Return to archive

title

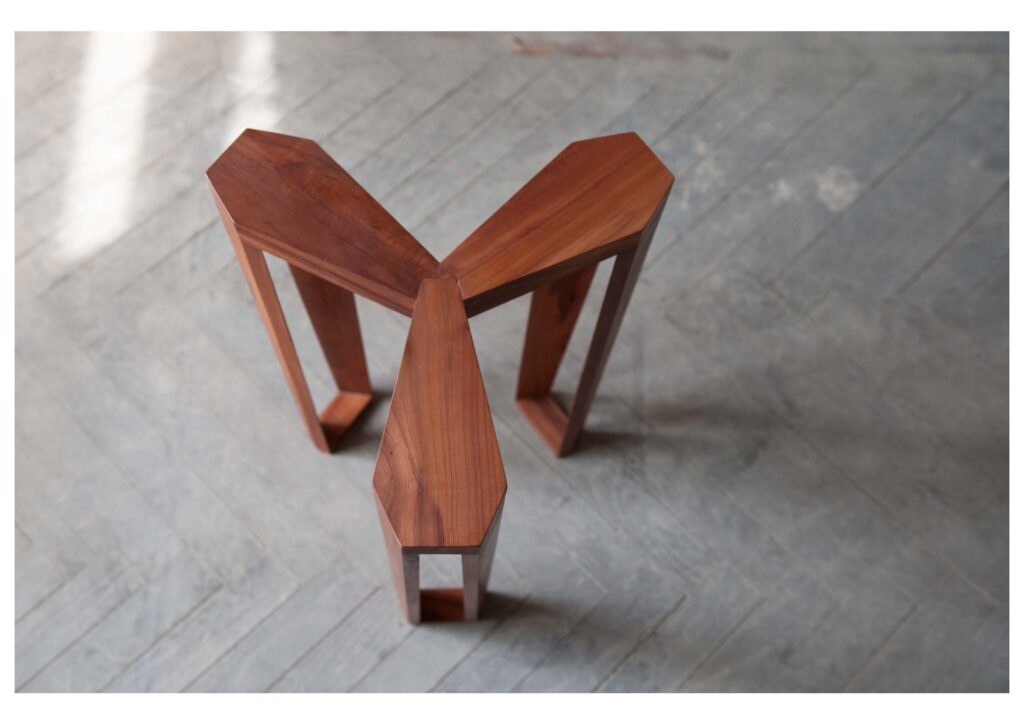

The stool called WALDE

submitted by

Irmgard Frank

Institute of Spatial Design TU Graz, amm ArchitektInnen machen Möbel – Solidwood prototypes from sketch to full scale – Design Philip Waldhuber – Created in 2017 under the direction of Irmgard Frank and Judith Augustinovic and master carpenter Rainer Eberl

The Physical Existence of Objects

In contrast to space, we come into direct contact with furniture. We can see it, touch it, move it, carry it around, etc. Users feel what meaning a piece of furniture holds and what distinguishes it from others.

During my time at the Institute of Spatial design at TU Graz, students were invited to design and realise a piece of furniture. One of the conditions was to work with solid wood, as a representative material we use in architecture. The behaviour of wood – such as shrinkage and swelling, the constructive possibilities, but also the grain of each individual piece – holds enough potential to embody one’s own experiences.

In contrast to a chair, you tend to sit on a stool for only a short time. Yet a certain seating comfort must be provided. Philip Waldhuber’s design, displayed here, is characterised by a minimised construction. Nevertheless, it gives the sitter a feeling of stability.

In addition, the designer’s intention is to achieve something specific and also to express it with it. In this specific case, the student Philp Waldhuber wanted to develop a piece of furniture with a minimised construction. The result is a stool that is surprisingly comfortable to sit on and can also be stacked. When used for other purposes, it can serve as a base for a tray.

