Return to archive

title

Konvolut – Annotated Bibliography on Tacit Knowledge

suggested by

Eric Crevels Anna Livia Vørsel Mara Trübenbach Filippo Cattapan Claudia Mainardi Paula Strunden Ionas Sklavounos Jhono Bennett Caendia Wijnbelt Hamish Lonergan

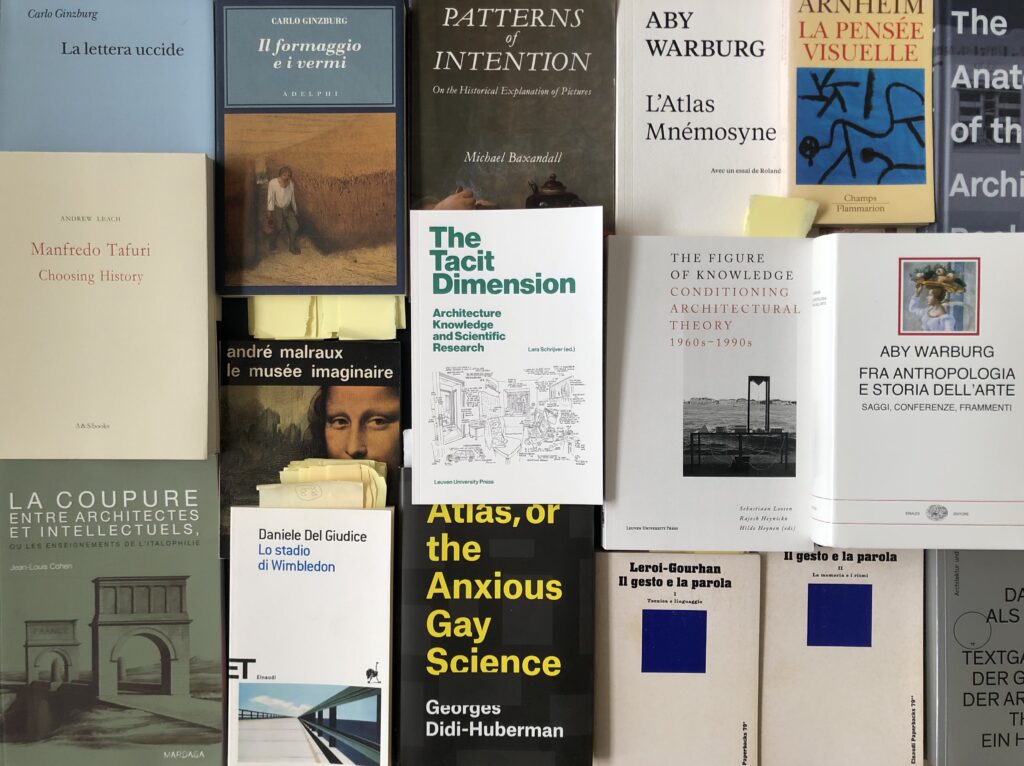

- Book Collection on Tacit Knowledge by Filippo Cattapan, Photo: Filippo Cattapan, 2023

- Book collection on Tacit Knowledge of Hamish Lonergan, Photo: Hamish Lonergan, 2023

- Book Collection on Tacit Knowledge of Jhono Bennett, Photo: Jhono Bennett, 2023

- Book collection on Tacit Knowledge of Mara Trübenbach , Photo: Mara Trübenbach, 2023

- Book Collection on Tacit Knowledge of Ionas Sklavounos, Photo: Ionas Sklavounos, 2023

Eric Crevels (EC), Mara Trübenbach (MT), Hamish Lonergan (HL), Anna Livia Vørsel (AV), Jhono Bennett (JB), Filippo Cattapan (FC), Caendia Wijnbelt (CW), Paula Strunden (PS), Ionas Sklavounos (IS), Claudia Mainardi (CM) compiled this bibliography with comments as part of the TACK Network training between 2019-2023.

Adamson, Glenn. “Manipulation”. The Invention of Craft. London: Bloomsbury, 2013, 1 – 52.

(EC) Adamson’s concept of “tooling” represents the framework of material objectsthat provides the infrastructure that allows other things to be made. It is particularly significant to study the production of architecture, allowing for an interpretation of building crafts as elements of the architectural “tooling”. It provides a foundational notion that can be extrapolated to include, apart from the material infrastructure, a set of techniques, skills and craft knowledge that support architectural production.

Adamson, Glenn. Fewer, Better Things: The Hidden Wisdom of Objects. New York: Bloomsbury, 2018.

(MT) This book contributes to the discourse of contemporary craft used and its backstory. The author claims the missingvalue of craft in people’s daily life. Craft might be only seen as an addition for something not as the active part for creating. It offers the context of material’s ethic as well as the network of people involved in the process of doing. Teamwork appears in many ways and not just in the main visible process of manufacturing and consuming.

Arendt, Hannah. “We Refugees.” The Menorah Journal (1943).

(MT) In 1943 the German-American philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt published in the Jewish-American magazine Menorah Journal an essay, entitled “We Refugees”. The essay describes the life story of “Mr Cohn”, who acts as a paradigm for Jewish immigrants and their struggle to integrate in their exile. Arendt argues that once Jews had left their home country, they became stateless. Without having any rights at all, they stay sentenced.

