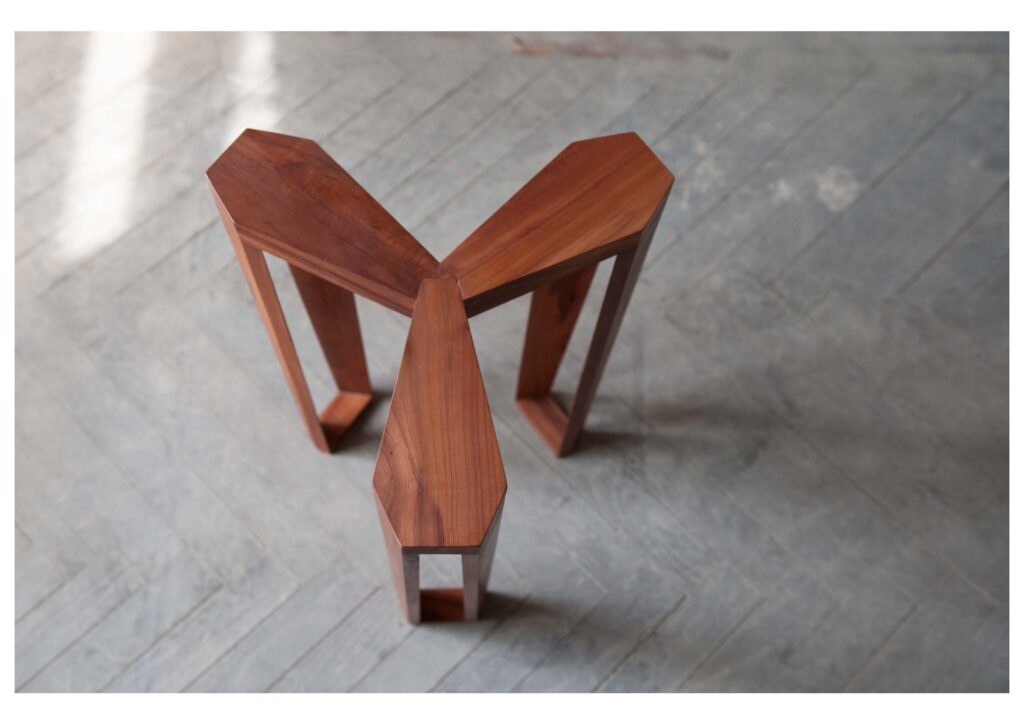

Figure 6.1: Detail on the Belvedere of the BMCC, photographed February 2022.

This column (Fig. 6.1) is one of twenty-five monumentally vertical presences in front of a glass façade that spans four floors. The photo, taken on site during a field study, depicts the upper level of the Bruges Meeting and Convention Centre (2021) designed by Souto de Moura Arquitectos — a Portuguese practice — in collaboration with a local Belgian office, META Architectuurbureau. 1 META Architectuurbureau, “Bruges Meeting & Convention Centre,” accessed July 2, 2022, https://meta.be/nl/projecten/bruges-meeting-convention-centre; Francesco Dal Co, et al., eds., Souto de Moura. Memory, Projects, Works (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019). Leaning on transdisciplinary concepts and specific photographical techniques as interpretative tools and lenses, this essay interweaves different perspectives of the BMCC project by encouraging plural perspectives for prehension of place in architectural practices.

Figure 6.2: Focus on the front façade of the BMCC. Photographed December 2022.

The plurilocal as potential

Active instances of getting to know a place often relate to individually experienced situations that enter the realm of tacit knowing. When approaching sites and localities, architectural practitioners seek to grasp the surroundings they are dealing with. This can involve an array of activities and tools, from the more obvious site-visiting, sketching, or modelling, to active recalling of past experiences, knowledges, and affinities. Collaborations between several offices, as instances where such site explorations and involvements take on all the more importance, are one of many forms of collaborative work in architecture. Architectural theorist Dana Cuff, in particular, in her book, Architecture: The Story of Practice (1991), describes the negotiations and mediations that are involved in more collective endeavours, in tension with the idea of architectural qualities stemming from singular or limited authorships. 2 Dana Cuff, Architecture: The Story of Practice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991), 73. Suggesting on the contrary many differently weighted voices and perspectives, the multilocal can reference the embeddedness of several localities in a singular place — the interwoven nature of sites when interpreted through collaborations. A multilocal collaboration can be understood as both a collaborative stance having multiple local centres of attention, and as a way of working that stems from several localities with a focus on a single place. In fields such as geography, anthropology, and urban planning, multilocality is increasingly a key concept in socio-spatial research, concerned with movements between places through notions such as mobility or migration. 3 Peter Weichhart, “Multilokalität – Konzepte, Theoriebezüge und Forschungsfragen,” Informationen zur Raumentwicklung 1/2 (2009): 1–14.

