Return to archive

title

Crackpot’ and ‘Dangerous’: On the authenticity of Miesian reproductions

author

Hamish Lonergan

Abstract

In 2016, the architectural press reported the planned reconstruction of Mies van der Rohe’s Wolf House, built in 1927 in Gubin, Poland, and destroyed during World War Two. Supporters claimed that, by consulting the architect’s presentation drawings, they could rebuild the house authentically. They cited a simplistic reading of philosopher Nelson Goodman’s distinction between autographic art—where an original is certified by the hand of the author—and the allographic, which is replicated through notation. Barry Bergdoll called the proposal ‘crackpot’, arguing that without the lost construction documentation it would become a ‘simulacrum’: an allusion to Jean Baudrillard’s notion of a copy without reference. Mies himself thought there was something ‘dangerous’ in building ‘a model of a real house’ after constructing his own full-scale façade mock-up for the unbuilt Kröller-Müller House (1913). Since then, an unprecedented number of reproductions have entered into their own ‘dangerous’ conversation with Mies’ work, trading to varying degrees on their authenticity. Some, like the Barcelona Pavilion reconstruction (1986) engage with heritage and archival practices in an attempt to accurately reconstruct a lost work. Others, often appearing in exhibitions such as OMA’s La Casa Palestra at the 1985 Milan Triennale, exploit the fame of Mies’ architecture to offer a rhetorical interpretation that reinforces their own authorial signature. Meanwhile self-professed 1:1 models, like Robbrecht en Daem’s Mies 1:1 Golf Club Project (2013), seem deliberately tied to Mies’ authority, stripping away materials to focus on a singular reading of the work in a model-making tradition stretching back to Alberti. By returning to Goodman’s autographic/allographic dichotomy and Baudrillard’s simulacrum, this paper seeks to make sense of these multiplying reproductions across art, architecture and conservation, and their conflicting claims to authenticity. Ultimately, this frames Miesian reproductions as one contested site in broader discussions of architecture’s relationship to authorship and authentic heritage.

It is noteworthy how often Ludwig Mies van der Rohe is photographed with his models. He peers at us between buildings, points out features to clients and colleagues, and bends down to see the Farnsworth House from ground level. Beatriz Colomina notes that Miesian histories nearly always comment on his substantial figure, but in the play of scales in these images he appears monstrous. 1 Beatriz Colomina, ‘Mies Not,’ in Presence of Mies, ed. Detlef Mertins, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 169. For Vitruvius, scale models were untrustworthy. Writing in the Ten Books of Architecture, he warned ‘not all things are practicable on identical principles’: that some things that seem reasonable at small-scale are proven impossible or unsuccessful when built. 2 Although this passage appears in chapter 10, where Vitruvius discusses the use and construction of machines, he is clear that the models of machines he discusses were constructed by architects. Vitruvius, The Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Morris Hicky Morgan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914), 317. Nonetheless, since the Renaissance, scale models have assumed a fundamental role, alongside drawing and writing, in developing and expressing architectural ideas. Indeed, the 20th Century seems to have witnessed the reversal of Vitruvius’ formulation. Whereas small-scale models are interpreted as crucial to Mies’ architecture and reputation, the profusion of life-size reproductions—from both van der Rohe himself and others—have been more difficult to assess.

This paper reflects on an unprecedent number of Miesian reproductions in the last fifty years, and the way they enter into a dialogue with history: drawing on Mies’ authority while asserting new interpretations. At the same time, they are inevitably transported to a different time and place, resulting in slippages—both deliberate and accidental—from the original, which affect perceptions of their authenticity. In this paper, following a detour to the Kröller-Müller House, I consider three broad categories of reproductions: proposed and actual reconstructions, such the Wolf House and Barcelona Pavilion; speculative, artistic interpretations such as La Casa Palestra; and self-professed 1:1 models, such as Robbrecht en Daem’s 1:1 Golf Club Project. In examining these multiplying Miesian reproductions across art, architecture and conservation, we can begin to understand what their appeal tells us more broadly about those closely related notions of authority, authorship and authentic heritage.

