Return to archive

title

Scale in passing: Re-calibrating narrowness through spatial interventions

authors

Mara Trübenbach Marianna Czwojdrak

Abstract

Reflecting on the art installation Motion of Scales, which was temporarily installed in the city centre of Kolding, Denmark, as a part of the NORDES 2021 conference, this article explores the interrelation between body, material and its performative potential. Analysing the design process through description and observation of how it was experienced and interacted with by urban public, the design-led research aims to interrogate subjectivity, emotion and embodied knowledge in academic research and its methods. How could movement within scale open up new perspectives? Does material hold a potential to reveal new modes of thinking in design research? How and to what extent could emotion contribute to design practices?

Proposing

It is a hot summer. We, that is: Marianna, a Polish designer and researcher and Mara, a German architectural designer and researcher, are on the second floor at the Bauhaus building in Dessau. The reason for this accidental encounter is having been selected for the ‘Bauhaus Lab 2019’, an interdisciplinary research project by The Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. 1 The authors were among eight selected professionals for the Bauhaus Lab programme at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation in the summer of 2019, Dessau (DE), where they collectively curated the exhibition “Handle with Care: Unpacking a Bulky Table.” Each year the postgraduate programme addresses a different modern design object from the Bauhaus heritage and this year we are set to investigate a BT3 table designed by Marcel Breuer in 1933 and to uncover actors and networks involved that had been overseen in the past. While we work in an interdisciplinary team with backgrounds ranging from graphic, architectural and curatorial design, we both realize that the exchange between research and visual capabilities is of great value for the understanding of design history and theory. Such practice-based research is a phenomenon of combining alternative research methods with our great interest in aesthetics which we would like to explore and practise further beyond the Bauhaus Lab as an interdisciplinary duo.

Two years later we came across an open call from NORDES 2021 conference. Reading about its year’s theme, matters of scale, we immediately recalled our summer at the Bauhaus when the spirit of modern history and state-of-the-art glass facade led to mixed feelings and the thermal confusion of our bodies due to the heat wave while functioning, for what it is worth, in a glasshouse. During the stay in such an iconic venue we realized that the scale of a body is not solely linked to the size of a building but to its material, body temperature and even clothes we wore as well but in particular to the physical movement and emotional reaction of bodies within the space. On the one hand, when it was hot (plus 30 degrees), we were spread across the whole room as each of us needed space. We embarked on a cross-ventilation adventure, but the room turned out to be too huge and almost impossible to cool down. Normally, when the temperature was bearable, we did not even notice the scale difference between the room and our bodies. That circumstances of movement and weather conditions paired with physical and emotional body reactions became key to the design proposal we submitted in January 2021 (see Figure 1) accompanied by this motivation:

Motion of Scales seeks to challenge the embodied knowledge of scale of passers-by and to rediscover the Narrow Path through new spatial calibrations. By creating an optic fissure between two peaks (buildings) and amplifying its density, Motion of Scales seeks to prompt fleeting memories and perhaps vague feelings, in order to shed a new light on a common space, hidden in the city centre of Kolding. As a temporary site-specific experiential design installation, Motion of Scales plays with perceptions of narrowness and attempts to open up dialogues on matters of scale and possibly elicit yet unknown layers of scale.

(Czwojdrak and Trübenbach 2021)

When scale is associated with movement, it immediately implies that we need to recalibrate our understanding and to break patterns we have been

used to. According to Ole B. Jensen, ‘to scale’ is ‘processes of becoming and doing’ (2021: 43), constantly moving between volume and relevance. If we now assume that scale is information rather than a hierarchical order that tends to ignore relations, then the new knowledge gained shifts with and in scaling, opening up new perspectives. Scale should no longer be seen as an ultimatum, but rather as a companion to find new modes of thinking. In such an approach, the material acts as a tool to create an ever-changing experience over which one has no control, but is put in a position of choice: to trust and engage with – or to fear and withdraw from the process. Therefore, understanding scale is as much a matter of physical experience, as of mental perception. Similarly, to the practice of architecture, we believe that emotions play a crucial role in how we approach space in general: how we act towards, approach and behave in it. However, it is rather a reaction in hindsight than a factor during the design process and we were interested to examine how it could become a part of the research through design methodology. Recalibrating the correlation between body and its performative potential meant that the site we had chosen for our installation became a stage for observation and, more importantly, for experiencing ‘scale in motion’.