In the early 1990s, anthropologist Margaret Critchlow widened this path of understanding in her essay, ‘Empowering Place: Multilocality and Multivocality’ (1992). 4 Margaret Critchlow, “Empowering Place: Multilocality and Multivocality,” American Anthropologist n.s. 94, no. 3 (September 1992): 640–56, esp. 649. She advocates thinking of place through the lens of multilocality. Critchlow proposes a multilocal way of seeing, where dislocation can lead to greater awareness of contrasts between the known and the unknown: ‘seeing a new landscape in terms of a familiar one’. 5 Ibid., 652. At the scale of a single site, multilocality ‘shapes and expresses the polysemic meanings of place for different users’, thereby taking into account the spectrum of different, individual experiences that relate to the site. 6 Ibid. 647. Multilocal as a term is representative of such contexts that deal with a broad spectrum of places, often at a larger scale than what is in focus for architectural conception. Thinking about architectural processes in a similar way may result in a slightly revisited terminology, implying the relation between several sites instead of multitudes. Thereby, plurilocal attitudes could be suggestive of layered and multivalued apprehensions of the localities involved in architecture. They encompass both individual (yet composed of several focuses) and collaborative approaches (thereby relating to various points of view) that further the design process by generating mental and physical matter to work with in documentative, descriptive, or analytical phases.

As a main actor of the BMCC project design that is the focus of this research, the Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura highlights a topic that often surfaces when practitioners are asked to reflect on their own approaches to plural localities. 7 Tatiana Bilbao, speaking in Louisiana Channel, “Empathy is a superpower in architecture: 10 architects share their advice,” YouTube, June 10, 2021, video, 14:16, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_5GvFRDgFQ. See also Barbara Begoni and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Learning from History, Designing into History (Matosinhos: AMAG, 2020), 38. As he suggests, lived and travelled places — which feed into individual bodies of knowing and experience — play a role in design processes. He describes his mentor, the architect Fernando Távora, as having taught him the value of varied life experiences as grounding for his architectural approach: ‘the more you live, travel, the more you get to know people, things or materials, the better architecture can be made’. 8 Katharina Francesca Lutz, Haltung. Bewahren: Fernando Távora, Eduardo Souto de Moura und ihr Umgang met Denkmalen (Vienna: TU Wien, 2020), 136. This implies the active use of frames of reference when conceiving projects that moreover grow with encountered situations and are focused through iterative experience, becoming more specific. Through these remarks, plural places are put forward as influential when apprehending new contexts, albeit rarely being discussed. Not tackled however is how places, as influences, are considered and moreover put to use while conceiving and perceiving projects. The French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu discerns specific approaches that weave together different modes of thought and open up a broader encompassing of such contexts within objects of focus: thinking more relationally may be sparked as an intention, yet does not assume that each relation is intentional or easily pinned down. Instead, it supposes an openness to a wider array of factors and influences, and intentional attitudes towards their expression in different forms. 9 Pierre Bourdieu, “Thinking Relationally,” in An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, ed. Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 224–35. See also Margitta Buchert, “Intentions. Intensities,” in Intentions of Reflexive Design, ed. Buchert (Berlin: Jovis 2021), 27. This encourages reflexive modes of research that acknowledge more precise, but also less obvious, layers of understanding that play a role while not being explicit.

Figure 6.3: BMCC, photographed February 2022

Can experiential tools for qualitative, deepened site apprehension be enhanced and made actionable more intentionally in architectural conception and reading processes, bringing into focus reflexive capacities of perceivers? The BMCC (Fig. 6.2–3), combining a convention space on its upper levels with a vast exhibition hall on the ground floor, is a project located on the Beursplein of Western Bruges (Fig. 6.4), realised through a ‘design and build’ competition modality at the request of the city, that is rooted in such influences. 10 Hera Van Sande, “Pragmatisch, puur en poëtisch,” in “Reimagining the Office,” special issue, A+ Architecture in Belgium 295 (April–May 2022): 26. Through its design team constellation, involving parties from several contexts, it can become an opportunity to go beyond common understandings of referencing other locales to find useful, iterated modes of operating in plurilocal processes of making place and reading it by interpretation. What follows is a series of four short interpretative pathways for the Beursplein project, and its relation to plural localities and contexts. The field study involved multiple avenues of research, stemming from a variety of locally-driven experiences:

-

Figure 6.4: Western Bruges from above. The BMCC is situated nearest to the canal. Sketched June 2022.

Two site visits to the Congresgebouw: one with META architect Pietter Lansens and an editorial member of the fifteenth Flanders Architectural Review, Petrus Kemme (04.02.2022); a second one of several days deepening these initial impressions by different analytical approaches.

- Participation in a lecture, given by Souto de Moura, in Lisbon at the Autonomous University. 11 Eduardo Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade, por Eduardo Souto de Moura” (lecture, Conferência integrada no Ciclo de conferências do doutoramento em Arquitetura Contemporânea Da/UAL 2022, Autonomous University, Lisbon, April 6, 2022).