Becker, Howard S. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

(HL) At the beginning of Art Worlds (1982), Howard Becker announces that this is a sociological study, little interested in aesthetic theories. The key terms of his study are ‘art’ and ‘world’. A ‘world’ is formed through the cooperation of people engaged in some ‘joint activity’. In an ‘art world’, these people range from artists to printers and manufacturers to collectors, gallery directors and critics. ‘Art’ is one such ‘joint activity’, although Becker is ultimately little interested in defining art(s). Rather, he looks to how groups of cooperating people self-identify practices as art—or, conversely, reject the label—and what separates their specific type of art—photography, painting, presumably even architecture—from others. Rather than offering a functionalist theory—where relationships, institutions and organisations operate, relate and replicate in a predefined way—Becker’s ‘world’ is looser, showing how social systems survive even when reconstituted differently. According to Becker, art worlds use conventions to define their boundaries by mandating a basic level of knowledge required to consume and produce the art. Within an art world, increasingly specific conventions might be known only to some more ‘well-socialised’ members, requiring more refined knowledge that changes over time. Artists combine these recognisable conventions with variations to create new works. Artists and historians legitimise these new works by tying them to a selective lineage of ‘appropriate’ works from the past. The worth of this new art is then determined through the consensus of members of the art world, particularly those officials—gallery directors, critics, etc.—recognised by other members. What Becker calls ‘revolutionary changes’ come about when members of an art world are able to mobilise others—particularly those officials with authority—to accept larger innovations, and perversion of previous standards. Following Bourdieu, Becker concludes by acknowledging the way that conventional knowledge excludes people—based on ethnicity, age, sex and class—such that, while ‘mavericks’ might be accepted, ‘folk’ and ‘naive’ artists rarely enter an art world.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

(AV) “How does the agency of assemblages compare to more familiar theories of action, such as those centered around human will or intentionality, or around intersubjectivity, or around (human) social, economic, or discursive structures? And how would an understanding of agency as a confederation of human and nonhuman elements alter established notions of moral responsibility and political accountability?” p.21

Bhan, Gautam. “Notes on a Southern urban practice.” Environment and Urbanization, 31, no. 2, (2019): 639–654.

(JB) Bhan’s paper sets out the terms for how contemporary writers/practitioners are conceptualizing Southern Urbanism and how he is using these ideas to frame his own reading of urban ‘practice’ in Indian cities. In addition, he makes a call for a co-development of Southern Practice across the world and describes how important vocabularies are in this endeavor. The paper offers a polemic and didactic take on Southern Urbanist theory-building, while grounding the author in his context as a working example of his own call.

Carpo, Mario. L’architettura Dell’età Della Stampa. Oralità, Scrittura, Libro Stampato e Riproduzione Meccanica Dell’immagine Nella Storia Delle Teorie Architettoniche. Milano: Jaca Book, 1998.

(FC) Moving from Aquascutum raincoats and Serlio’s theory of orders, Carpo starts with this book his long-lasting analysis of the relation between architecture and technique. In particular, he identifies the invention of typographic printing as the first, substantial turn to mechanical production, deeply influencing the coeval architectural reflection and its further exportation in north European countries during the following centuries. Despite its strong technical underpinning, Carpo’s work appears to be first of all a cultural study on the specific modalities in which specific events can influence the overall mentality of the time and produce fundamental as well as unexpected transfers in between different disciplinary fields. Such a wide perspective on architecture will be crucially important for the possible meaningful insertion of postwar theories and practices in long term cultural and visual directions.

Chelkoff, Grégoire. “L’Ambiance sensible à l’architecture: paradoxes et empathies contemporaines.” in Ambiances in action/Ambiances en acte(s) – International Congress on Ambiances (Montreal: Réseau International Ambiances, 2012), 27-32.

(CW) Perceptual thinking, Plurisensorial attentiveness. In light of our contemporary context, architectural theoretician Grégoire Chelkoff suggests an investigative stance of thinking space by means of perception. Chelkoff highlights dimensions of the lived experience which may have gotten lost in normative, scientific approach to ‘ambiantal’ elements such as sounds, lighting, temperatures… He proposed looking beyond physical dimensions into their implications in the use of space, through a multisensorial lens. As an open-ended attitude, ambiance here embodies methodological aspects that call for attentiveness, being careful and letting go of some of the complex interrelations of spatial experiences which seem to some-times cloud our impressions. Time is hinted at as an important component to excavating potentials from a plurisensorial approach.

Collins, Harry. Tacit and Explicit Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

(HL) In this book, Collins argues that previous accounts of tacit knowledge were imprecise in distinguishing tacit knowledge from explicit, leading some writers to claim that all knowledge is tacit. Collins takes the opposite position, arguing that nearly all knowledge that seems to be tacit at first can be made explicit and that, paradoxically, it is explicit knowledge which is harder to explain and more rarely studied. He identifies an economic rationale in this focus on the tacit, particularly in management studies: tacit knowledge, transferable through verbal or written instructions, are cheaper to provide than the ongoing training (apprenticeships, practice, socialisation,) required for explicit knowledge. Following an analysis of explicit knowledge, Collins differentiates between three types of Tacit Knowledge: ‘These have to do, respectively, with the contingencies of social life (relational tacit knowledge), the nature of the human body and brain (somatic tacit knowledge), and the nature of human society (collective tacit knowledge)’ (x). ‘Relational’ tacit knowledge is the ’weakest’ form. According to Collins, this type of knowledge is ‘hidden’ either: because a group keeps it deliberately concealed from outsiders; or because the knowledge must be ‘read’ through study of an artefact; or because the knowledge resides in an individual or group with no need to communicate this knowledge to others; or through misunderstanding (person A tries to explain to person B, but does not realise that person B lacks a crucial piece of knowledge). Thus, Collins concludes that ‘relational tacit knowledge’ could be easily communicated if all these ‘contingencies’—of knowledge control or communication errors—disappeared. ‘Somatic’ tacit knowledge relates to the limits of the human mind and body. Here, Collins suggests that the way that we learn to ride a bike—taking Polanyi’s famous example—usually has little to do with reading or receiving instructions, but rather through a more unconscious and bodily process of internalising a skill. Crucially, for Collins such skills can be made explicit by reproducing the same actions through scientific study and recreate then with machines that can mimic the same processes, even if we have difficulty explaining exactly what we are doing. Collective tacit knowledge is, for Collins, the only ‘true’ tacit knowledge in that it can never be made explicit. This knowledge relates to the complex range of social competencies that vary by culture: in the case of riding a bike, these include knowledge of traffic regulations and customs of eye contact etc. Cross describes this knowledge as ‘polimorphic’, requiring different actions depending on the circumstances in a way that can only be learnt through socialisation and experience. Each individual’s knowledge of this communal tacit knowledge must be continually renewed against the standard of society, and in this way it resides in the collective and not the individual, making it impossible to communicate in a purely explicit way. In architecture pedagogy, this knowledge—about making socially-constructed decisions about the content of a drawing or design—is the hardest to communicate, residing in the architectural community as a whole, not just the individual tutor. In this way, it is a type of knowledge that might be said to extend beyond the studio to other seminars and types of media.In concluding, Collins argues that most human activity requires all three types of tacit knowledge in a way that is impossible to make explicit in machines.