Fig. 1: Elevation of the project proposal.

Researching

Since the very beginning, we were interested in reworking the common perception of scale as a fixed state: a universal, ‘measurable’ reference that is same for everyone. What we found missing in such an understanding of scale are essential factors for any design process traditionally oriented to producing a solution (spaces, products and services): human agents, subjective interpretations and outside conditions. Architects and designers aim to design for different users (who are of certain age, background, ethnicities, sexes, etc.) and/or multispecies (which are part of our immediate neighbourhood), trying to fit in their cultural, sociological, economical and ecological contexts and to take into account possible and plausible outcomes (and sometimes unexpected uses) for a project. It is precisely with such a diversity of needs to be necessarily aware of motion in understanding these very needs. According to professor of transdisciplinary design, Jamer Hunt (2021), movement is a part of scale because when one moves, the problem changes. The point is not to shape the present, but to think through the present, to maintain inequality to no longer design, but ‘undesign’.

As we both come from different professional backgrounds (architecture and design) and have experienced international education, we both saw the project through different lenses. In architecture, I (Mara) got trained to be sensitive to perceive and analyse space and learned early on to engage and experiment with scale either in drawings or models. Since the very beginning of my architecture studies, I have worked for several years in creative studios across Europe and within a wide range of scales, that not only helped me to zoom in and out, but also to see connections between different disciplines and spatial contexts. My appreciation (Marianna) for research through design practice was initiated during my interdisciplinary master’s degree that explored the intersection of design, digital technologies and geopolitics. As I consider being a designer as a possibility to shake the status quo, I am interested in exploring how design can discuss a broad range of contexts: cultural, social and technological and therefore, start a conversation. This is a result of working in international teams and my own exploration of the methodology of speculative design.

Research is often considered as an introductory stage to a design process as a tool to collect information and to find state-of-the-art solutions and references. We both agree that its role moves beyond only that: that it could be also an instrument to ask questions through, i.e. experiential objects and scenography of a design project. Thus, the installation Motion of Scales investigates the role of materiality in architecture as a performance experience through established forms of research. This visual and reflective essay reviews and discusses the possibility that performativity can support practice-led research. Compared to practice-based research, which focuses on an artefact/object to arrive at new knowledge, the installation did not aim to contribute to research at first glance, but to challenge body perception in relation to scale. According to Mäkelä and Nimkulrat, practice-led or artistic research is not really new but the ‘connection between the art practice and the university institution’ (2008: 2) is a new field of experimentation in academia. The crucial element within this intertwined approach is the documentation, that is, reflection on the practice itself. ‘Critical thinking and objectivity in the practitioner’s actions may be called critical subjectivity, the term used in action research’ (Mäkelä and Nimkulrat 2018: 2 ‘original emphasis’). Performative design research takes into account the ‘sensual-corporeal experience’ in order to not ‘research about art, but rather with art’ (Schnell 2021: 23 ‘original emphasis’). The fact of experiencing the installation and discovering embodied knowledge is an essential component of Motion of Scales. It is, indeed, a contribution to the design process. Our intention was to offer a rendered experience that is not a finished product but an ongoing process, heavily dependent on individuals’ approaches and subject to personal interpretations. Deciding to invite the intimate process of decision-making to the site, which was influenced by the images accompanying the open call, was the starting point for our design programming. Working with ‘unknown’ and unexpected human factors was always crucial to the final (but open and gradually unveiling) installation we wanted to propose. Motion of Scales is an attempt at staging an immersive experience by confusing the notion of reality embedded in bodies and senses of passers-by.

According to Schnell, Sommeregger and Indrist, there is a ‘performative turn’ in architecture, which they discovered through their architectural teaching at the Institute of Art and Architecture (IKA) at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (2017). In 2016, the trio published the book entwerfen erforschen (‘Design explore’), which addresses the question of what design-based research is and what it can actually do. The authors emphasize the potential of the ‘performative turn’ in architecture and design-based research. To clarify, the performative turn had its main impact in the social science and humanities in the 1990s. It assumes that the humans’ action is performed and has its root in the speechact theory by Jane Austin from the late 1950s and early 1960s, which proceeds from the fact that while we speak it impacts our following action. While we were developing the installation, the ‘performative turn’ was a crucial base as (assumed) participation that would contribute to the research side of the project. In this regard, following stages we encountered offer different perspectives and ‘reflections on the creative processes conducted’ (Mäkelä and Nimkulrat 2018: 3): initial phase, conceptualization, (remote) production, installation, participation, documentation and aftermath reconfiguration-reflection. One of the key moments of this changed perspective is the video footage from the installed GoPro on top of the curtain. It serves not only as an aesthetic accomplishment or as project documentation, but also as a pedagogical tool and a new source of embodied knowledge from a bird’s eye view. It reveals movement patterns of encounters that had or not happened and offers us a better understanding of material that we used and verifies our intentions (the design programme).

