Return to archive

title

BODY OF KNOWLEDGE : KNOWING BODIES

Author

Katharina Voigt

Abstract

This contribution addresses tacit knowledge as an embodied form of knowing and traces the potential of the body to inform and explore, contain and convey, obtain and express architectural knowledge — in the experiencing, designing, creating, and living of architectural space. If, as framed by Polanyi, »we know more than we can tell«, focusing on the body and its immanent knowledge allows to access immediate forms of architectural knowledge. Experience, memory, and the capacity for anticipation are equally rooted in the body; corporeally anchored, contained in, and inscribed to the body. Respectively, creative imagination in architectural design relies upon the body. Through knowing how we experience architecture, we are eager to anticipate future perception in architectural design. Following my doctoral thesis, entitled “Impulses and Dialogues of Architecture and the Body”, I present the knowledge of the body as a contribution to the body of knowledge of architecture: Using the example of the working method and oeuvre of Sasha Waltz & Guests – which I investigate against the background of my own artistic practice, especially in in-situ and site-specific performances, as well as my attempts at the including of somatic practices into my academic teaching in the field of architecture – I exploit the body as a medium of spatial research, and as an immediate form of conveyance and expression in the discipline of architecture.

Embodied Spatial Knowledge

The body of knowledge of architecture is closely bound to the human body’ knowledge: Perception and experience rely upon the body as their tool and medium. In this sense embodied experience and memory form the basis we build upon in the conception, anticipation, and creation of architectural design. Hence all the processes at the core of architectural design are connected to the bodily knowledge. The tacit ways of knowing, which they are linked to, originate from and are rooted in the body. Yet they exploit embodiment as an essential nature of tacit knowledge. Creativity, imagination and the competence to design depend on knowing bodies.

The human body informs how architecture is created, as its continuation and external extension; ‘Gestalt’ and ‘Gestaltung’, gestalt and design, are mutually interdependent. Apart from this physical relationship, body and building intertwine through sensory experience. Francesca Torzo describes it as essential for architectural space to be interconnected with the body, t be lived and embodied, because, as she states, “a space […] is not a space indeed, before it is part of an experience”.

1

Francesca Torzo: Paraphrasing Virginia Woolf for freespace Biennale di Venezia 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–ju_d7CTNM, accessed April 29, 2023.

The living body attunes to it and actively engages with the phenomena of the living world, which it resonates with and dialogically responds to. Human body and built environment are reciprocally interdependent.

Hence, the question is, what and how can we learn from the body? Or, more specifically, how can we make the body’s knowledge, activate and access it?

As it is the nature of body-knowledge, that it is rooted in and mediated through the body – often times beyond conscious recognition – it is the body itself, which serves as a tool and medium to access, convey, and integrate it. Yet, the body itself contains the potential to accentuate, process, and express its genuine ways of knowing. Somatic practices as well as methods and working manners from the field of contemporary dance provide access to a body-based practice of knowledge creation, which allows to ingrate and activate the embodied ways of knowing and to transfer them to disciplinary context beyond the realm of dance, somatic body-work or performative practice.

Spatial Gesture and Bodily Resonance

Due to the interconnectedness of bodily and architectural knowledge, it is worth investigating how the body influences the discipline of architecture. Different modes of the body result in corresponding relations to architecture experiences. Respectively, the experience of architecture also impacts the self-awareness of the body and the way in which the body is somatically perceived. Architectural appeal and gesture affect the architecture’s somatic experience, and furthermore they provide suggestions and impulses for corporeal reaction, they initiate the sensation of being moved – both physically and emotionally.

The intertwining of architecture and the body does not only regard formal, material, or scale related aspects, but also liveliness, movement and interaction – both sensory and socially; “people habitually read movement into unmoving built structures as their form character”.

2

Alban Janson, Florian Tigges, eds.,Fundamental Concepts of Architecture. The Vocabulary of Spatial Situations (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2014 [2013]), 144.

How architectures move us, is negotiated in a responsive process of architectural suggestion, corporeal resonance, and dialogue. We follow architectures’ stimuli, as “we experience such architectural forms as spatial gestures, when we feel addressed in relation to our own behavior, and find ourselves compelled to a performative response”.