(CW) Decomposing tacit knowledge. The author explores processes in order to create, cumulatively, a ‘map’ which could situate the forms of knowledge used in society. Such ‘mapping’ of terms and notions spanning from the explicit to the tacit, attempts to abstract and represent some of the many features of cognition.

Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost. “Introducing the New Materialisms” in Coole, Diana, and Samantha Frost, eds. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Duke University Press, 2010, 1-43

(AV) This text situates New Materialisms as a theory and methodology within a broader scope and argues for its contemporary relevance, a relevance that I would argue also extends to architecture. In their linking of a material engagement with political, economic and biopolitical questions, they articulate how nonsubjective structures (political economy and ideologies for example) are material in that they become inserted “into material practices governed by material rituals which are themselves defined by the material ideological apparatus from which derive the ideas of the subject.” Including a discussion around New Materialisms in architecture opens up questions around the dynamics and materializations of apparatuses within built fabric.

Cuff, Dana. Architecture: The History of Practice. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992.

(CM) The book offers an in-depth analysis of architectural practice culture –focusing specifically on the American context – as a “social construction”. It emphasizes the way tacit knowledge is able to disentangle the substance of a professional ethos –affecting both espoused theory and theory-in-use, and it concludes that the design process is based on collective actions as the result of negotiations within a social process.

Davidovici, Irina. Forms of Practice : German-Swiss Architecture 1980-2000. Zürich: gta-Verlag, 2012.

(HL) In this book, architectural historian Irina Davidovici deconstructs the monolithic myth of ‘swiss-German’ architecture between 1980 and 2000 through a series of theoretical propositions and case studies. For Davidovici, these practices and projects share certain tendencies that form part of a broader post-Postmodernist landscape of Swiss practice and theory, grounded in a particular formation of architecture imparted through the ETH Zurich and key publications like Archithese. Davidovici’s work is particularly useful in tracing the tendencies in education at the ETH, beginning with the architect-theorist Semper. She isolates a certain wariness towards theory, yet at the same time an insistence on explaining work through text. Particular attention is paid to the 1960s and 70s. Davidivoci connects many of the trends in swiss practice to these years: of autonomy, context/typology and the connections and disconnections between theory, writing and practices On a methodological level, Davidovici’s work is also useful. She begins with an introduction and general background to both Swiss culture and the specific architectural culture at the ETH, as the key site of training in German-speaking Switzerland. She then explores case studies, situating each building within its context: the firm’s output and theoretical writings; the place itself; relations to clients; broader historical/theoretical and aesthetic frameworks; and material construction. This is then followed by a series of thematic conclusions, which draw together elements form these case studies to make a wider case for a specific Swiss-German architecture.

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

(CM) The book points out that while social science possesses the ability to study the traditions, language, symbols, art and articles of exchange that make up a culture,it lacks a formal means by which to examine the ways in which people reappropriate them in everyday situations. The main purpose of this work is to make explicit the systems of operational combination which compose a “culture,” the tacit processes that organize the socio-economic order and the mediatic impact on the everyday.

(CW) De Certeau also highlights plural realities of our experience and perception of places. Unfolding multifaceted relations and back-and-forth between practice of space and place, he suggests the need for different tangible means of exploring tacit and perceptual phenomena.

Florenskij, Pavel. Die Umgekehrte Perspektive. Texte Zur Kunst. München: Matthes & Seitz, 1989.

(FC) Reflecting on Russian Icons and on the difference between perspective and reverse perspective (false perspective or non-perspective), Florenskij develops with this book a challenging iconological analysis of the cultural and ethical implications of representation, proceeding from Greeks and Romans to Middle ages and Renaissance, as well as ideally responding to Panofsky’s Die Perspecktive Als Symbolische Form published a few years before in 1924. As Panofsky, but from the opposite point of view, Florenskij relates representation modalities to technical aspects but also to the religious, social and political structures of the coeval historical contexts. Such an ambitious operation provides several meaningful arguments for the overall cultural understanding of European architecture and its historical development from the common background of classical architecture.

Forty, Adrian. “Of Cars, Clothes and Carpets: Design Metaphors in Architectural Thought: The First Banham Memorial Lecture”. Journal of Design History 2, no. 1 (1989): 1 – 14

(IS) The aim of Adrian Forty’s “Of Cars, Clothes and Carpets” is to show how architects and architectural theorists have systematically employed metaphors drawn from the field of design, as critical tools to engage in architectural debates. The key seems to be that design metaphors encourage a particular understanding of architecture as the result of human labor. In this manner, Forty examines three different theories of architecture which use different design metaphors, each one for its own purposes: John Ruskin, Gottfried Semper and finally a series of modernist metaphors of design, all reveal different understandings and assessments of the role of labor in architectural production. Finally, Forty’s attention is focused on dress, as a recurring design metaphor in architectural speech, most often to raise questions of appropriateness in relation to ornament. Thus, this text provides a methodological framework to explore how disciplinary knowledge is informed by the value systems and cultural contexts in which it is situated.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 1971.