- A transcribed discussion (17.11.22) with the same editorial member, reflecting on the site visit according to our memories of different perspectives, and also approaching the topic of a second lecture given by Souto de Moura to a broader audience in Bruges. 12 Eduardo Souto de Moura, “Echoes of architectural tradition: Eduardo Souto de Moura (P): a passionate life’s work” (lecture, BMCC, Bruges, April 23, 2022).

Engaging various context

The topics of frames of reference, different locally-embedded viewpoints, and plural ways of reading place came up early in these avenues of research, and can begin to be explored through the backgrounds of both firms. Founded in 1992, META architectuurbureau — the local architects in this collaboration — is led by two partners who currently work with a conception team of eleven people. 13 META Architectuurbureau, “Team,” accessed July 2, 2022, www.meta.be/nl/profiel/team. Over the years, the practice has become known for their pragmatic approach using structural repetitions or gridded formal structures, where masonry often becomes the malleable infills they work with. Furthermore, they use materials widely used across the local context of this project.

Figure 6.5: Guided Site visit by Pietter Lansens (META) with Petrus Kemme (VAi) in the context of the Flanders Architectural Review 15, Bruges. Photographed February 2022.

Regarding bricks, for example, the Flanders yearbook editor highlights the expression ‘Belgie is geboren met en backsteen in de maag’ (Belgium is born with a brick in its stomach), meaning that all wish to build their own houses. Highlighting at once both the dilemma of the overpowering number of small-scale projects in a small country, and the fate or legacy of bricks in the Flanders architectural scene, such small rastered materials are intimately linked to individual housing. In most contemporary projects in Flanders, including works by META, the bricks, proportional to the scale of the building, become structuring spatial elements. Challenged through the size of the BMCC, they are additionally associated with a texture. 14 Ethnographic response, Petrus Kemme, Antwerp, Belgium (17.11.22) As communicated during the guided site visit (Fig. 6.5), the façades were no surrender to the context but, rather, an initiative to echo the surrounding neighbourhood while at the same time affording something very different and revised. For META, the shape and almost contradictory materiality to the scale of the project are a play on structure and rhythm often found in their projects. 15 Ethnographic response, Pietter Lansens, Bruges, Belgium (04.02.22)

On the other hand, Eduardo Souto de Moura, lead designer for the Beursplein project, concedes his lack of contact with brick up to that point, a material rarely found in the Portuguese scene. 16 Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.” Actively realising works in the Portuguese context since the early 1980s with the help of his office collaborators, he instead compares the learning curve of conceiving with bricks for the first time to the knowledge needed for a similarly common material in Portugal: tiles. His metro project in Porto for example, finished in 2005 — one of his major projects among larger scale interventions within a city infrastructure — uses white tiles enveloping most of the Bolhão entrance building’s upper mass. This envelope becomes a way to embed and relate the strong lines and size of the new station within the densely-knit urban fabric. During the Lisbon lecture, he reflected on the difficulties encountered then, and described the BMCC as a chance to study and get to know this way of doing, with the assistance of META and the firms on the ground. This example, for Souto de Moura, represents an adaptation of a way of thinking about locally-embedded approaches, transferring from one context to another, as well as an understanding of the weight of local know-how, often present in the architect’s work. 17 See, for instance, Werner Blaser, Eduardo Souto de Moura: Stein Element Stone (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003), 17, 27, 39. This can be seen in other areas of the BMCC project, where, for instance, the awareness of working with a parcel of historical, UNESCO World Heritage-driven Bruges is witnessed. The overall form and ground-level porosity of the building to the Beursplein, in contrast to the majority of the smaller, more detailed surroundings, seems thought out as a balance between standing out and shaping continuities with the silhouette of the city, especially through the textured façades that appear almost eroded.

Figure 6.6: View of the historical centre of Bruges from the Belvedere of the BMCC, photographed February 2022.

Anchoring to the locality

Souto de Moura described the difference in context between Portugal and Belgium as being at the root of such an approach, almost as if imposed by the surroundings. Rather than seeking an exterior aspect that would bring more rigidity or uniformity to the building, entitling his talk “Leveza e Gravidade” (lightness and gravity), he described how, in this case, the bricks should look like they have been there forever. 18 Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.” To do so, he encouraged the opposite of a regularity: ‘pedi para ser a fingir que era antigo queria tijolos de demolições’ (I asked to feint that [the building] was old; I wanted demolition bricks). The reuse of an old material, however, was not feasible due to sheer amount required, availability, and cost. 19 Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.” The architect compared this with the use of concrete: too planned or too tight, and it becomes pretentious, he suggests. The pseudo-historicity he hoped for the project was in part focused, in the end, on the mode of laying the bricks. The team asked the builders if they could use a more traditional way of laying them in mortar (fully placed in the mortar, ‘met trowel afgestreken en niet meer gevocht’, or ‘spread with a trowel, and left alone’). 20 Liesbeth Verhulst, host, “BMCC Brugge: nieuwe landmark met kleurenpalet van de stad,” Architectura podcast, July 2, 2022, accessed November 11, 2022, www.architectura.be/nl/podcasts/bmcc-brugge-nieuwe-landmark-met-kleurenpalet-van-de-stad/. Through these variations, the kind of ‘gravity’ that Souto de Moura wanted to work with was an imperfect one that could integrate dimensions of time. A reflexive attitude can be read in his approach when he makes obvious the intention of dealing with a certain depth of time: with the characteristics of Bruges as a historic city (Fig. 6.6) with many remainders of its old parcellation. In this courtyard-model medieval city — complete with old bridges, houses, and churches in natural stone — one finds a kind of patina that Souto de Moura wishes to bring into the conception of the project, affecting its relation to this area of the city. Such underlying intentions within the design process, which features multivalent understandings of site and locality while taking in deepened design processes of interpretation, can start to define reflexive moments. 21 Margitta Buchert, Landscape-ness as Architectural Idea (Berlin: Jovis, 2022), 308