Uncanny Copies

Mies himself had an ambiguous relationship with full-scale versions of his work. In 1912, he oversaw construction of a full-scale façade mock-up of his Kröller-Müller House proposal, in painted sailcloth and timber. 3 Mies began the project working as Peter Behrens’ assistant. In 1912, a first full-scale mockup was commissioned of Behrens’ proposal. Later that year, Mies left Behrens’ office and assumed the commission himself, constructing a second mock-up of his own proposal. See Detlef Mertins, Mies (London: Phaidon Press, 2014), 44-55; Franz Schulze and Edward Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography (Chicago and London: The Uiversity of Chicago Press, 2012), 37-43. The proposal was rejected; he lost the commission to Hendrik Petrus Berlage, whose scheme was also never constructed. Even in these circumstances, without an original ever existing off the page, Mies later agreed that that it was ‘dangerous to build a model of a real house’ at full-scale; he is characteristically, and frustratingly, laconic on the precise nature of this danger, saying only that ‘50,000 guilders is a lot of money’. 4 Henry Thomas Cadbury-Brown, ‘Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in conversation with H T Cadbury-Brown,’ AA Files no. 66 (2013): 71 Carsten Krohn speculates that this danger relates to the reduction of the complexity of architecture to a two-dimensional impression: capturing massing but lacking material qualities and a true sense of place. 5 Carsten Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe: The Built Work, trans. Julian Reisenberger, (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2014), 80. It is tempting, however, to interpret Mies’ fear more existentially. As Hillel Schwartz notes, Modernist literature is full of doppelgangers and evil twins, who usurp their original’s place in society. 6 Hillel Schwartz, The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles (Cambridge, MA.: Zone Books, 2013). On the copy in architecture, see Ines Weizman, ‘Architectural Doppelgängers,’ AA Files, no. 65 (2012): 19-20, 22-24. For Freud, the double was deeply uncanny: ‘a vision of terror’ that recalled ‘the sense of helplessness experienced in some dream-states’. 7 Sigmund Freud ‘The “Uncanny,’ in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, trans. Alix Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press, 1919), 217-256. If a model can do so much—complete with ‘partitions and ceilings [that] could move up and down’—clients might wonder why they should ever inhabit real architecture at all.

Since then, the Kröller-Müller House has accumulated a cult following. Commentators, from art historian Paul Westheim to critic Paul Goldberger and architect Rem Koolhaas, saw the lightness of the mock-up as the bridge between early works, influenced by Schinkel’s classicism, and the glass ephemerality of the Barcelona Pavilion (1929) and Friedrichstrasse skyscraper proposal (1922). 8 Mertins also reads a strong connection to Berlage’s geometry and Wright’s organic architecture. Mertins, Mies, 44-55; Paul Westheim, ‘Mies van der Rohe – Entwicklung eines Architekten,’ Das Kunstblatt, vol. 2 (1927), 56, quoted in Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe, 25; Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S M L XL (New York: the Monacelli Press, 1995), 63; Paul Goldberger, ‘Architecture: Mies Show at Modern’, New York Times, Feb. 10, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/02/10/arts/architecture-mies-show-at-modern.html. In many ways, reactions to subsequent reconstructions were prefigured in the reception of the Kröller-Müller House: alternatively viewed as a seductive opportunity for reinterpretation, or as a pale, inaccurate and uncanny reflection of an existing or projected original.

Authenticity or Simulacrum

Mies’ Wolf House is a useful place to begin this account: built in 1927 in the German city of Guben and largely destroyed in World War Two. Becoming part of Poland as the iron curtain dropped—the city renamed Gubin in the process—there had been relatively little interest in the house until recently, despite Wolf Tegethoff judging it Mies’ ‘first opportunity to translate into actual fact the ideas he had developed in his two country house projects’, 9 Wolf Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe: The villas and country houses (Cambridge, MA. and London: MIT Press, 1985), 58. a sentiment echoed by Barry Bergdoll. 10 Bergdoll called it ‘the first building in which Mies was able to bridge the gap between his commissioned work and his ideal projects’. Barry Bergdoll, ‘The Nature of Mies’s Space,’ in Mies in Berlin, ed. Terence Riley, Barry Bergdoll and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2001), 87. In part, this was due to a paucity of physical remnants—garden terraces, a driveway and a basement—and a limited set of presentation and construction drawings, with carefully controlled exterior photograph, almost entirely lacking images of the interior. 11 See Bergdoll, ‘The Nature of Mies’s Space,’ 88; Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 58-59. In 2016, however, a string of articles appeared in the English-language architectural press for the first time, reporting that a German foundation planned to reconstruct the house on its original site. 12 See Gerrit Wiesmann, ‘A Push to Rebuild a Modernist Gem by Mies,’ New York Times, Mar. 21, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/arts/design/rebuilding-a-modernist-gem-from-mies-van-der-rohe.html; Anna Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork,’ Architectural Record, Apr. 21, 2016, https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/11624-scholars-debate-the-fate-of-a-lost-mies-masterwork; Robin Oomkes, ‘Recreating Mies’ Villa Wolf at Gubin,’ Dead Emperors’ Society, Apr. 10, 2016, https://deademperorssociety.com/2016/04/10/recreating-mies-villa-berg-at-gubin/.

In German universities, the proposal had already become a minor architectural controversy. As early as 2013, a former president of the German Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Florian Mausbach, launched a foundation tasked with reconstructing the villa as a 1:1 model, in time for the Bauhaus Centenary in 2019. 13 ‘Milestones,’ Mies van der Rohe Museum: Villa Wolf Gubin, accessed on August 20, 2020, https://cargocollective.com/villawolfgubin/Meilensteine In 2014, the foundation collaborated with researchers and students from the Potsdam University of Applied Science to document the site and accumulate all available information on the house, including interviews with Wolf’s children. 14 ‘Reconstruction of the destroyed Villa Wolf (Gubin) by L. Mies van der Rohe,’ Fachhochschule Potsdam University of Applied Science, January 4, 2015, https://www.fh-potsdam.de/forschen/projekte/projekt-detailansicht/project-action/rekonstruktion-der-kriegszerstoerten-villa-wolf-gubin-von-l-mies-van-der-rohe/. Although researchers there ultimately concluded that there was insufficient documentation for a full reconstruction, in 2016 the foundation officially launched the project and, in 2019, they held an exhibition and conference, with presentations from major Miesian scholars, including Tegethoff. At the same time, opposition continued from other prominent figures in German academia: a letter calling for a ‘contemporary interpretation’ rather than a reconstruction was signed by over forty professors of architecture in 2016. 15 Franco Stella, ‘Discussion about how to deal with the Wolf House in Gubin,’ Cultural Heritage Center, Brandenburg Technical University, 2016, https://www.b-tu.de/cultural-heritage-centre/diskussion/haus-wolf-in-gubin#c109435.