(HL) In ‘The Formation of Objects’, Foucault applies a theory of discursive formation—developed in the previous chapter—to the ‘objects’ which constitute the discourse. He gives the example of psychopathology discourse from the 19th C, where new ‘objects’ emerge or are redefined rapidly: from concepts like hallucinations to practices like hypnosis. When they were first formulated, these ‘objects’ lacked a definitive meaning: they needed to be tied firmly to their definition or referent. Foucault asks ‘What has ruled their existence as objects of discourse?’ (Foucault, 41), before suggesting that their formulation could be traced in 3 ways. First, he points to the relationship between the emergence of surfaces, where the relationship of a field’s internal elements—how they are isolated, defined and connected—helps define its external limits that demarcate its domain’. Second these demarcations—in the case of madness and psychopathology—are established, defined and communicated in society through the authority of medical professionals, alongside legal and religious authorities (Foucault, 42). Finally, Foucault points to the grids of specification which establish the classification and differences between the different objects of the discourse (Foucault, 42). Foucault ultimately finds this tripartite explanation inadequate, failing to explain the actual emergence of the terms of discourse. Nevertheless, this explanation is useful in the context of tacit knowledge in explaining how the definition of these terms comes to be accepted and grasped by others. Read in this way, Foucault’s explanation suggests that Tacit Knowledge might be understood in two keys ways. First, that they are defined by establishing relationships between ‘objects’ (including practices, people and concepts) in a discourse. And second, that this definition is accepted by first acknowledging the authority of those individuals or bodies that proposed the definition. Yet, Foucault is clear that: “what we are concerned with here is not to neutralise discourse, to make it the sign of something else, and to pierce through its density in order to reach what remains silently anterior to it, but on the contrary to maintain it in its consistency, to make it emerge in its own complexity.” (Foucault, p47) In this way, discourse could be understood as a type of Tacit Knowledge; one which cannot be easily explained through signifiers or references, but which involves something less tangible and ‘anterior’. This ‘silently anterior’ quality of discourse cannot be faced head-one, instead, returning to Foucault tripartite explanation, it must be approached through the network of relationships between internal ‘objects’ of the field and by accepting the authority of those who establish the discourse.

Gell, Alfred. “Vogel’s Net: traps as artworks and artworks as traps.” Journal of Material Culture 1, no. 1 (1996): 15-38.

(EC) Alfred Gell’s overall discussion on the distinction of art and artifacts adds to the centuries-old discussions of aesthetics and functionality in architecture, challenging notions of what is represented in architectural spaces, the relevance of the intentions of its agents and how they are imprinted in the built environment (or not), and the relationship between architecture and other communities of practice – questions that are all the more pertinent when comparing ways of knowing, valuing and making in architecture and crafts. Moreover, his studies showcase how useful anthropology can be in discussions of aesthetics and practice or, more specifically, the questions of identity and meaning that permeate architecture and crafts.

Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture.” in The Interpretation of Cultures, 310-323. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

(CW) Thick descriptions, small concepts. Anthropologist Clifford Geertz leans on the notion of ‘thick description’ first put forward by Gilbert Ryle in the twentieth century, in order to formulate a semiotic approach to culture. He describes an interpretive stance to cultural analysis as the act of ‘sorting out structures of significations’, thus grasping/finding ones feet before relaying constructed readings. Thereby, culture becomes a shared context in which the meanings are probed, guessed, and reassessed —potentially thickly described. Individual interpretation as proposed by Geertz are of microscopic character: each refer to a specific instance in a particular context. Rather than cumulative readings expanding ethnographic knowledges, Geertz puts forward small interpretations and their inherent particularities as informants for future interpreting, through processes of ‘thinking and reflecting’. This approach gives importance to the underlying knowledges in any new attempt of uncovery. Moreover, in shaping his ethnographic methodology, descriptions deepened by layers of interwoven interpretative readings showcase a reflexive attitude towards unearthing knowledge.

Ginzburg, Carlo. I benandanti. Stregoneria e culti agrari tra Cinquecento e Seicento, Torino: Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1966

(FC) In this book, Carlo Ginzburg investigates the Friulian peasant mentality, cultural but also visual, in between the 16th and 17th century. He does it by referring to quite uncommon kinds of sources: the inquisitors’ reports which were produced during the trials to the Benandanti, members of a pagan-shamanic peasant cult based on the fertility of the land. These sources are very partial but disclose a substantially new understanding of the overall mentality of the time, which has been otherwise neglected and obliterated. A crucial assumption of the book is that research fields and correspond-ing methodologies are not universally fixed. On the contrary, the possibility to apply unusual methodologies could disclose unexpected and meaningful perspectives.

Gosseye, Janina, Stead, Naomi, Van der Plaat, Deborah. Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2019.

(MT) This book is a collection of twelve essays by an international group of scholars which deals with various research methods of oral history and the question of who has been unheard. The book critiques the way that architectural history contains mostly the main architect’s view as well as addresses only a particular group of intellectuals. Therefore the individual narratives within an on-going relational process should be decentralized by having an “integrative dialogue with actors”.

(CM) The book offers a different position towards oral history, theorizing the radical potential of a methodology that has historically been cast as unreliable. Looking at different topics, from the role of anecdote to oral testimonies. In general, the authors call for a renewed form of listening to enrich our understanding. Even if the books mainly refers to buildings, what they do, and what they mean to people, it can represent a useful methodological reference especially for those researches that can’t relate to conventional sources.

Groupe μ. “Douze Bribes Pour Decoller.” Collages. Revue d’esthétique, no. 3–4 (1978): 11–41.

(FC) The Groupe μ, a multidisciplinary collective based at the University of Liège, was invited in 1978 to curate a special issue of the Revue d’Esthétique. The chosen topic, collages, has been addressed as a specific form of rhetorical construct – être rhétorique –, according to the linguistic and semiotic framing defined by the group with their book Rhétorique Générale published in 1970. The group substantially analyzed the production of meaning which is possible to achieve by way of composing elements together in the form of collages. The crucial importance given to the technical aspect of such compositions, in particular in relation to the different degrees of isotopy that different techniques make possible, is a crucial reference for the research project.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575.

(AV) Donna Haraway asks: what counts as knowledge? And who has the agency to claim it?

(IS) In this article, Donna Haraway delves into the relationship between feminism and science through the notion of objectivity, which she critically revisits and reclaims. By the same token, Haraway also claims back the metaphor of knowledge as vision. Even if there are good reasons why one-point perspective has historically been associated with the detached objectivity of modern science and the authority of the knowing subject over the world, a feminist writing of the body needs to “reclaim that sense” Haraway tells us. Starting from an insightful critique of what she calls ‘radical social constructivism’ she arrives at a redrafting of Sandra Harding’s plea for a “successor science” in which ethics and politics ground scientific and epistemological discussions. From an architectural point of view, what is particularly interesting in such a reasoning is that “a corollary of the insistence that ethics and politics provide is granting the status of agent/actor to the “objects” of the world”: Situated knowledges require that the object of knowledge be pictured as an actor and agent, not as a screen or a ground or a resource, never finally as slave to the master that closes off the dialectic in his unique agency and his authorship of “objective” knowledge.