3

Janson, Tigges, 144.

We do so, because architecture “can communicate gesturally in ways that are analogous with our understanding of gesture as expressive bodily movement” and they invite us to relate to it corporeally.

4

Janson, Tigges, 144.

Experiential and embodied knowledge is essential for knowing how to anticipate the future architectures’ experiences in the design process. As José Mateus states, “creative imagination [in architecture] draws on experience, memory and all the information and know-how accumulated over time”, because “it lives off – and is totally subject to – the quality of perception with which the creator studies, learns about and relates to the world”.

5

José Mateus, “Imagination”, in: Mariabruna Fabrizi, Fosco Lucarelli, Inner Space, Triennal de Arquitectura de Lisboa (Barcelona: Polígrafe 2019) 2.

Accordingly, the precise knowledge of how architecture affects the body is linked to the learning of how to design from this knowledge. Herein lies the importance of the bodily knowledge for the capacity to anticipate future experiences in the process of architectural design.

The body serves as a medium of experiencing and remembering as well as inventing, imagining, and anticipating architectural spaces. Recalling the memory of past architecture experiences relies just as much on the respective embodied sensations, as does the imagination of future architectural designs. The body’s enormous potential lies in its capacity to facilitate this tacit knowledge, to make it accessible and – especially when trained in somatic practices – allows for the body to express and mediate it. As it is the nature of tacit knowledge that it lays beyond what we consciously know and includes knowing “more than we can tell”, as Michael Polanyi puts it, the body enables us to express it beyond words.

6

Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 4.

American artist Kiki Smith describes the human body, which is at the core of many of her artworks, as this common ground, as she says, »I think I chose the body as a subject, not consciously, but because it is one form that we all share; it’s something that everybody has their own authentic experience with«.

7

Kiki Smith, Anthology from Conversations 1990 to 2016, (in Petra Giloy-Hirtz (ed.): Procession, Haus der Kunst, München 2018), 34.

The body here serves as a point of departure, which everyone can relate to in their individual manner, connecting to their respective experiences and their embodied being. In this way, what we perceived is immediately linked to the body and incorporated to its embodied experience.

Whilst it comes natural to us to use the body as a sensorium and medium of lived experience, its capacity to mediate creativity, conception and designerly invention is not yet unfolded to its full potential. So the question arises, how can we use the body as a medium, tool and source of knowledge in creation and conception, and more specifically in architectural design?

Dialogue – Learning from Contemporary Dance

The working manners in contemporary dance – and somatic practices especially – open a realm of potential to explore the correspondence and interrelation of the body with the world; how we sense, feel and move the body, how our own body relates to other bodies, how the spatiality of the body unfolds into the surrounding space of the body and how the corporeal gesture and gestural expression of architecture correlate, can concisely be studied at the example of contemporary dance – particularly at in-situ and site-specific works – and be exploited with somatic and embodied practices.

How dance works with the architecture’s impulses and influences on the body, becomes particularly clear at the example of the in-situ performances of the Dialogue projects by Sasha Waltz & Guests.

8

Sasha Waltz & Guests, Dialogues, online: https://www.sashawaltz.de/en/productions/#, accessed July 25, 2023.

These experimental formats, which were initially intended to bring together different art forms or methodologies and perspectives from different artistic practices, have more and more evolved around the versatile interrelations of architecture and the human body. The dancers mediate how the architectures affect the human body and how the corporeal dimension of architectural perception can be embodied. Particular aspects of the experience are amplified by this corporeal resonance.

As the terminology of the ‘dialogue’ indicates, it is a reciprocal process of impression and expression, perception and relating, experience and reaction. The lived experience of the architectural space evokes bodily resonances and somatic sensations, which inform the dancers’ movement material. Vice versa, moving in the space and exploring it with the body affects how it is lived and – especially for an audience’s perspective – impacts the experience and perception of the space itself. Witnessing the dancers’ exploration furthermore provides an accentuated empathetic access to embodied experience and somatic sensation, as they are provided the chance to feel with the dancers and to corporeally resonate with their bodily expression.