I am less interested, here, in the specific approaches to this reconstruction, than the competing philosophical frameworks of authorship and authenticity in the debate. Dietrich Neumann—a professor at Brown University, advising Mausbach—suggested they knew more about the Wolf House than the Barcelona Pavilion. Indeed, thirty years earlier, Tegethoff had catalogued 98 surviving plans for the house, from initial concept and building approval to construction. 16 Tegethoff, however, does note inconsistencies between elevations and plans, and difficulties in dating certain drawings. Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 58-59. Like the Barcelona Pavilion reconstruction, Neumann argued that the experiencing the house on-site at full scale had more to offer visitors and scholars than these plans and photographs alone: ‘haptic and sensuously tangible in different times of the day and year within its context with the views overlooking the river Neisse’. 17 Dietrich Neumann, ‘Visions’, e-architect, 21 May, 2017, accessed on 1 November 2020, https://www.e-architect.com/poland/wolf-house-guben-by-mies-van-der-rohe.

On the charge of inauthenticity and artificiality, Nuemann cited philosopher Nelson Goodman and his distinction between autographic and allographic arts. 18 Neumann, quoted in Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork.’ Autographic arts value an original because of its direct connection to the artist, meaning that a forgery will never be genuine, no matter how accurate. 19 Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrilll Company, 1968). Allographic arts have no original. Like dance or symphonic music, artists and performers produce an authentic version by following a script or other notation of the work. Nuemann claimed that architecture is an allographic art and so an authentic version of the Wolf house could be created from the available plans. Goodman, however, concludes that architecture is an interstitial case: working from a plan, which is like notation, but historically tied to a single author and instance. 20 Goodman, Languages of Art, 221.

For critics, this defence seemed to miss the point. Leo Schmidt, professor of architecture at Brandenburg Technical University, argued that ‘rebuilding the Wolf House as an empty shell would not deepen our understanding of Mies…we know very few details…The rebuilt house could end up with bare, white-walled rooms’. 21 Schmidt quoted in Wiesmann, ‘A push to Rebuild a Modernist Gem by Mies.’ The problem was less an issue of Mies’ missing signature, than the scarcity of detailed documentation: floorplans were not enough. Bergdoll called the proposal ‘crackpot’, arguing that even an ideal version of the Wolf house—originally built in brick and plaster—would have none of the reflective, phenomenological qualities that made the reconstructed Barcelona Pavilion worthwhile. It would, instead, become a ‘simulacrum of the spatial sequence.’ 22 Bergman quoted in Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork.’ This seems an allusion to the philosophy of Jean Baudrillard and his argument that, in a Postmodern world, simulacra become copies without an original, ‘never exchanged for the real, but exchanged for itself, in an uninterrupted circuit without reference or circumference.’ 23 Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6. Although a version of the Wolf House had existed once, Bergdoll implied that the lack of documentation meant there was no true reality for the reconstruction to reference, becoming an inauthentic symbol divorced from the reality of the building remnants on site.

Two Barcelona Pavilions

Debate surrounding the Wolf House frequently invoked the earlier reconstruction of the Barcelona Pavilion: first constructed for the German section of 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition, before it was dismantled in 1930. In 1986, Ignasi de Solà-Morales, Cristian Cirici and Fernando Ramos reconstructed the pavilion from archival photographs and plans. Some scholars, including Neil Levine and Juan Pablo Bonta, argue the reconstruction is less effective at describing and preserving the space than photographs or written description. 24 Neil Levine, ‘Building the Unbuilt: Authenticity and the Archive,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historian 67, no. 1 (Mar 2008): 14-17; Juan Pablo Bonta, An Anatomy of Architectural Interpretations: A Semiotic Review of the Criticism of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1975).

Yet Bergdoll is not alone in praising its experiential, reflective qualities. 25 For a detailed account of the intellectual, heuristic implications of this mirroring, see Mertins, Mies, 149-155. Robin Evans’ account of the multiplying, mirroring surfaces is particularly poetic: ‘notice the difficulty of distinguishing the travertine floor, which reflects the light, from the plaster ceiling, which receives it…Here, Mies used material asymmetry to create optical symmetry.’ 26 Robin Evans, ‘Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,’ AA Files, no. 19 (1990): 63– 64. It is telling that Evans credits Mies with these reflective qualities, neglecting even to mention Solà-Morales and his collaborators by name.