It is this parallel emphasis on the ethical dimension and the world as an ‘active agent’ that I am interested in further exploring, and combining with different yet related discussions. For example, could such an emphasis be read next to Alva Noë’s Biology of Consciousness, which stresses the fundamental role of the world in the structuring of experience?

Harries, Karsten. The Ethical Function of Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000.

(IS) In this book philosopher Karsten Harries approaches architecture primarily as “a way of articulating a common ethos (…) a way of standing in the world”. In this sense, architecture is understood as a kind of ‘poetic’ interpretation (poíēsis: the process of making; production, creation) of the diverse and often conflicting cultural values of human societies; an interpretation that is carried out through the practice of building. Importantly, as this interpretation takes place it becomes an operative part of the world, in a silent, tacit way. Harries develops his theory by tracing the historical under-pinnings of two cultural and intellectual attitudes, which he identifies as the ‘ethical’ and the ‘aesthetic’ approach in art and architecture. Through such a prism he carries out a thorough examination of major areas of architectural discourse such as Ornament, Representation, Temporality, and Community, thus offer-ing a valuable framework for a research on the tacit links between architectural knowledge and its cultural contexts.

Ingold, Tim. “The Textility of Making.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (2009): 91–102.

(EC) Ingold’s Textility of Making summarizes his distinction between hylomorphic and textile ways of making, and show their direct presence in historical ways of thinking and making architecture – both of which are important for researching the starting point of divergence between contemporary architecture and crafts that traces back to their common background.

Kockelkorn, Anne. “Uncanny Theater. A Postmodernist Housing Play in Paris’ Banlieues 1972–92.” in Productive Universals—Specific Situations. Critical Engagements in Art, Architecture and Urbanism, 336 – 381. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019.

(MT) The architect and author Anna Kokelkorn writes a theatre play of an ethno-graphic study that studies the development of Paris’ Banlieues within a period of six months and around 50 interviews. It confrontsthe memories of the first inhabitants of “Espaces d’Abraxas” by the spanish architect Ricardo Bofill in 1982. The theatre play is set in three acts and has three different speaker groups. Kockelkorn provokes the contrast between the outsiders and inhabitants when setting up relations between various speakers, for and against. The written piece aims to show how the urban gets completely fragmented through the environment and the embedded transformed abraxas over time.

Krauss, Rosalind. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” October 8 (1979): 31–44.

(HL) Krauss begins this essay by noting that in post-war art, the category of ‘sculpture’ had come to encompass a range of almost contradictory works. Art criticism tended to explain this diversity through historicism; linking ‘vanguard aesthetics’ to familiar precedents, despite frequent contradictions between the new works and their supposed ancestor. Indeed, these connections stretched the term ‘sculpture’ to such a degree that it began to lose any meaning. Yet Krauss famously notes ‘that we know very well what sculpture is…it is a historically bounded category and not a universal one.’ She links this ‘category’ to the site-specificity of the monument with a pedestal. Nonetheless, this logic was transformed under Modernism, becoming site-less and subsuming the base into the sculpture itself. By the 1960s it became easier, according to Krauss, to define sculpture through its inverse: whatever is in the gallery that is not-architecture, or outdoors that is not-landscape. Krauss uses these terms to establish a Klein Group expansion diagram, establishing an ‘expanded field’ of practices related to sculpture that emerged in the work of several artists around 1968-70. These practices include ‘marked sites’ (Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson, 1970), ‘site-constructions’ (Partially Buried Woodshed, Robert Smithson, 1970), and ‘axiomatic structures’ (Sol LeWitt, Richard Serra). It is this ‘expanded field’ that characterizes postmodernism, providing a framework for artists to move across media without contradiction. Krauss concludes with the suggestion that her essay could be considered a general methodology, not just a study of a specific art-historical period. Rather than thinking about art through precedents, Krauss’ approach interrogates the causes of the change, posits the existence of ruptures in artistic genealogy, and emphasizes the importance of logical, diagrammatic analysis.

Latour, Bruno, Yaneva, Albena. “Give me a Gun and I Will Make All Buildings Move: An ANT’s View of Architecture.” in Explorations in Architecture: Teaching, Design, Research, edited by Reto Geiser, 80-89. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2008.

(MT) In this essay, the philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour and sociologist Albena Yaneva address the architect’s limited ability to see the building’s motion and its decentralization by likening it to Etienne Jules Marey’s “photographic gun”. The authors stress the need in architecture to integrate a theory that captures the continuous flow of the “moving project”.

(CW) Setting architecture in motion. This approach brings to attention a plurality of dimensions that are unfolding throughout conceiving, building, and using spaces, in constant acts of transformation. It also probesaspects of an ‘architect’s tacit knowledge’ lying somewhere between his ‘mind’s eye’ and physical matter, shedding light on creative expressions such as models and drawings as stimulus to the haptic imagination, and perhaps opening paths to new design strategies.

Levi, Giovanni. “On Microhistory.” in New Perspe., edited by Peter Burke, 97–119. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

(CM) According to Giovanni Levi, one of the pioneers of the approach, it began as a reaction to a perceived crisis in existing historiographical approaches. The most distinctive aspect of the microhistorical approach is the small scale of investigations. Microhistorians focus on small units in society, as a reaction to the generalisations made by the social sciences which do not necessarily hold up when tested against these smaller units. 21

Mareis, Claudia. “The Epistemology of the Unspoken: On the Concept of Tacit Knowledge in Contemporary Design Research”. Design Issues 28, no. 2 (2012): 61–71.