Embodying Spatial Experience

For my research I spoke with Sofia Pintzou, a dancer who contributed to the “Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch”, a video journal with excerpts from different pieces of the company’s repertory, performed and recorded in the personal living environments of the dancers, due to the restrictions and prohibiting of rehearsals and performances during the pandemic induced confinements. 9 Sasha Waltz & Guests, »Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch«, online: https://www.sashawaltz.de/keep-on-dancing-sasha-waltz-guests-tanztagebuch/, accessed July 25, 2023. From her contribution it becomes particularly apparent how the body serves as a tool and medium to explore architectural space and to convey sensory, space related embodied experience.

Fig. 1.

Sofia Pintzou, contribution to »Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch«, 2020, interpreting choreographic material from Sasha Waltz’ »noBody«, first performed 2002 at Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin, film stills from the video, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bj-dVgonIT0, accessed July 25, 2023.

In our conversation, Sofia Pintzou described the sensory experience of the limitedness of space as a point of departure and source of inspiration for her interpretation of the movement sequences from Sasha Waltz’ “noBody”

10

Sasha Waltz & Guests, »noBody«, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bj-dVgonIT0, accessed July 25, 2023.

, which she situated in her apartment.

11

Sofia Pintzou’s contribution to the »Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch« is available online

Her experience of this personal living environment at the time was closely linked to how she perceived her part in “noBody”; “a small, yet very specific one”, as she says, “because it was inherent to this position that I was always working against some withstand or a threshold that I could not reach beyond. As if I could not express myself; as if I was stuck and not able to get out”.

12

Sofia Pintzou, in Conversation with Katharina Voigt, in: Katharina Voigt, Impulse und Dialoge zwischen Architektur und Tanz, Dissertation, July 2023, 456–457.

These movements also affected the somatic experience of her body: “it was like carrying no body, or rather, carrying a body with fragmented and deteriorated possibilities to express emotions, sensations or motivations. There were moments in the piece for expressing emotions, but only few, which dramaturgically makes ›nobody‹ such a strong dance creation”.

13

Ibid., 457.

In her interpretation of this sequence she picks up the sensory experience of working against a wall and shifts its spatial dimension to the ceiling. Arching the back and bending backward – which is another omnipresent posture and movement-material in “noBody” – Sofia Pintzou explores the intermediate state of drifting, falling, working against and being repelled from the ceiling above as a plane which she is facing.

The way how she embodied these aspects extracted from the spatio-corporeal experience of “noBody” – going against a withstand, floating in space, falling and being repelled, drifting or floating in space – resulted in corresponding somatic experiences. The compacted lower back provides a densification, contraction and stability of the core of the body, while the arching of the back and the backward bend result in opening the chest, which equally leads to expansion and exposure of the front side of the body, making it perceptive and connect it to the plane of the ceiling which it is facing. Embodying the experience of a limited space leads to the creating of new spatial and bodily possibilities, which would hitherto not have existed and that are – as opposed to the original impulse, which stems from the experiencing of the space and its sensory and somatic effects – linked to contrary experiences of expansion, openness or exposure.

From Embodied Perception to Architectural Conception

As the example of Sofia Pintzou’s contribution to the »Sasha Waltz & Guest’s Tanztagebuch« illustrates, the experience of architectural space and the related somatic sensations are closely linked and reciprocally dependent. Furthermore, their respective transformations are interlinked. In the perception and experience of architecture somatic and embodied sensations are evoked from how the built environment affects the human body. Respectively, the body and embodied sensations can also serve as medium and tool to conduct conceptual inventions, in the sense of conception as an inverted process of perception and a creative learning from, a reassembling and transforming of the knowledge acquainted through experiencing. The embodying and corporeal tracing of lived experiences evoke new possibilities of somatic sensations, which can lead to further insight into spatial qualities and characteristics that can inform a consecutive process of architectural design.

This track of thinking has informed my intentions for the set-up of a design studio “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”.

14

“Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis with the task to design a dance-house in Munich, winter term 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff. For further information please see: https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/eundg/lehre/master/zentrale-masterarbeit/, accessed July 25, 2023.