Indeed, accounts of the building—in both popular and academic discourse—tend to attribute the effects of the reconstruction to Mies alone, to say nothing of Lilly Reich’s contribution. 27 Reich was artistic director of the German contribution to the Barcelona Exhibition but, as Colomina argues, it is an open secret that she also influenced Mies’ ‘radical approach to defining space by suspending sensuous surface’. Beatriz Colomina, ‘The Private Life of Modern Architecture,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58, no. 3 (Sep 1999): 462-471. According to Jorge Otero-Pailos, this is typical of preservation architecture. He writes that ‘preservation’s central expressive ideal is self-effacement,’ yet, at the same time, total self-effacement can become indistinguishable from the original, falsifying and undermining its authenticity. 28 Jorge Otero-Pailos, ‘On self-effacement: the aesthetics of preservation,’ Place and Displacement: Exhibiting Architecture (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2014), 231 Paradoxically, in the erasure of Solà-Morales’ authorship, the Barcelona Pavilion comes close to this falsification. The difficulty was that the pavilion had already become a familiar icon through the same fragmentary photographs and presentation plans used in its reconstruction: the 13 Berliner Bild-Bericht photographic prints, favoured by Mies in publications, lacking as-built construction drawings. 29 See George Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces: Desiring the Barcelona Pavilion,’ RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no 39 (Spring 2001): 168-191. In prioritising visual fidelity to this icon in their reinterpretation—despite the lack of precise documentation raised in the Wolf House debate—the architects’ reconstruction was wholly subsumed in an idea of Mies’ pavilion, with none of the critical distancing devices that have increasingly played a role in heritage discourse.

Without such devices, all reconstructive decisions are evaluated against what can be determined of the original. Schulze and Windhorst note that modifications were needed to turn a temporary pavilion into a permanent one—’correcting original flaws, including a sagging roof widely commented on in 1929-30’—but scholars frequently catalogue less deliberate discrepancies. 30 Schulze and Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe, 125. See also Jonathan Hill, ‘Weathering the Barcelona Pavilion,’ The Journal of Architecture 7, no. 4 (2002): 319-327; Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces’, 177 Krohn is especially scathing. He writes that the roof is made of the wrong materials, the glazing and onyx are the wrong shade and that the red curtain is not present in any original images. 31 Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe, 80. Mertins, however, cites the velvet curtain as part of Reich’s furnishings for the original pavilion. Mertins, Mies, 14 In this way, Kohn represents the authority of the Barcelona Pavilion reproduction as wholly drawn from Mies, while the authenticity of that reproduction is brought into question through deviances from the original.

It was precisely this sort dissonance with an original and the impossibility of bringing the archive to life that spurred La Casa Palestra. Staged by OMA/Rem Koolhaas at the 1985 Milan Triennale, it beat the official reconstruction in Barcelona into existence. According to OMA, their version confronted a dominant account of Modernism as lifeless and severe, by dynamically curving the plan and filling it with exercise equipment and bodybuilders. 32 Office for Metropolitan Architecture, ‘La Casa Palestra / Town Hall and Library, the Hague,’ AA Files, no. 13 (1986): 8-15. At the same time, the installation was in dialogue with what Koolhaas labelled the ‘clone’ in Barcelona. La Casa Palestra was intended to approach a ‘higher authenticity’ by uncovering the building’s history rather than recreating it. Koolhaas claimed to have traced the pavilion’s original materials to a dank locker room, built and never used for the 1952 Olympics. Looking back from 1995 in S, M, L, XL, he asked ‘how fundamentally did [the clone] differ from Disney?’, 33 Koolhaas and Mau, S M L XL, 49. but of course his own history was a fabrication. The pavilion was dismantled and the materials sold to offset the cost of construction.

Like Bergdoll before him, by invoking Disney, Koolhaas seems to refer to Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, published to acclaim and controversy more than a decade earlier. For Baudrillard, Disneyland is the ‘perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulacra’. 34 Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 12. Elsewhere in S M L XL, Koolhaas explicitly references Baudrillard. Koolhaas and Mau, S M L XL, 967. Both Levine and Dodds also raise the spectres of ‘Disneyfication’, simulacrum and Baudrillard in discussing the Barcelona Pavilion. Levine, ‘Building the Unbuilt’; Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces’. Not only does it mask its own garbled original—two-dimensional and inaccurate representations of pirates and the Wild-West—but Disneyland becomes a ‘deterrence machine set up in order to rejuvenate the fiction of the real’. 35 Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 13 Although it is sometimes difficult to know how far he trusts his own rhetoric, according to Baudrillard Disneyland exists to disguise the total absence of reality beyond its walls. The world outside has become ‘hyperreal’, full of references and differences, but with no referent at all: not even the faint original of the Wild West.

Read in this way, Koolhaas’s project seems to question the very basis for a truly real or authentic reconstruction, particularly from the disjointed history depicted in the available plans and photographs. And in constructing his own version of Mies’ work, he implies the impossibility of any originality and authenticity in architecture at all. Framed in this way—leveraging a relationship to the supposed-original to argue his own position through architecture—OMA could claim to be the building’ designer while being entirely transparent in their references to van der Rohe.