Tools and modes of operation

In these different pathways of interpretation, the interest lies beyond singular or collaborative creative authorship, although this could help to question how such collaborations generate a shift between different points of view, design ideas, orientations, and localities. Collaborations involving several places are, like other mediative stances, rooted in back-and-forths, or negotiations, between people, ideas, and understandings. 22 Klaske Havik, Urban Literacy: Reading and Writing Architecture (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2014), 24 In this regard, such collaborative projects are also plurivocal. Souto de Moura’s utterance in his first meetings with META, as reported in the Flanders Architectural Review — ‘On parle la même langue’ (we speak the same language) — expresses a kind of synchronicity that took place during the collaborative processes behind the Beursplein conception. 23 Hülya Ertas, “Bruges Meeting and Convention Center,” in Flanders Architectural Review 15, ed. Sofie de Caigny, Bijdragen van Livia de Bethune, Maarten Desmet, and Hülya Ertas (Antwerp: Flanders Architecture Institute, 2022), 167. Collaborations are built on dialogue, which META describes as having being very present on-site in the conception phase of the project. Such dialogue may not in first place refer to spoken and written exchanges: the collaborating members relied on exchanging in their non-primary languages, switching between English and French. This further suggests that speech and writing were only a background element of the ‘language’ the architect could be referring to. They may have instead found a guiding thread in the exchange of media, through architectural design processes. From Souto de Moura’s side, sketches became amain means for exploring ideas and guiding concepts within the collaboration, as they would be communicated to META in each discussion. For their part, the team at META worked to a large extent through models, evolving and sharing them with each new exchange between the two offices. 24 Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.” The internationally configured team was confronted with different modalities for conceiving ideas, which seeped into the gradual construction of their concepts by generating a common ‘language’ — as Souto de Moura hinted at — through different respective tools, attitudes, and ways of working for the project.

Figure 6.7: Analogue double exposures. The BMCC overlayed with the Beursplein neighbourhood, photographed December 2022.

Superimposing as research modus

Overlays, until now of processes, can also be productive visualisation research tools that spark other points of view within the direct surroundings of the Congresgebouw, which can be enhanced through photographic modalities of research. As discussed, in a city like Bruges, where everything is small and structured with a lot of detail and ornament, the BMCC can be felt as a strong urban mass that stands out from its context. This is explored through double exposures (Fig. 6.7) highlighting visual and perceptual contrasts that happen while experiencing the Beursplein: encountered neighbourhood details merge with street-level views of the project and user-driven activities happening on site. The first diptych interweaves views of more intimate-scaled urban moments with the extroverted main square. One can interpret such moments as meeting points that provoke mental comparisons that routinely happen on-site, influencing how the square is visited or passed through. Layering different sculpted rooflines of the neighbourhood with interactive moments around the project (Fig. 6.8) highlights similar contrasts, yet also depicts different urban presences of these small projects in relation to the BMCC. The ancient housing that populates Western Bruges, with its detailed textures and ornaments, showcases how the project takes on a less familiar stance through the vast, partially blind upper mass, and the reflective surfaces on ground level that act as a sounding board to the surrounding street activities.

Figure 6.8: Analogue double exposure. Historical Bruges rooflines meet the BMCC, photographed December 2022.

Figure 6.9: Analogue double exposure. Between tension and harmony, two street scenes meet. Photographed December 2022.

This kind of simultaneous standing out and standing back is reinforced through (Fig. 6.9), where although the depth of the façade and its differentiation from the architectural surroundings is still visible, the images mostly shed light on dwellers and passers-by, something that the building is shaped to promote, enhancing its role as part of the main public buildings of Bruges. In this instance, overlays are used as a modality of place prehension, whereby investing into perceived similarities and differences of a newly encountered local becomes key to sparking reflexive modes of thought: they open more grounds of place perception by deliberate intertwining of different contexts. What unavoidably happens subconsciously when engaging with new environments can then be directed more intentionally. 25 Caendia Wijnbelt, “Double Exposing Place,” in Repository: 49 Methods and Assignments for Writing Urban Places, ed. Carlos Machado e Moura, Dalia Milián Bernal, Esteban Restrepo Restrepo, and Klaske Havik, 62–65. (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2023). In this sense, each photograph is read as an exploration of impressions, as overlays of place.