(AV) In her text, Claudia Mareis situates Polanyi and tacit knowledge really concisely as a bodily, situated form of knowing: “Polanyi supports his statements on Gilbert Ryle’s differentiation between ‘knowing that’ and ‘knowing how’ and presents human expertise correspondingly as a form of practical know-ledge. He thereby develops a knowledge and consciousness theory concerned not with a static knowledge result (knowledge), but withthe act or the process of recognition and perception (knowing); he therefore assigns the human body and its senses a central position in the production of knowledge.” p.65

(HL) In this essay, design scholar Claudia Mareis argues that tacit knowledge is created by social and discursive mechanisms. She frames this position in opposition to existing attempts to understand tacit knowledge—and related terms like Cross’ ‘designerly way of knowing’, ‘experientialknowledge’ or ‘situated cognition’, emphasizingthe practical and personal—that frame tacit knowledge and design in general as a ‘natural’ phenomenon. Instead, Mareis turns first to Polanyi, who identified not just theoretical and practical knowledge as tacit, but also knowledge that is ‘influenced by moral, cultural, and scientific authorities…realized within the social boundaries generated by them’ (66). Indeed, Polanyi’s writing on ‘expertise’ and ‘connoisseurship’—transferred through tradition and authority, for example through master-apprentice relationships—are frequently missing from existing accounts in design studies. Mareis then links these socially constructed qualities to Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’, comprising ‘all the habits, customs, physical abilities, aesthetic and cultural preferences, and additional non-discursive aspects of knowledge that are considered self-evident to a specific group’ (68-68). In this way, tacit knowledge in design transfers and reinforces these same social relationships and exclusionary social capital in a non-verbal way. In seeing this process as ‘natural’, researchers assume that the knowledge cannot be made explicit when, instead, some knowledge is kept deliberately tacit to support power structures: here she turns to Foucault, and his notion that ‘discourses are always cultivated by certain taboos and speaking bans’. Mareis’ account is one of only very few accounts in design studies of the social dimension of tacit knowledge, and is particularly useful in confirming suspected links between Polanyi and Bourdieu.

(CW) Tacit knowledge in the theory and practice of design. Claudia Mareis hints at a bridge between research in the fields of tacit knowledge and practice in design. She questions where design knowledge is located, beyond verbal layers, to understand how design research has evolved to integrate tacit knowledge as a grounds for further investigative approaches. Through her view of this overall growing field of design approaches, Mareis suggests the importances of an awareness of the social dimensions of knowledge, as an active component of research which allows the questioning of findings.

Moravánszky, Ákos. Competing Visions: Aesthetic Invention and Social Imagination in Central European Architecture 1867-1918. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998.

(IS) Through a comparative analysis of pioneering projects by leading architects in Central Europe in the time of the Austro- Hungarian monarchy, Ákos Moravánszky discloses how these are informed by different cultural values and how they stand for competing inter-pretations of modernity. The cities of Vienna, Prague and Budapest around which Moravánszky centers his research serve as advantageous case studies for exploring architectural knowledge in different yet similar contexts; as well as to appreciate the significance of the larger cultural context provided by the multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire. But what is equally interesting is that Moravánszky draws attention to a geographical and cultural entity which, until that point, had not been systematically addressed ‘as such’ by the history of architecture. In doing so, he also demonstrates that “the relation of architecture to its social environment cannot be described without challenging established historiographical concepts.”

Noë, Alva. Out of Our Heads : Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness. New York: Hill and Wang, 2010.

(IS) Questioning the well-established hypothesis that considers the brain as the locus of consciousness, philosopher of mind Alva Noë presents an alternative approach that situates the emergence of experience between the living organism and its environment. His central claim is that the ways in which human experience and consciousness are constituted ought to be searched not (only) inside the human brain but in the dynamic integration of the human being in its surrounding world. This integration, Noë says, should be thought of as an action that is performed by living organisms in dialogue with their environment: experience and consciousness are “enacted with the help of the world.” Thus, his view is described as an enactive or ‘actionist’ approach, according to which seeing or hearing is not something that happens in us, but rather something that we do — human sentience is to be understood in terms of skill, habit, and practical knowledge. Moreover, this approach emphasizes the multi-sensory nature of this skillful interaction, in which our senses do not act separately in isolation but rather in close interdependence. By presenting different phenomena of neural and perceptual plasticity, Noë arrives at a description of the senses as “multimodal styles of exploration of the world,” and as sensorial modalities. Importantly, this multimodal exploration also strongly depends on the presence of others: the social and cultural interaction that takes place within (more than) human communities. By insisting on the enactment of human perception “with the help of the world,” Noë invites us to reflect on the significance of cultural landscapes and built environment, the role of architecture and the city in the life of human consciousness. Thus, he also seems to offer new ways of reading the various traditions of architectural theory. Such a use of Noe’s thought may be found in Attunement (MIT Press, 2016) by Alberto Pérez-Gómez:

“Alva Noe’s work allows us to understand how the traditional view of perception operative in all premodern architectural theories (one that was “musical” and primarily synesthetic, and that espoused harmony as a central architectural value), is vindicated by the recent understanding of the senses as “modalities” that transgress their functional boundaries and defy any exclusive association with the physical organs to which they have been conventionally attached.”

Ockman, Joan. “Between Ornament and Monument. Siegfried Kracauer and the Architectural Implications of the Mass Ornament.” Thesis no. 3, Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Bauhaus-Universität Weimar (2008): 75–91.

(IS) “How do urban phenomena mediate lived experience and historical knowledge? In what sense can the city be said to have a collective psyche or unconscious?” The answers to such questions posed by thinkers as Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer, Joan Ockman says, imply different conceptions of the built environment as a medium of consciousness. From such a starting point, Ockman revisits the notion of “mass ornament” introduced by Siegfried Kracauer in the 1920s through the lens of his ideas about architecture and the city and historicizes the concept as a prefiguration of The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord. More specifically, Ockman’s attention is focused on how Kracauer, unlike most of his colleagues of the Frankfurt School, treats mass culture and its ornament as a multivalent medium with which critical thinking and artistic creation should ‘work with’ if they are to truly engage with the cultural tensions that permeate the Modern Era. By presenting the antinomies that lie in the heart of Modernity, the mass ornament seems to allow for a deeper understanding of the modern predicament and thus opens up the possibilities of its transcendence. Within such a framework, Ockman examines Busby Berkeley’s “Gold Diggers” (1935) and Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” (1935) as two different expressions of the mass ornament: as ‘popular entertainment’ in capitalist society and as ‘solemn ritual’ in Nazi propaganda. Following Debord, she analyzes the two films in terms of “diffuse” and “concentrated” spectacle and then describes how during the 20th century these competing forms have converged into the form of “integral spectacle.” Building on this notion, she finally examines two architectural projects of the 21st century showing how the ‘mass ornament’ may be used as a critical device to discuss contemp-orary architecture’s spectacular culture.