Artistic License

Full-size interpretations of Mies’ work since have entered into a similar conversation, with clear visual references to an original, but attributed to their artistic creator. Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s installation Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With (2009), upturned a 1:1 model of the conceptual 50×50 House (1951). Even in this abstract presentation of a little-known and never-built house, its material detailing—with exposed universal columns—reveals links to Mies’s oeuvre, particularly the Farnsworth House. Manuel Peralta Lorca’s Welcome Less Is More (2010) replaced the Farnsworth House’s glass, travertine, primavera timber and white-painted steel with plywood and pine. In 2010, Bik van der Pol reproduced the house in white in are you really sure that a floor can’t also be a ceiling? (2011), filling the interior with plants and butterflies, while still replicating the original’s steel details.

These forms, materials and details are distinctive enough for even non-architects to recognise. Repetition of certain strong formal devices—floating planes, cruciform chrome columns—make it easier to reference the original, even when changing materials or bending the form. Meanwhile, Mies’ career was intrinsically tied to photography, magazines and exhibitions, which allowed him to establish a reputation in America even before arriving there in 1937, from a handful of houses, unbuilt projects and the Barcelona Pavilion. 36 See Detlef Mertins, ‘Goodness Greatness: The Images of Mies Once Again,’ Prospecta 37 (2005): 112-121; Claire Zimmerman, ‘Photography into Building: Mies in Barcelona,’ Photographic Architecture in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 49-83; Colomina, ‘Mies Not,’ 193-221. Since then, images of the work have regularly appeared in exhibitions and mainstream newspapers. In 2019, a Timeout listicle ranked Mies the third best architect of all-time, behind Guadí and Frank Lloyd Wright. 37 Howard Halle, ‘The best architects of all time, ranked,’ TimeOut, June 25, 2019, https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/best-architects-of-all-time-ranked.

Artists and architects have exploited this distinctive consistency to enter into their own dialogue. Differing from Miesian models at reduced size—Callum Morton’s International Style (1999) or Erwin Wurm’s Mies van der Rohe Melting (2005)—full-scale reproductions deliberately leverage their uncanny, life-size relationship. In faithfully replicating scale and other iconic characteristics, departures from the well-known originals are especially noticeable, taking on a pointed, critical dimension.

Indeed, unlike the intended-fidelity of the Wolf House or Barcelona Pavilion reconstructions, these installations draw discursive power from their brazen inaccuracies. The furnishings inside Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With included a violently overturned tea cup and a voice-over alluding to the sudden loss of gravity, intended to make us question the differences between dystopia and Mies’ modernist utopia. 38 Denise Markonish, ‘You Can Say You Want A (Infinite) Revolution’ in Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle: Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With (North Adams: MASS MoCA, 2009). Bik van der Pol’s work contrasts the butterfly’s delicate ecosystem with the man-made intervention of a house famously situated on a flood plain, pointing to the work’s environmental impact. 39 Lisbeth Bik and Jon Van der Pol, ‘are you really sure that a floor can’t also be a ceiling?’ Bik Van der Pol, accessed on 20 August, 2020, https://www.bikvanderpol.net/162/are_you_really_sure_that_a_floor_cant_also_be_a_ceiling/. Peralta Lorca refused to consult a plan in constructing his Farnsworth House. 40 Pola Mora, ‘How an Artist Constructed a Wooden Replica of Mies’ Farnsworth House,’ Archdaily, August 21, 2017, https://www.archdaily.com/878665/how-an-artist-constructed-a-wooden-replica-of-mies-farnsworth-house?ad_medium=gallery. As a result, it inevitably differs from the original: failing to replicate the way a shelf in the bathroom forms a niche for firewood in the lounge. This rejection of plans and precision could be interpreted against the real lack of documentation for the Barcelona Pavilion and Wolf House. Through such critical deviations, these three projects draw out alternative narratives, telling stories that sit outside canonical history, and subverting the Modernist ideals that Mies espoused.