Contexts of place interpretation

Contexts that shape horizons of understanding around the Congresgebouw collaboration in Bruges are enactive and layered. They include the backgrounds of respective formations, the cultural realm these actors are immersed in, their past collaborations and experiences, and the specific time in which the project took place. These are not limited to the geographical or national settings the architects would ‘belong’ to. Traces of these contexts can be found in specified or interpreted geographical influences. In these contexts — which can be projected or guessed, but not pinned-down — one thereby finds blurred lines. Through his chapter in the book, Intentions of Reflexive Design (2021), Portuguese architect and professor Ricardo Carvalho suggests that there are crossovers in the architectural realm of intentions and that architectural responses to the built environment are related to broader architecturally-specific understandings, often stemming from lineages of common referential attitudes, common bodies of knowing that are collaboratively built. 26 Ricardo Carvalho, “Uncertainty, Criticism, Architecture,” in Intentions of Reflexive Design, ed. Buchert, 92–94; Buchert, “Intentions. Intensities,” 26; Buchert, “Formation and transformation of place,” in Simply design: Ways of Shaping Architecture, ed. Laura Kienbaum and Buchert (Berlin: Jovis, 2013), 69. In this and other perspectives — such as those put forward through critical regionalism — a balance between global influences and local specificities is discussed: how local attitudes stem from responses to a place regardless of their origin. 27 Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Post-Modern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Washington: Bay Press, 1983), 16–30. As a know-how and ability that feeds off a wide range of influences, site-conceptualisation and apprehension is then rooted in shared (and more or less individually sharpened) attentiveness and sensibilities to existing surroundings. Different views open up sensory qualities of sites to a wider realm of understanding that hints at common modalities and composite, diversified architectural communities of practice, influenced by classical modernity and its revisions. In this setting, the act of shaping interpretations of a locality, as a productive modality in architecture, is at the same time the shaping of a kind of world (or rather plurilocal) discourse relating to place that plays an implicit yet active (and enactive) role. This plurilocal discourse on place interpretation thereby simmers down a much wider and more abstract multilocal one found in other fields. It particularly relates to practices in contemporary architecture in light of experience and interpretation mostly taking place — for the situational contexts of this chapter — in a broader European spectrum. In post-colonial contexts, the plurilocal could open up other perspectives. These lean on repositories of places or place experiences, and act as a lens through which one can fathom a particular place that could be fruitfully triggered in architecture for designing in relation to encountered situations through reflexive moments.

Figure 6.9: ‘Horizons’ and situations of perception. Sketched April 2023.

A palimpsest of perceptual driving forces acts as lens by which one can fathom a particular site, a particular lens out of many. Already at the beginning of the twentieth century, the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl discussed an approach to perception and interpretation that involves preceding experience when he says: ‘[to] every perception there always belongs a horizon of the past, as a potentiality of awakenable recollections; and to every recollection there belongs, as a horizon, the continuous intervening intentionality of possible recollections (to be actualized on my initiative, actively), up to the actual Now of perception’. 28 Edmond Husserl, Cartesian Meditations (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1962), 40, 44–45. Although Husserl first approaches layers of perception through the lens of unrealised possibilities, he also ties to these possibilities the many past experiences that could be ignited through each active perceptual instance. As a horizon — or as a lens — these overlays can be understood as an added dimension through which perceiving and interpreting situations takes place. If directed back to the sites and localities that are experienced in architectural practices, this highlights an embedded thickness to perception that is useful in the design process. This thickness (Fig. 6.9) can be intentionally explored, and thereby be characterised as reflexive approach. On the other hand, it can also remain unexplored potential, creating a disconnect with what is actively shared and mediated throughout architectural practice. This highlights the need for a different kind of attentiveness and expression in order even to be discussed.

Figure 6.10: ‘Impressions’ and sensations brought to the surface. Sketched April 2023.

Reflexive approaches in reading and creating place can enhance such horizons. The philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, in his Notes de cours (1959–1961), further discusses an idea of depth behind the visible, or behind what is in focus, that can be reconnected to conceptualising tacit knowing in architecture, specifically in the context of perceiving and interpreting place. 29 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Notes de cours 1959–1961 (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 167–68. Depth, and its usefulness for stating the entangled relations between the visible world and lived experience, are at the core of this work, as well as his other posthumously published manuscript, The Visible and the Invisible (1964). In the former, he relates to what J. Gasquet has written about Cezanne’s work, describing depth as something that is brought into the world by sensations, but that goes beyond them, to their root, as the hidden revealed. 30 Ibid., 167. Sensations, in his French use of the word, are also understood beyond the stimulated senses to describe the ‘impressions’ that play a role in recognising and asserting the lived environment. These traces, as he suggests, can be in the fold of the visible. 31 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible (Paris: Gallimard, 1964), 222, 244, 270–77. Rather than expressing subjective perspectives, ‘impressions’ designate some perceptions that go beyond the underlying, that are brought to the surface — into focus — thereby receiving a more noticeable form of thought (Fig. 6.10). Through his approach to perceptions and lived experience, Merleau-Ponty highlights a latency that takes the shape of marks — or traces — left behind on our sensations. 32 Ibid., 167. This could characterise knowledges that are implicit by being embodied, embedded, and enacted, and by being active (and overlooked) or quiescent (yet potent) in architectural prehension of place.