Panofsky, Erwin. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1939

(FC) In the introduction of the book, Panofsky set one of the most effective and long-lasting framing of Iconography and Iconology, which he developed within the field of Renaissance studies. The synoptic table that he introduces, the same one to which he will go back also in his Meaning of the Visual Arts in 1955, articulates the analysis of the artistic object into three main phases: pre-iconographic description (or pseudo-formal analysis), iconographic and iconologic analysis, which respectively address three different aspects of the work of art (the natural, the conventional and the intrinsic) and which contributes to the definition of three parallel histories (the one of styles, the one of types and the one of symbols). Still nowadays, such interpretative structure arises as a very effective research frame, which furthermore allows for the incorporation of the most recent reflections in the field of art history.

Rendell, Jane. Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

(JB) The introduction to the author’s positional body of work, sets the theor-etical and intellectual context for the ideas underpinning Site-Writing as a practice and their aims in giving voice to this form of practice. The author uses seminal writers on psychology, art-practice and philosophy as figures to guide their later theories and discusses the relation-ship between architecture and art-critique as reflective and positional practices.

(AV) “Site-Writing explores the position of the critic, not only in relation to art objects, architectural spaces and theoretical ideas, but also through the site of writing itself, investigating the limits of criticism, and asking what is possible for a critic to say about an artist, a work, the site of a work and the critic herself and for the writing to still ‘count’ as criticism.” p.2

Ricoeur, Paul. “Action, Story and History: On Re-Reading The Human Condition”. Salmagundi, no. 60 (1983): 60-72

(IS) This article by Paul Ricoeur presents a particular reading of Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (1958), less as a work of political theory as it is usually the case, and rather from a point of view closer to philosophical anthropology; in order to examine what he calls “the most enduring features of the temporal condition of man.” The reason for such a reading, Ricoeur says is “to vindicate the strategy of the author,” i.e. the use of ancient categories such as poesis and praxis, to address cultural phenomena of this day and age. In this manner, Ricoeur structures his inquiry mainly around the threefold distinction of Vita Activa into Labor, Work and Action, while his main point of focus is the link between Action and the notions of Story and History. In this way, inner relations between the three categories of the Vita Activa are revealed, such as the role of Work as a document and monument of Action. Finally, through this temporal reading of Arendt’s conceptual framework Ricoeur also explains different understandings of History in antiquity, the middle-ages and modernity, and points to the cultural significance of (not) distinguishing between what we consume, what we make and what we do.

Roberts, Bryony, ed. “Expanding Modes of Practice.” Log 48 (2020).

(CM) This thematic Log issue edited by Bryony Robers focuses on how the most evident challenges of the current societal shift, such as an increased awareness of equality at large –with a particular attention towards the role of women and minorities–, a search for alternative solutions to globalization, and a critical take on the environment and technology after the optimism that had characterized the beginning of the new millennium, are the preoccupations that inform the current architectural discourse.

Robert, Frančois, ed. Ecrire l’Histoire Du Temps Présent. Paris: CNRS, 1993.

(CM) The history of the present times was born following the Second World War. Depending on the country, the notion does not have exactly the same meaning. This book, as representative of the French history of present times reveals the fact that the history of present times is a specifichistory, different from the others because it is closer to the social sectors rather than to other historical periods. Given the recent timeframe of my research –focusing on the last 20 years, from the year 2000 onwards,– the history of present times represents one of the main theoretical and methodological references.

Schuppli, Susan. Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020.

(AV) Susan Schuppli iterates the operative concept of the ‘Material Witness’ as one that explores the evidential role of matter. The operative concept is situated within the generalfield of New Materialism but aims to radical-ize the political relationship between materials and the act of witnessing and giving testimony.In her work, Schuppli explores materials registering external events and exposes the practices and procedures that enable the material to ‘speak’, to bear witness. Throughher work, the materials then make visible the registered events as well as the methods and epistemic frameworks in which they are broughtinto being or exist within. Materials: nonhumanentities and machinic ecologies, become ‘Material Witnesses’ in their act of giving testimony, “when the complex histories entangled within objects are unfolded, trans-formed into legible formats, and offered up for public consideration and debate.” (p.18) In bringing in this operative concept, Schuppli questions the processes in where meaning is bestowed onto things, what legitimate acts of witnessing are, structures of knowledge production and validity of different forms of knowing. “Apprehending materials as dynamicand expressive witnesses rather than inert and mute bystanders is achieved not only by means of the specific probes or techniques that can be brought to bear upon them in order to exhorttheir testimonials and, by extension, the discursive frameworks that have been sanctioned to translate their material encodings into actionable events. It also results from being compelled to reflect upon the limits of our own experience and knowledge.” (p.308)

Tattara, Martino. “Drawing Lessons from Aldo Rossi’s Pedagogical Project.” OASE 102 (2019): 62–70.

(HL) In this essay, Tattara frames Aldo Rossi’s pedagogy at Politecnico di Milano (1968-71) and ETH Zurich (1972-75) as a synthesis of theoretical and practical design approaches in the non-hierarchical pursuit of a common research project, involving students, assistants and professor. For Rossi, it was important to impart lessons on conceiving architecture—which might be characterised as Tacit Knowledge—through multidisciplinary readings, lectures and detailed analytic and descriptive drawings of the city. Rossi approach, therefore, was radical in emphasising approaches and ways of thinking about architecture rather than fully formulated design projects. While Tattara emphasises the democratic nature of this approach, Rossi nonetheless occupied a position of strong authority, especially given his preference for lectures over tutorials. Arguably it was this position of authority which allowed him to impart these approaches to architectural tacit knowledge.