1:1 Models

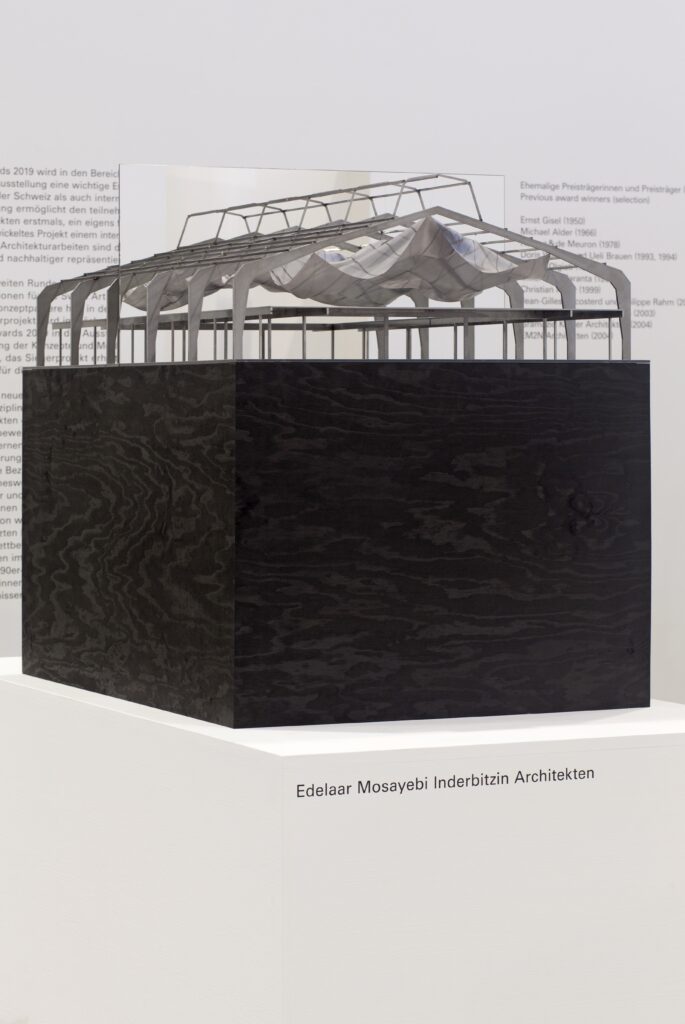

These installations sit firmly within artistic discourse, rather than architectural heritage, but recent self-professed 1:1 models have bridged between the two. Anna & Eugeni Bach’s mies missing materiality intervention in the Barcelona Pavilion covered its surfaces with white vinyl, intended to turn the pavilion into a 1:1 model of itself. 41 Anna Bach and Eugeni Bach, Mies Missing Materiality (Barcelona: Fondació Mies van der Rohe, 2019) Robbrecht en Daem’s 1:1 Golf Club Project, constructed an unbuilt golf club not far from its planned site in Krefeld, Germany. It, too, reduced Mies’ material palette, replacing marble and onyx with varnished plywood, while retaining the cruciform columns in stainless steel. In places where documentation was missing or contradictory, as in the rear elevations, the work broke down into standard stud framing without a roof. 42 See Christiane Lange, Mies 1:1: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe The Golf Club Project (Köln: Walter König, 2014); Maarten Liefooghe, ‘Tactically Ambiguous Performance: The 1:1 Model of Mies’s Krefeld Golf Clubhouse Project by Robbrecht En Daem Architecten,’ The Journal of Architecture 24, no. 3 (2019): 340-65; Ashley Paine, ‘Rethinking Replicas: Temporality and the Reconstructed Pavilion,’ in Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 34, Quotation: What Does History Have in Store for Architecture Today?, ed. Gevork Hartoonian and John Ting (Canberra: SAHANZ, 2017), 537-548.

This abstraction of materials is consistent with small-scale model making practices in architecture. Models are typically reduced to simple materials like card and balsa wood in order to emphasise form and concept, rather than approximate surface texture or detailing. Indeed, this interpretation of models has been part of architecture as far back as Alberti, who wrote: ‘[b]etter that the models are not accurately finished, refined, and highly decorated, but plain and simple, so they demonstrate the ingenuity of him who conceived the idea, and not the skill of one who fabricated the model.’

43

Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988), 35.

For Alberti, where this model becomes too gaudy, too noticeable as an interpretation, is the point when the craftsperson’s

work outshines the architect, and the model is rendered unsuccessful.

Despite their acts of material and spatial interpretation, Robbrecht en Daem did not claim to be authors or architects of the golf club. Almost echoing Alberti’s warning, the architects aimed to ‘reveal the “Miesian space.” We wanted to concentrate purely on the essence…an idea, previously given shape only in drawings, becomes a space that be experienced physically’. 44 Paul Robbrecht and Johannes Robbrecht, ‘Figures in a Landscape’, in Mies 1:1: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe The Golf Club Project, ed. Christiane Lange (Köln: Walter König, 2014), 104-106. Through their carefully selection and manipulation of elements, they offered a temporary experience of the architecture in place, almost as Mies intended. As Tegethoff writes, this particular site and climate were crucial in his original proposal. 45 Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 105-109.

The architects acknowledged their debt to Mies without exploiting this connection for polemical purposes or erasing their contribution by placing the construction in Mies’ oeuvre. Instead, they suggest another approach to reconstructive heritage, somewhere between replication and artistic installation. Like Alberti’s model-maker, they highlight the essential ingenuity of Mies’ ideas, even while quietly inserting their own ingenuity in expressing the gaps in that idea.

Simulated Signatures

Returning to Goodman’s autographic / allographic distinction can help us make sense of this complex interplay of authorships. Even if we accepted, as Neumann argued, that Mies’ original documentation is like a score—repeatable while remaining an authentic version—Goodman confirms two things that are worth noting here. First, the original score is still undeniably the work of composer, and all subsequent performances are associated with them. Second, ‘performances that comply with the score may differ appreciably …[but] a performance, whatever its interpretative fidelity…has or has not all the constitute properties of a given work.’ 46 Goodman, Languages of Art, 117. Goodman implies that, for a work to be recognisable as a ‘performance’ of an original, it must adhere to the vision of the composer, or architect.