These become productive in interpretative situations, and influence the depth of experiences of, and relations to, place. Research and design with reflexive dimensions could promote ways of doing and attitudes that emphasise awareness of traveling perspectives, and find new approaches to make these perspectival travels more intentional and productive. Mindful travels in the conception phases of architecture are not literal displacements and emplacements, but reflexive approaches that help to shape new ideas. Through the reception and experience of architecture, they act as invested and intentionally ‘tinted’ ways of perceiving and interpreting the built environment, with more breadth and awareness of plural perspectives, also features of reflexive approaches. Displacing and emplacing stances are active in underpinning ways when generating impressions and shaping perspectives. Reflexive shifts — shaped by dynamic mediating attitudes in design actions that encompass manyfold, versatile modes of thought — play a role in bringing these movements to a productive surface. 33 Margitta Buchert, preface to Reflexive Design, 10–12.

Figure 6.11: The auditorium curtain-wall referencing Mies van der Rohe. Guided Site visit by Pietter Lansens (META) with Petrus Kemme (VAi) in the context of the Flanders Architectural Review 15. Bruges, photographed February 2022.

Back in Lisbon, as Souto de Moura approached the end of his lecture segment on the Bruges Congresgebouw, he displayed a photograph of the giant curtain-wall (Fig. 6.11) that divides the auditorium from the entrance terrace with a view of the city. As he unveiled the image, he stated: ‘These frames: I was “desperate” so I made a citation — not a reference. I went to Mies[van der Rohe], those [window frames from the house he designed] in 1933: and “pumba”! Identical; you can [go and] see for yourself’. 34 Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade”: ‘E depois isto abre para um terraço. Estes caixilhos — estava desesperado então é uma citação, não é homenagem, fui ao Mies [van der Rohe], tais da ‘33, e “pumba!”. Igualzinho. Podes mostrar.’ Translation by Eren Gazioglu, emphasis my own. NB ‘Pumba’ could be read as ‘and voilà’. What he describes makes obvious the presence of a spectrum of ways in which apprehending place also stems from perceived impressions of other places. His ‘citation’ is a clear instance of having grounded his approach through another locality. At the same time, through referencing Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, it embeds the blurred lines of a metaphor of the global through common grounds in modern and contemporary architecture and communities of practice, perhaps concerned with a plurilocal discourse of place impressions. Further, in tracing pathways of interpretation through the example of the Beursplein project, the opposite end of the spectrum is suggested: instances where these influences remain underlying yet guiding to the architectural approaches to the site at hand. Then — whether relations between several places can be pin-pointed and understood or only vaguely guessed — a plurilocal way of thinking and working is a dynamically evolving tool, that can be sharpened through qualitative experiences, in the same way that knowledges involved in place-prehension are. The foregoing exercise placing different perspectives of a project hints at a tacit knowledge that is not enclosed, but rather acts as a placeholder to delimit a variety of reflexive opportunities, as instances that promote going beyond existing environments and frames of thought, which can be found within plurilocal modes of thought.

The power of latent knowledges

Experimenting with impressions of place, I wonder how far the notion of tacit knowledge, when taken as such from other fields that lean on social theories, opens up new insights for place related architectural design. 35 See, for instance, Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), and Harry Collins, Tacit & Explicit Knowledge(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). The ideas of tacit or implicit highlight a value (being silent, hidden, displaced, obscured, or invisible to the perceiver), added to the concept of knowledge that is already a complex, non-material one. The prompt of the tacit, to the researcher (–practitioner) seems, in my view, to be the urge for its revealing. Instead, through a reflexive research practice that puts in focus the plurilocal, I find it productive to consider these parcels of knowing as latent. The latent or even imminent — two terms that Merleau-Ponty uses often in his late manuscript to replace his idea of what is simply hidden beneath our awareness — could be a fruitful lens for researching embodied, embedded, and enacted knowing in architecture. 36 Merleau-Ponty, Notes de cours, 167–68; Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible. With no need to reveal a perceived invisible, the latent anticipates its unfolding, or even more so: it is already progressing towards realisation. Then, the hint would be that a sentient being’s challenge is to enact, take action, activate. 37 Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, “A New Naturalism (7 micromanifestos),” 2G 22 (May 2003): 26–33. Rather than disengaging by understanding the tacit from a bird’s-eye-view, this would call for attunement to reflexive possibilities. Rather than taking on a fixed form, latent knowledges would be on the move. 38 Margitta Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move,” in The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research, ed. Lara Schrijver (Leuven:Leuven University Press, 2021), 41–51. Traveling, changing, evolving, and not necessarily placed; they are expectant. In this way, they are helpful shifts in perspective for understanding plurilocal approaches in architecture as resources to be revalued through practice, whether in academic, office-driven, or cultural realms. To conclude with the topic of reflexive shifts in perspective in relation to places: perceptual traces can move between processes, people, and situations, or between the experienced, the known or remembered, and the anticipated. Most of all, they participate in engagements with place that can help shape an increasingly vital form of plurilocal empathy and are there for the taking.