The perception: Furniture

In terms of cultural history, furniture, if not a branch of architecture, can be regarded as related to architecture. In the course of human history, furniture has always been an expression of each particular culture and of the lifestyle associated with it. Furniture belonging to so-called “ordinary people” is, in its function, basically different from that of the ruling classes. Reduction to essentials in the sense of universal usability is a characteristic of the furniture of the “simple people”. They had items for storage, to sit on, to lie on, the table and a few variations on these themes such as the cupboard, chest of drawers, bench, chair, dining table and bed. The form of a piece of furniture developed out of the method of production, the function and the nature of particular material used. Nevertheless, despite this reduction to essentials, one finds, time and time again, decorative elements, even among simple pieces of furniture. Through the use of such decoration (carvings, paint, turned elements) the purely functional object became a particular piece which could be aesthetically perceived and sensually experienced by the user.

The Shakers made reduction to essentials (which in their case was a result of the circumstances in which they lived) the basic principle of their life and this is manifested in their architecture, their furniture and the objects of their daily life. In accordance with these premises the appearance of their furniture, among other things, is determined solely by use. Their extensive knowledge of the material wood and the technique of working it and the conscious way in which they used it, along with their precise observation of the processes and rituals of daily life are reflected in the individual pieces of furniture. The intellectual sensibility and the feeling for handicraft from which this furniture comes is the source of its aesthetic quality.

Function and economic methods of construction are the design criteria of Modernism. The analysis of “modern ways of living” for the general public produced a series of “furniture types”. Despite the function-orientated ideology the propagated feeling for freedom, light and air is communicated on the level of aesthetics. Gleaming metal tubing and glass, furniture which is clearly raised off the floor, smooth, mostly pale surfaces, easy mobility, etc. are design tools which can communicate sensual perception. The attempt of Modernism to communicate through architecture a particular, universally valid, approach to life has failed. Above all it failed in its attempt to break up social hierarchies by means of modern architecture. Instead of this we can today observe the phenomenon that the wealthy and the working and middle-class generally search for their aesthetic images in a monarchist past.

The basic needs of man – eating, sleeping and making love – are rooted in the archaic depths of the consciousness and thus closely linked to handed-down values. The change of these values takes place slowly and is minimal. In the social context it is mostly bourgeois notions of how one lives or should live that are decisive. The heterogeneity and variety of opinions which nevertheless exist are a result of projected wishes, different lifestyles or social prestige.

In this context the development of the serial product, the automobile, is particularly fascinating. In this century there is no other product of the Western world which has such an important significant social value as the automobile. There is no other product about which such a degree of unanimity exists amongst very different social classes. The prestige value of a luxury car is not coupled with a particular income group, nor is the associated aesthetic code. It is solely the price of the vehicle which determines who can purchase it.

If one applies these considerations to furniture as a product, one can see quiet clearly that various social groups have their own special aesthetic codes. The prestige value of a particular piece of furniture and its aesthetic coding are directly linked to the view of life and life-style of the user.

The rediscovery of Modernism in the area of furniture, which started in the 1970s, led to the situation in which the possession of a particular piece of furniture acquired a prestige value. The “modern classic” became a cult object. To own one was proof of the owners, progressive lifestyle an interest in culture. The term “modern classic” brings together two opposed worlds. Revolutionary, future-orientated thinking and established bourgeois values are combined in this term.

Furniture and the interior became again, to an increased extent, the means of illustrating a particular approach to life. The criticism of Modernism by the Memphis group and Alchimia was directed at, above all, the dogmatic approach of Modernism and produced as a counterpoint objects whose quality lies in their playful treatment of metaphors and not in their functionalism. These objects, intended as a manifesto, led to innumerable successors, so-called “creative furniture”. Social status was determined according to who produced these objects: a star designer, a successful artist or an unknown newcomer. This game of staging one’s own world took place in a small, affluent, informed or perhaps genuinely interested group.

The major part of the population follows other guidelines in selecting products for the home. In individual cases it may well be that a clever advertising campaign persuades the consumer what he should buy. However “general taste” is much more subtly shaped through films, above all through television films. The films of the 1950s often contained futuristic interiors which matched the future-orientated atmosphere of change predominant at the time. The films of the 1980s and 90s reflect the wish of a saturated consumer society for more security and an associated wariness of any change. If one analyses the interiors which are seen on television and compare these with the furniture generally available on the market – our furniture trade-fairs can give a good overview – one cannot avoid the suspicion that, for a major section of population, the creation of their living environment is carried out according to projected wishes and dreams which are shaped by television.