Architecture has a long obsession with the architect’s signature, forging a link between the work and its designer that extends across time. 47 See Timothy Hyde, ‘Notes on Architectural Persons,’ The Aggregate Website, Oct. 15, 2013, http://we-aggregate.org/media/files/4d2504cf963089af4e12b5cf4b1eb2f4.pdf. Following Goodman, these Miesian reconstructions demonstrate that this signature cannot be scrubbed off, whether intended as heritage, art installation or 1:1 model. A similar sentiment can even be read in in Baudrillard’s profusion of simulacra. The hyperreal might simulate reality based on a referent that ceased to exist, but this illusion still requires that society holds onto its ‘old imagery’. 48 Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 13. A Miesian reconstruction—or Disneyland—plays a role in buttressing the original, even if it has long since lost its real authority.

What emerges from this survey is not how different each version is—how numerous their errors and seemingly-loose their interpretation—but how closely they observe Mies’ vision. The exchange with van der Rohe’s work, and with history, is not one-directional. Contemporary architects and artists do not simply exploit the original to enable their own interpretation. Instead, it reveals that Mies’ authority, and a canonical idea of his work, is necessarily present in all reproductions. Indeed, these artists and architects can only begin to add their own commentary by so closely aligning themselves with the original and by making their references visually legible. Ultimately, this exchange always reinforces Mies’ authority, just as the model maker has worked under the architect’s authority since before Alberti.

- Beatriz Colomina, ‘Mies Not,’ in Presence of Mies, ed. Detlef Mertins, (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 169.

- Although this passage appears in chapter 10, where Vitruvius discusses the use and construction of machines, he is clear that the models of machines he discusses were constructed by architects. Vitruvius, The Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Morris Hicky Morgan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914), 317.

- Mies began the project working as Peter Behrens’ assistant. In 1912, a first full-scale mockup was commissioned of Behrens’ proposal. Later that year, Mies left Behrens’ office and assumed the commission himself, constructing a second mock-up of his own proposal. See Detlef Mertins, Mies (London: Phaidon Press, 2014), 44-55; Franz Schulze and Edward Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography (Chicago and London: The Uiversity of Chicago Press, 2012), 37-43.

- Henry Thomas Cadbury-Brown, ‘Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in conversation with H T Cadbury-Brown,’ AA Files no. 66 (2013): 71

- Carsten Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe: The Built Work, trans. Julian Reisenberger, (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2014), 80.

- Hillel Schwartz, The Culture of the Copy: Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles (Cambridge, MA.: Zone Books, 2013). On the copy in architecture, see Ines Weizman, ‘Architectural Doppelgängers,’ AA Files, no. 65 (2012): 19-20, 22-24.

- Sigmund Freud ‘The “Uncanny,’ in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, trans. Alix Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press, 1919), 217-256.

- Mertins also reads a strong connection to Berlage’s geometry and Wright’s organic architecture. Mertins, Mies, 44-55; Paul Westheim, ‘Mies van der Rohe – Entwicklung eines Architekten,’ Das Kunstblatt, vol. 2 (1927), 56, quoted in Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe, 25; Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S M L XL (New York: the Monacelli Press, 1995), 63; Paul Goldberger, ‘Architecture: Mies Show at Modern’, New York Times, Feb. 10, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/02/10/arts/architecture-mies-show-at-modern.html.

- Wolf Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe: The villas and country houses (Cambridge, MA. and London: MIT Press, 1985), 58.

- Bergdoll called it ‘the first building in which Mies was able to bridge the gap between his commissioned work and his ideal projects’. Barry Bergdoll, ‘The Nature of Mies’s Space,’ in Mies in Berlin, ed. Terence Riley, Barry Bergdoll and Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2001), 87.

- See Bergdoll, ‘The Nature of Mies’s Space,’ 88; Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 58-59.

- See Gerrit Wiesmann, ‘A Push to Rebuild a Modernist Gem by Mies,’ New York Times, Mar. 21, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/arts/design/rebuilding-a-modernist-gem-from-mies-van-der-rohe.html; Anna Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork,’ Architectural Record, Apr. 21, 2016, https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/11624-scholars-debate-the-fate-of-a-lost-mies-masterwork; Robin Oomkes, ‘Recreating Mies’ Villa Wolf at Gubin,’ Dead Emperors’ Society, Apr. 10, 2016, https://deademperorssociety.com/2016/04/10/recreating-mies-villa-berg-at-gubin/.

- ‘Milestones,’ Mies van der Rohe Museum: Villa Wolf Gubin, accessed on August 20, 2020, https://cargocollective.com/villawolfgubin/Meilensteine

- ‘Reconstruction of the destroyed Villa Wolf (Gubin) by L. Mies van der Rohe,’ Fachhochschule Potsdam University of Applied Science, January 4, 2015, https://www.fh-potsdam.de/forschen/projekte/projekt-detailansicht/project-action/rekonstruktion-der-kriegszerstoerten-villa-wolf-gubin-von-l-mies-van-der-rohe/.

- Franco Stella, ‘Discussion about how to deal with the Wolf House in Gubin,’ Cultural Heritage Center, Brandenburg Technical University, 2016, https://www.b-tu.de/cultural-heritage-centre/diskussion/haus-wolf-in-gubin#c109435.

- Tegethoff, however, does note inconsistencies between elevations and plans, and difficulties in dating certain drawings. Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 58-59.

- Dietrich Neumann, ‘Visions’, e-architect, 21 May, 2017, accessed on 1 November 2020, https://www.e-architect.com/poland/wolf-house-guben-by-mies-van-der-rohe.