Bibliography

- Ábalos, Iñaki, and Juan Herreros. “A New Naturalism (7 micromanifestos).” 2G 22 (May 2003): 26–33.

- Begoni, Barbara, and Eduardo Souto de Moura. Learning from History, Designing into History. Matosinhos: AMAG, 2020.

- Blaser, Werner. Eduardo Souto de Moura: Stein Element Stone. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. “Thinking Relationally.” In An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, edited by Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant, 224–35. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Buchert, Margitta. “Design Knowledges on the Move.” In The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research, edited by Lara Schrijver, 41–51. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021.

- Buchert, Margitta. “Formation and transformation of place.” In Simply design: Ways of Shaping Architecture, edited by Laura Kienbaum and Buchert, 35–65. Berlin: Jovis, 2013.

- Buchert, Margitta. “Intentions. Intensities.” In Intentions of Reflexive Design, edited by Buchert, 14–39. Berlin: Jovis 2021.

- Buchert, Margitta. Landscape-ness as Architectural Idea. Berlin: Jovis, 2022.

- Carvalho, Ricardo. “Uncertainty, Criticism, Architecture.” In Intentions of Reflexive Design, edited by Margitta Buchert, 92–94. Berlin: Jovis, 2021.

- Collins, Harry. Tacit & Explicit Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Critchlow, Margaret. “Empowering Place: Multilocality and Multivocality.” American Anthropologist n.s. 94, no. 3 (September 1992): 640–56.

- Cuff, Dana. Architecture: The Story of Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

- Dal Co, Francesco, et al., eds. Souto de Moura. Memory, Projects, Works. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

de Moura, Eduardo Souto. “Echoes of architectural tradition: Eduardo Souto de Moura (P): a passionate life’s work.” Lecture, BMCC, Bruges, April 23, 2022.

de Moura, Eduardo Souto. “Leveza e gravidade, por Eduardo Souto de Moura.” Lecture, Conferência integrada no Ciclo de conferências do doutoramento em Arquitetura Contemporânea Da/UAL 2022, Autonomous University, Lisbon, April 6, 2022. - Ertas, Hülya. “Bruges Meeting and Convention Center.” In Flanders Architectural Review 15, edited by Sofie de Caigny, Bijdragen van Livia de Bethune, Maarten Desmet, and Hülya Ertas, 165–172. Antwerp: Flanders Architecture Institute, 2022.

- Frampton, Kenneth. “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance.” In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Post-Modern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, 16–30. Washington: Bay Press, 1983.

- Havik, Klaske. Urban Literacy: Reading and Writing Architecture. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2014.

- Husserl, Edmond. Cartesian Meditations. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1962.

- Lutz, Katharina Francesca. Haltung. Bewahren: Fernando Távora, Eduardo Souto de Moura und ihr Umgang met Denkmalen. Vienna: TU Wien, 2020.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Le Visible et l’Invisible. Paris: Gallimard, 1964.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Notes de cours 1959–1961. Paris: Gallimard, 1996.

- META Architectuurbureau. “Bruges Meeting & Convention Centre.” Accessed July 2, 2022. https://meta.be/nl/projecten/bruges-meeting-convention-centre.

- META Architectuurbureau. “Team.” Accessed July 2, 2022. www.meta.be/nl/profiel/team.

- Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Van Sande, Hera. “Pragmatisch, puur en poëtisch.” In “Reimagining the Office.” Special issue, A+ Architecture in Belgium 295 (April–May 2022): 26–30.

- Verhulst, Liesbeth, host. “BMCC Brugge: nieuwe landmark met kleurenpalet van de stad.” Architectura podcast. July 2, 2022. Accessed November 11, 2022. www.architectura.be/nl/podcasts/bmcc-brugge-nieuwe-landmark-met-kleurenpalet-van-de-stad/.

- Weichhart, Peter. “Multilokalität – Konzepte, Theoriebezüge und Forschungsfragen.” Informationen zur Raumentwicklung 1/2 (2009): 1–14.

- Wijnbelt, Caendia. “Double Exposing Place.” In Repository: 49 Methods and Assignments for Writing Urban Places, edited by Carlos Machado e Moura, Dalia Milián Bernal, Esteban Restrepo Restrepo, and Klaske Havik, 62–65. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2023.

- META Architectuurbureau, “Bruges Meeting & Convention Centre,” accessed July 2, 2022, https://meta.be/nl/projecten/bruges-meeting-convention-centre; Francesco Dal Co, et al., eds., Souto de Moura. Memory, Projects, Works (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

- Dana Cuff, Architecture: The Story of Practice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991), 73.