Here we took the somatic experience of the body as a point of entry to the process of architectural design. This design studio was opened with a workshop that introduced somatic practices and explored different manners of working in the field of contemporary dance. In this context the students were invited to explore spatial characteristics and qualities with and through their bodies. In regard to the task to design a dance-house in Munich, which assembled spaces of different uses to house the full spectrum of activities in dance, the complementary qualities of ›intimacy‹ and ›public‹ were considered core characteristics of this architecture. It was an essential aspect of the following design process to elaborate a variety of spaces of intimate or public character, and to dedicate particular awareness to their in-between spaces, as interstices or thresholds between these complementing spheres.

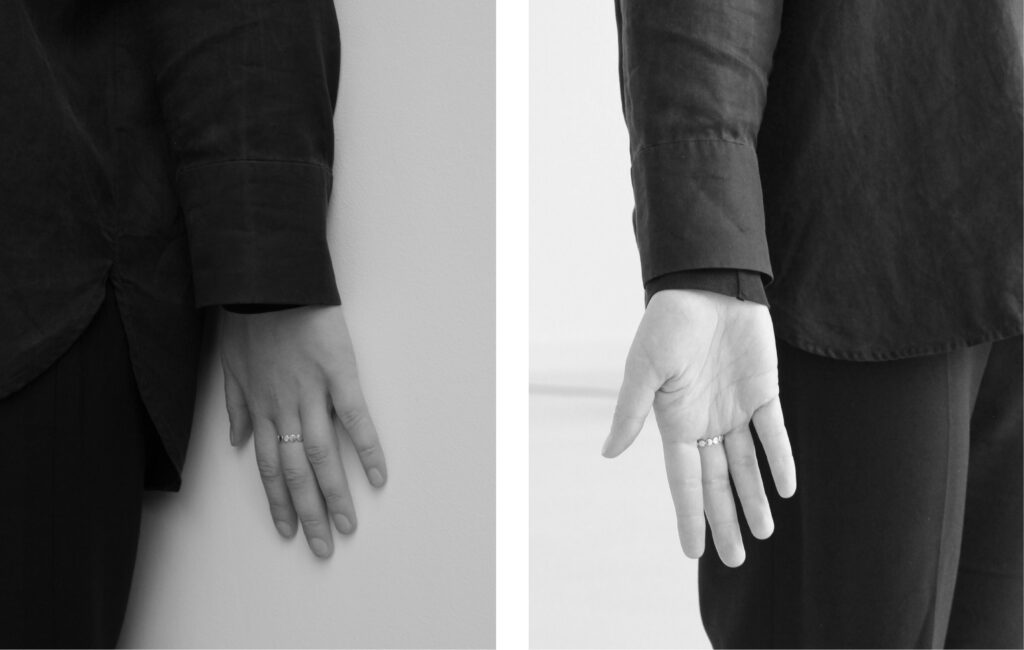

Fig. 2.

Antonia Krabusch: Embodied Gestures, Gesture of Intimacy (left) and Gesture of Public (right), initial task for the design studio “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis, winter 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff.

Closing and opening, contraction and expansion, or containing and presenting were formulations used to describe of these complementary aspects of intimate and public gestures, experiences, and spatial qualities. Antonia Krabusch reduced their expression and gesture to the simple movement of the hand: Showing the back of the hand, the intention was at shielding or contain something in the palm of the hand. Leaning against a wall, this gesture held a narrow, enclosed space between, spanning between the wall and the slightly bent palm of the hand. Opening her hand, the palm facing front, did not only expose the inner side of her hand, which had in the first, intimate gesture been shed by the back of the hand, but it also resulted in an overall opening of the front side of the body – and therewith an open and welcoming attitude, which signifies availability and improves the presence of the person and encourages an active approach to the world.

Fig. 3.

Lukas Walcher: Embodied Gestures, Gesture of Intimacy (left) and Gesture of Public (right), initial task for the design studio “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis, winter 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff.

But the embodied gestures did not only explore the somatic experience of ones own body and its lived experience, but for some students they also included spatio-corporeal aspects of how the body relates to the surrounding space and how it moves therein. Like Lukas Walcher did, they explored gestural expressions and movements, which added to the sensation of, on one hand, being with themselves – as an expression of the characteristic of intimacy, involving the sensation of being contained and protected, shifting the focus away from the world around and to an introspective, sensory and somatic sensation of the body. On the other hand they embodied the potential of opening the focus to the world, perceiving what surrounds them, and creating possibilities for encounter.