Vesely, Dalibor. “The Situational Nature of Communicative Space.” in Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation, 87 – 93. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006.

(IS) This passage is drawn from Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation (2006) and more specifically from the 2nd chapter on “The nature of communicative space,” where Vesely presents some of his central concepts for his theory on the ‘continuity of meaning’ in architecture. More specifically, here Vesely arrives at a first outline of the question on “the conditions under which representation takes place.” This he does by mainly focusing on the notion of language, which we are asked to consider not merely “as an explicit and self-sufficient mode of verbal communication” but in a much broader sense as a constituent element of culture itself. The key here seems to be the degree of communication between a non-verbal, tacit substratum, explicit verbal expression and the articulation of ideas; or between what he calls ‘lower’ and ‘higher’ levels of perception. This communication, which “rests largely on the metaphorical nature of human experience” is presented as a presupposition for continuity of meaning to be achieved. A way to move deeper into the question of communication between such different levels may be found in a certain understanding of geometry, as a mediation between concrete and abstract, visible and invisible realities – and further on, by delving into the role of symbols in human cultures. Later in his book, Vesely summarizes this point, with a strong parallel emphasis on the tacit dimension:

“In earlier discussions of the situational structure of the natural world, I noted that the world is articulated primarily on the prereflective level and in the spontaneity of our “communication” with the given phenomenal reality and cosmic conditions. Communication itself has no identifiable origin. It takes place in a world that is already to some extent articulated, acting as a background for any possible communication or interpretation. Most important, communication is always a dialogue between the new possibilities of representation and the given tacit world, described in modern hermeneutics as an effective history (Wirkungsgeschichte). The tacit world is never fully accessible to us. Always to some extent opaque, it can be grasped or represented only through its symbolic manifestations.”

Wagner, Roy. The Invention of Culture. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1976.

(EC) Wagner’s account of the invention of culture shows the importance and potentiality of using ethnographic methods to discover one’s own culture through the understanding of others. Moreover, his notion of “cultural relativity” implies the equivalency of different cultures – by understanding culture as an epistemological tool for investigation, one can assume different communities of practice can be investigated as cultures of their own: for example, those of crafts and architectural production.

van Eck, Caroline. Classical Rhetoric and the Visual Arts in Early Modern Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

(FC) In this book, Caroline van Eck studies the crucial role of Classical rhetoric in shaping the artistic and architectural production starting from the European Renaissance. The theory of rhetoric is not considered only as a set of rules aimed at convincing interlocutors but as a primarily important design tool. In particular, architectural rhetoric is addressed in relation to the construction of a shared past or cultural memory, even if substantially fictional. To this extent, the early Italian treatises by Serlio and Scamozzi are analyzed in relation with the substantial influence they had in England, from Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren to John Soane. The analysis is conducted in parallel and in close relation with the coeval artistic prod-uction and opens towards the crucial impor-tance of Aristotelian philosophy in the definition of certain specific visual practices.

Vladislavic, Ivan. Portrait with Keys: Joburg & what-what. Johannesburg: Umuzi, 2006.

(JB) The book is described as a “guide to Johannesburg, that is not a guide”. By using a non-structured narrative style, the author de-constructs and fragments a series of ‘portraits’ of everyday life in the city and weaves them together under loose chapters, key places and domestic objects (the collective what-what). The disconnected and fragmented structure of the stories, their own abrupt starts and ends as well as the iconic book cover (the moment of demolition of a early 20th century ‘skyscraper’) suggest an interpretation of Johannesburg (and many other large urban areas) energy and metabolism.

Yaneva, Albena. Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2009.

(CM) This book presents an ethnographic account of the design rhythm in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in the early 2000s. Written in first person to reinforce its journalistic nature, it allows a close-up glance made of observations, reflections, interviews, anecdotes, images, data, diagrams and vignettes, giving a tangible feeling of the working environment of the investigated office. Such close-up analysis resemble micro-histories that, by looking at the everyday practice, intend to identify the characteristic methodology of the office and the agency it is capable of producing.

(HL) Consistent with the Material Turn, Yaneva argues that architectural practice should be considered through precise, anthropological study of practices and materials within an office, rather than through the abstract theories of critical studies. Through interviews and observations, Yaneva argues that there is no distinctive OMA style, but instead a way of working through models and books, obsessively evaluating the effectiveness of particular solutions and the reworking of old, with this revisiting constituting the thread that links various projects together. Yaneva also suggests that it is observation of these models and books—displayed in the middle of the office—that introduces new arrivals to the processes of design in the office in a way that could be characterised as a transferral of tacit knowledge. Yaneva’s account introduces a series of moments of judgment, where designers evaluate models and diagrams as successful or not—variously described as interesting, grotesque and beautiful—by the standards of the office and the discipline.

(CW) Through her unconventional approach to studying an architectural office from the inside out, Albena Yaneva opens up new routes and possibilities for design research. Deliberately stepping outside a broader, more theory-led research framework, Yaneva gives attention to experiential aspects of the design practice which can easily be overlooked, as they may be part of an office’s basic working modes. She opens up roads to new research stances by attempting to narrate and give a glimpse into the ‘small’ design actions and activities which dimly play into what an office eventually sets out into the world.

Yaneva, Albena. Mapping Controversies in Architecture. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2012.

(CM) The author argues that to understand a building it is necessary to understand the intersection of forces –from political to natural and from real to metaphorical ones– that generated it. Following the STS method, within chapter 2 the author reflects on the relation between architecture and society, arguing that the key to understanding the built environment lays with due comprehension of the society and culture in which it exists.

Zaera-Polo, Alejandro. “Well Into the 21st Century: The Architectures of Post-Capitalism.” El Croquis, no. 187, (2016)

(CM) The article is an attempt to define and categorize new forms of practice that have emerged in the last decade through a synoptic method deeply inspired by Charles Jencks’ Evolutionary Tree diagram. The article represents an important tool of research and mapping. In the attempt to express, name and list design processes that belong to an implicit domain of knowledge, Zaera-Polo explains the differences in visions between them, representing for me an important intuition in order to decodify contemporary practices.