- Peter Weichhart, “Multilokalität – Konzepte, Theoriebezüge und Forschungsfragen,” Informationen zur Raumentwicklung 1/2 (2009): 1–14.

- Margaret Critchlow, “Empowering Place: Multilocality and Multivocality,” American Anthropologist n.s. 94, no. 3 (September 1992): 640–56, esp. 649.

- Ibid., 652.

- Ibid. 647.

- Tatiana Bilbao, speaking in Louisiana Channel, “Empathy is a superpower in architecture: 10 architects share their advice,” YouTube, June 10, 2021, video, 14:16, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_5GvFRDgFQ. See also Barbara Begoni and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Learning from History, Designing into History (Matosinhos: AMAG, 2020), 38.

- Katharina Francesca Lutz, Haltung. Bewahren: Fernando Távora, Eduardo Souto de Moura und ihr Umgang met Denkmalen (Vienna: TU Wien, 2020), 136.

- Pierre Bourdieu, “Thinking Relationally,” in An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, ed. Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 224–35. See also Margitta Buchert, “Intentions. Intensities,” in Intentions of Reflexive Design, ed. Buchert (Berlin: Jovis 2021), 27.

- Hera Van Sande, “Pragmatisch, puur en poëtisch,” in “Reimagining the Office,” special issue, A+ Architecture in Belgium 295 (April–May 2022): 26.

- Eduardo Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade, por Eduardo Souto de Moura” (lecture, Conferência integrada no Ciclo de conferências do doutoramento em Arquitetura Contemporânea Da/UAL 2022, Autonomous University, Lisbon, April 6, 2022).

- Eduardo Souto de Moura, “Echoes of architectural tradition: Eduardo Souto de Moura (P): a passionate life’s work” (lecture, BMCC, Bruges, April 23, 2022).

- META Architectuurbureau, “Team,” accessed July 2, 2022, www.meta.be/nl/profiel/team.

- Ethnographic response, Petrus Kemme, Antwerp, Belgium (17.11.22)

- Ethnographic response, Pietter Lansens, Bruges, Belgium (04.02.22)

- Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.”

- See, for instance, Werner Blaser, Eduardo Souto de Moura: Stein Element Stone (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2003), 17, 27, 39.

- Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.”

- Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.”

- Liesbeth Verhulst, host, “BMCC Brugge: nieuwe landmark met kleurenpalet van de stad,” Architectura podcast, July 2, 2022, accessed November 11, 2022, www.architectura.be/nl/podcasts/bmcc-brugge-nieuwe-landmark-met-kleurenpalet-van-de-stad/.

- Margitta Buchert, Landscape-ness as Architectural Idea (Berlin: Jovis, 2022), 308

- Klaske Havik, Urban Literacy: Reading and Writing Architecture (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2014), 24

- Hülya Ertas, “Bruges Meeting and Convention Center,” in Flanders Architectural Review 15, ed. Sofie de Caigny, Bijdragen van Livia de Bethune, Maarten Desmet, and Hülya Ertas (Antwerp: Flanders Architecture Institute, 2022), 167.

- Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade.”

- Caendia Wijnbelt, “Double Exposing Place,” in Repository: 49 Methods and Assignments for Writing Urban Places, ed. Carlos Machado e Moura, Dalia Milián Bernal, Esteban Restrepo Restrepo, and Klaske Havik, 62–65. (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2023).

- Ricardo Carvalho, “Uncertainty, Criticism, Architecture,” in Intentions of Reflexive Design, ed. Buchert, 92–94; Buchert, “Intentions. Intensities,” 26; Buchert, “Formation and transformation of place,” in Simply design: Ways of Shaping Architecture, ed. Laura Kienbaum and Buchert (Berlin: Jovis, 2013), 69.

- Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Post-Modern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Washington: Bay Press, 1983), 16–30.

- Edmond Husserl, Cartesian Meditations (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1962), 40, 44–45.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Notes de cours 1959–1961 (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 167–68.

- Ibid., 167.

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible (Paris: Gallimard, 1964), 222, 244, 270–77.

- Ibid., 167.

- Margitta Buchert, preface to Reflexive Design, 10–12.

- Souto de Moura, “Leveza e gravidade”: ‘E depois isto abre para um terraço. Estes caixilhos — estava desesperado então é uma citação, não é homenagem, fui ao Mies [van der Rohe], tais da ‘33, e “pumba!”. Igualzinho. Podes mostrar.’ Translation by Eren Gazioglu, emphasis my own. NB ‘Pumba’ could be read as ‘and voilà’.

- See, for instance, Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), and Harry Collins, Tacit & Explicit Knowledge(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Merleau-Ponty, Notes de cours, 167–68; Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible.

- Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, “A New Naturalism (7 micromanifestos),” 2G 22 (May 2003): 26–33.

- Margitta Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move,” in The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research, ed. Lara Schrijver (Leuven:Leuven University Press, 2021), 41–51.