- Neumann, quoted in Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork.’

- Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrilll Company, 1968).

- Goodman, Languages of Art, 221.

- Schmidt quoted in Wiesmann, ‘A push to Rebuild a Modernist Gem by Mies.’

- Bergman quoted in Fixsen, ‘Scholars Debate the Fate of a Lost Mies Masterwork.’

- Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6.

- Neil Levine, ‘Building the Unbuilt: Authenticity and the Archive,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historian 67, no. 1 (Mar 2008): 14-17; Juan Pablo Bonta, An Anatomy of Architectural Interpretations: A Semiotic Review of the Criticism of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1975).

- For a detailed account of the intellectual, heuristic implications of this mirroring, see Mertins, Mies, 149-155.

- Robin Evans, ‘Mies van der Rohe’s Paradoxical Symmetries,’ AA Files, no. 19 (1990): 63– 64.

- Reich was artistic director of the German contribution to the Barcelona Exhibition but, as Colomina argues, it is an open secret that she also influenced Mies’ ‘radical approach to defining space by suspending sensuous surface’. Beatriz Colomina, ‘The Private Life of Modern Architecture,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 58, no. 3 (Sep 1999): 462-471.

- Jorge Otero-Pailos, ‘On self-effacement: the aesthetics of preservation,’ Place and Displacement: Exhibiting Architecture (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2014), 231

- See George Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces: Desiring the Barcelona Pavilion,’ RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no 39 (Spring 2001): 168-191.

- Schulze and Windhorst, Mies van der Rohe, 125. See also Jonathan Hill, ‘Weathering the Barcelona Pavilion,’ The Journal of Architecture 7, no. 4 (2002): 319-327; Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces’, 177

- Krohn, Mies Van der Rohe, 80. Mertins, however, cites the velvet curtain as part of Reich’s furnishings for the original pavilion. Mertins, Mies, 14

- Office for Metropolitan Architecture, ‘La Casa Palestra / Town Hall and Library, the Hague,’ AA Files, no. 13 (1986): 8-15.

- Koolhaas and Mau, S M L XL, 49.

- Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 12. Elsewhere in S M L XL, Koolhaas explicitly references Baudrillard. Koolhaas and Mau, S M L XL, 967. Both Levine and Dodds also raise the spectres of ‘Disneyfication’, simulacrum and Baudrillard in discussing the Barcelona Pavilion. Levine, ‘Building the Unbuilt’; Dodds, ‘Body in Pieces’.

- Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 13

- See Detlef Mertins, ‘Goodness Greatness: The Images of Mies Once Again,’ Prospecta 37 (2005): 112-121; Claire Zimmerman, ‘Photography into Building: Mies in Barcelona,’ Photographic Architecture in the Twentieth Century (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 49-83; Colomina, ‘Mies Not,’ 193-221.

- Howard Halle, ‘The best architects of all time, ranked,’ TimeOut, June 25, 2019, https://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/best-architects-of-all-time-ranked.

- Denise Markonish, ‘You Can Say You Want A (Infinite) Revolution’ in Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle: Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With (North Adams: MASS MoCA, 2009).

- Lisbeth Bik and Jon Van der Pol, ‘are you really sure that a floor can’t also be a ceiling?’ Bik Van der Pol, accessed on 20 August, 2020, https://www.bikvanderpol.net/162/are_you_really_sure_that_a_floor_cant_also_be_a_ceiling/.

- Pola Mora, ‘How an Artist Constructed a Wooden Replica of Mies’ Farnsworth House,’ Archdaily, August 21, 2017, https://www.archdaily.com/878665/how-an-artist-constructed-a-wooden-replica-of-mies-farnsworth-house?ad_medium=gallery.

- Anna Bach and Eugeni Bach, Mies Missing Materiality (Barcelona: Fondació Mies van der Rohe, 2019)

- See Christiane Lange, Mies 1:1: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe The Golf Club Project (Köln: Walter König, 2014); Maarten Liefooghe, ‘Tactically Ambiguous Performance: The 1:1 Model of Mies’s Krefeld Golf Clubhouse Project by Robbrecht En Daem Architecten,’ The Journal of Architecture 24, no. 3 (2019): 340-65; Ashley Paine, ‘Rethinking Replicas: Temporality and the Reconstructed Pavilion,’ in Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 34, Quotation: What Does History Have in Store for Architecture Today?, ed. Gevork Hartoonian and John Ting (Canberra: SAHANZ, 2017), 537-548.

- Leon Battista Alberti, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, trans. Joseph Rykwert (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1988), 35.

- Paul Robbrecht and Johannes Robbrecht, ‘Figures in a Landscape’, in Mies 1:1: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe The Golf Club Project, ed. Christiane Lange (Köln: Walter König, 2014), 104-106.

- Tegethoff, Mies van der Rohe, 105-109.

- Goodman, Languages of Art, 117.

- See Timothy Hyde, ‘Notes on Architectural Persons,’ The Aggregate Website, Oct. 15, 2013, http://we-aggregate.org/media/files/4d2504cf963089af4e12b5cf4b1eb2f4.pdf.

- Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 13.