In many cases the corporeal gesture informed the architectural gesture of the design. As a second step, these gestures, embodying an intimate and public sensation or movement, were transferred into an architectural object, translating these characteristics and their lived experience into an assemblage of intimate and public spaces and their in-between realms in the form of interstices, thresholds or spatially articulated sequences. The way in which the embodied sensations and corporeal gestures were translated or transferred into corresponding spatial gestures and architectural forms, raged from direct adaption of the bodily shape and gesture into the physical object to an architectural interpretation associated with the somatic experience, and further to a transfer of the spatial quality of the embodied gesture to an architectural form.

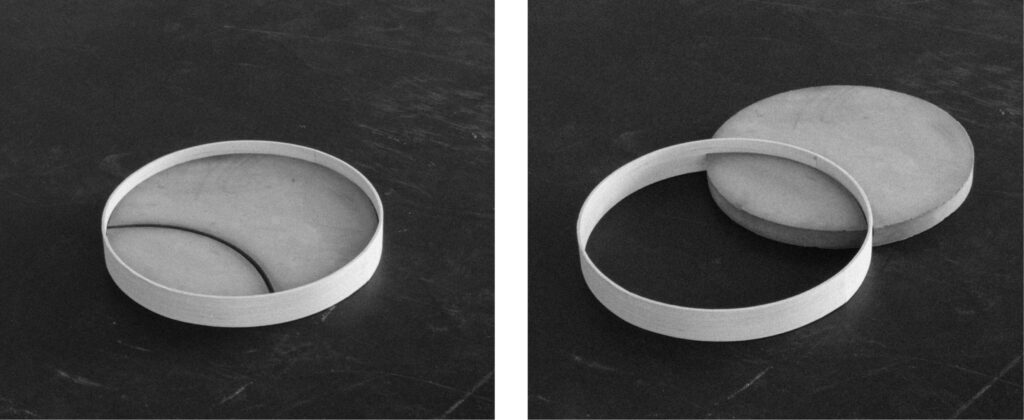

Lukas Walcher drew the shape of the architectural object from the circular movement of the encounter with oneself in the half-circle movement of the gesture attributed to the experience of ‘public’: An equal sized round concrete disc and a ring of plywood fit together in different constellations. The cut surface resulting from their overlap is enclosed by both elements, which intersect here and fit precisely into each other through corresponding cutouts.

This object allows for several interpretations; the open plane can be associated with the public quality of an exposing or presenting stage, the surrounded space that is framed by the wooden ring, can be read as a contained space of a rather intimate nature. Yet, the smallest and most enclosed spatial situation elicits in the intersecting part of both, which is rimmed by the plywood wall on one side and an engraved relief of a level-change in the concrete plane on the other side. Considering this the space of intimacy rather than the interstice between the two circular spaces of different character, the round plane and the framed space appear to be two different kinds of public spaces – an exposed, stage like open plane and a limited and framed open space.

Fig. 4.

Lukas Walcher: Architectural Object, initial task for the design studio “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis, winter 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff.