From the above reflections on the development of various types of furniture we can arrive at a common denominator: namely man’s elementary need for sensual experience. This need is transmitted to every object. There is no such thing as an object of us which can be experienced solely rationally. Seen in this way self-conscious aestheticism is not necessary and is indeed superfluous. The interlocking of very different components contributes to the continuous change of existing products and allows new products to develop. It is these social changes, which lead to shifts in the ways we live and dwell, along with the development of new materials and methods of production which open up new possibilities. Within these paradigms, which establish the framework, there is enough room for interpretation to guarantee a variety of products.

The effect of social, cultural or political tendencies on furniture can be clearly traced. The socio-political ideology of 1968 along with the change in social patterns led to the transformation of some types of furniture. The upholstered seating units which date from this time are the expression of a formlessness in matters of social etiquette. The L- or U-shaped units are the expression of the desired sense of community. Sitting together in a casual group is quite different from sitting around a (dining) table or sitting as individuals in various comfortable armchairs. It is interesting, however, to note that as soon as the force of the ‘68 movement declined, these seating units degenerated into furniture for the non-communicative act of eating crisps together in front of the television. The quality of the first of these seating groups lies above all in the directness with which they radiate what they are and what they stand for. They suggest this with a certain morphological regularity, whose aesthetic code can be unmistakably understood by the viewer or user and which distinguishes them from similar furniture from other decades. The nuances of the particular definition of comfort and also of its value within the context of highly different premises produce, in a concrete case, a spectrum of different variations.

The shift in the values of a society, in this particular case Western society, and the resulting change in the habits of the users combine with new production techniques. According to the particular value which a functional object, a piece of furniture, has, this change can also be seen in the product itself. The bed was – and to a degree still is – of particular importance as a symbol of the most important processes of human existence – procreation, giving birth and dying. There is no other piece of furniture which is so laden with symbols. In the case of traditional beds the head and footboards are structurally necessary but their height an decoration go beyond any such necessity and serve to underline the symbolic content. In bourgeois life the bedroom and its most important element, the bed, was a place to be protected from the inquisitive glances of strangers. Often this room was the largest in the dwelling. If, due the cramped conditions, there was no separate bedroom the bed was kept – at least in the daytime – in a niche, alcove or cupboard. The variety of beds available on the market today – with or without head and foot-board, with or without an integrated shelf, high-off or close to the floor – is also a consequence of the change in the value of this symbolic character. The activities associated with a “comfy” bed are lazing around, resting and making love. Accordingly the bed has mutated to a socially acceptable place to lie on. The altered symbolic message permits a wider spectrum of criteria which govern the selection. Concretely it is individual need and practical considerations along with unarticulated wishes and dreams, concealed behind questions of taste, which today determine the choice.

The difference between relevant and irrelevant designer products lies in the relationship between usefulness, technical know-how and the communication of the sensually perceptible. The extent to which these complex premises are registered by the designer and translated into the product determines its relevance. For this reason it is possible that the so-called anonymous design of several everyday objects is of greater relevance than many a product by “star designers” which, through the dynamics of a market, which is comparable to the art market, may acquire, for a certain period of time, a significance in the media. This results in exaggeration of the value of originality and of being first. The treatment or the further development of something which already exists is an almost unnoticeable process of small steps, completely at odds with the contemporary understanding of creativity. The majority of the population, overstimulated by a computer-generated flood of images flowing past at high speed, has lost the ability to discover – while taking a deep breath – the essence of the images.

It is part of the responsibility of designers to recognise these and other situations and to incorporate their perception in the product. The less coquettish this process is, the more natural the result will be. Ideally it is only our knowledge of the origin of the products which defines the difference between anonymous and consciously developed design.

- @ TACK Exhibition

- @ TACK Exhibition

- @ TACK Exhibition

Submitted by

Irmgard Frank was born in Vienna and studied interior design and industrial design as well as architecture at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. She is a licensed architect with her own firm, and between 1998 and 2018 she was full professor of Spatial Design and Design at the University of Technology in Graz, Austria.

This object is part of the TACK Exhibition “Unausgesprochenes Wissen / Unspoken Knowledge / Le (savoir) non-dit”, in the section “Embodiment and Experience”.