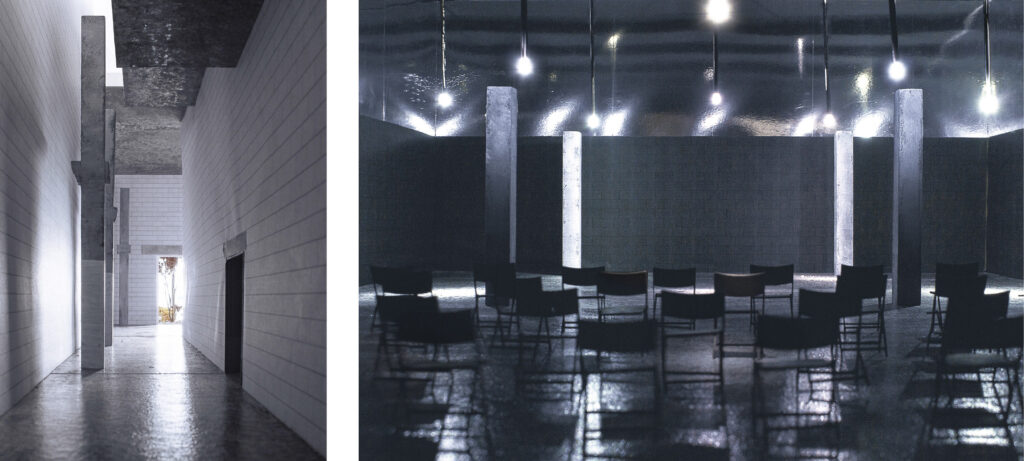

This ambiguity of spatial characteristics and architectural expression remains present in Lukas Walcher’s architectural design of the dance-house. Also here, spaces of public use – like the performance hall – are designed with dedication to rather intimate architectural quality and yet the transitional spaces like the corridors and foyers as well reveal a nature of intimate, protected and contained spatial character.

Fig. 5.

Lukas Walcher: Interior of the Foyer and the Performance Hall, “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis, winter 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff.

The essential characteristics that were elaborated through somatic practice and the sensory tracing of bodily perception and movement remained present in the design process and are still retraceable in the spatial qualities and ambiances of the finalized architectural conception.

Knowing Bodies

Experiential knowledge of architectural perception and anticipation of future architectural experience in the process of architectural design are interdependent and build upon each other, as the first forms the prerequisite for the latter. Consequently, we can learn a lot about how to design architecture from an understanding of how we experience it. TAs the experience, memory and anticipation of architecture rely upon the body as their subject, their medium, sensorium, and tool, a deeper understanding of the body and its genuine ways of knowing forms the basis from which any kind of architectural imagination elicits.

In order to tackle the tacit knowledge in architecture – which is to be understood as an embodied knowledge, both in the aesthetic practices of designing, creating and making architecture, as well as in its lived experiences and the recalling of their memories – the body needs to be taken into account. Unfolding the potential of its versatile ways of knowing by engaging into body-based, somatic, or embodied practices unravels new methodologies and processes for architectural design as well as the creation of knowledge in the architecture discipline. Thus, elaborating the body of knowledge of tacit knowledge in the architecture discipline is linked to the human body as a body of knowledge. As we know “more than we can tell”, it is the body’s potential to ‘speak’ and mediate this knowledge.

- Francesca Torzo: Paraphrasing Virginia Woolf for freespace Biennale di Venezia 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–ju_d7CTNM, accessed April 29, 2023.

- Alban Janson, Florian Tigges, eds.,Fundamental Concepts of Architecture. The Vocabulary of Spatial Situations (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2014 [2013]), 144.

- Janson, Tigges, 144.

- Janson, Tigges, 144.

- José Mateus, “Imagination”, in: Mariabruna Fabrizi, Fosco Lucarelli, Inner Space, Triennal de Arquitectura de Lisboa (Barcelona: Polígrafe 2019) 2.

- Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 4.

- Kiki Smith, Anthology from Conversations 1990 to 2016, (in Petra Giloy-Hirtz (ed.): Procession, Haus der Kunst, München 2018), 34.

- Sasha Waltz & Guests, Dialogues, online: https://www.sashawaltz.de/en/productions/#, accessed July 25, 2023.

- Sasha Waltz & Guests, »Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch«, online: https://www.sashawaltz.de/keep-on-dancing-sasha-waltz-guests-tanztagebuch/, accessed July 25, 2023.

- Sasha Waltz & Guests, »noBody«, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bj-dVgonIT0, accessed July 25, 2023.

- Sofia Pintzou’s contribution to the »Sasha Waltz & Guests’ Tanztagebuch« is available online

- Sofia Pintzou, in Conversation with Katharina Voigt, in: Katharina Voigt, Impulse und Dialoge zwischen Architektur und Tanz, Dissertation, July 2023, 456–457.

- Ibid., 457.

- “Tanzhaus München – ein Ort für zeitgenössischen Tanz”, general masters’ thesis with the task to design a dance-house in Munich, winter term 2021/22, Chair of Architectural Design and Conception, supervised by Katharina Voigt and Prof. Uta Graff. For further information please see: https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/eundg/lehre/master/zentrale-masterarbeit/, accessed July 25, 2023.