Design Programme

We call it a ‘design collision’: understanding and comparing our personal approaches to subjects and creatively reworking them together. What we found particularly fascinating was how scale was something under-discussed: assumed, seemingly universal and devoid of deeper reflection. How could it be more dynamic and interactive? As much as the open call initiated our discussion and a closer look into what scale ‘was’, it was the Narrow Path that gave an initial direction to questions we would like to raise through our project. The limited site was challenging and accidentally activated by passers-by taking a shortcut who actually claimed the space. We did want to embrace those decisions and to make them a part of our proposal and to keep the installation open, unveiling and an on-going design.

Openness

Decision-making

Transparency

Spontaneity

Human agents

Spatial conditions

Formal requirements

Intriguing

Observation

Experiential

Documentation

Motion

Fig. 2: Installation.

Enactment

An unexpected, enacted stage of our installation happened during a remote production of the piece, with video calls consulting of and on the site with technical experts who would help us to prepare construction pieces to be installed. In a sense, the pre-stage action was a performance itself, with enacting embodied knowledge and passing it via the internet, adding yet another dimension to the project (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Video call with Eva Brandt (Kolding) and Mara Trübenbach (Leipzig) in July 2021.

It was when we both, designers and curators, became active participants as well. Through different agencies such as weather, site, building, etc. the proposal got a setting, a décor that invited the material to activate our proposal (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: View to the top of the installation.

The stage was the building with its colour and dimensions, framing a space to act with and within. Whereas the site (connecting street in the city centre) acted as a prompter, i.e. it helped passers-by to literally get back on the right track when they were irritated by the two curtains. The design proposal and drawings of the installation were the script, a principal instrument that guided the idea of a scale in motion. Since it was planned out remotely, the site and helper and their knowledge of where to get tools to mount the installation or how to install the technical equipment of the GoPro were not only essential but became a main condition for realization.

The main actor though was the fabric, which I (Mara) first saw on the day before the installation. Marianna chose the linen in Poland, which was tailored there and shipped to Kolding afterwards. During my visit at the textile warehouse I (Marianna) had compared different levels of transparency and flexibility of the material, resulting in various thickness and colours and video-called Mara to discuss it (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Set of different linen.

With a few small samples I tried them out ‘in the wild’: shadows, sunlight, wind or no wind (see Figure 6). I experimented with how they acted in contact with water and determined they required additional weight, so lead wires were sewed in at the bottom.

Figure 6: Marianna Czwojdrak (Poznan) testing the material.

When the fabrics were mounted and the camera installed on the top, I (Mara) passed through it for the first time. The front layer was dancing in the wind, captured between orange and red adjacent walls. I could not see what would come next unless I touched the linen and passed the first one. It was an excitement that was followed by insecurity. Standing between two translucent fabrics, which wrapped my body passively in the Narrow Path, I felt uncomfortable and my body felt small. The only exit was the gap above me with no curtain or wall to limit my view and I could look up into that cloudy sky. Suddenly, my senses felt awakened. I noticed music coming from a nearby bar at the end of the passage and some people curiously looking into it. I set myself free by sliding the second curtain to arrive on the other side of the installation and thus stand in the midst of the bar scene of Kolding (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Experiencing the installation.

By deciding to ‘amplify the narrowness’ of the site, we decided not to fix this unfriendly venue (moving away from the design instincts that are commonly taught at design schools), but to play with its original characteristics. Two curtains were installed to close it and to make it even narrower and to limit visibility with overlapping textile pieces. The linen played a critical role in opening a dialogue between: human agents, pre-existing spatial conditions and the formal requirements by creating an unexpected stage right in the city centre. A possibility of exchange of gestures between strangers, textile and changing weather conditions hoped to create an experience that could rework the common understanding of scale we discussed above. The question of how it would be touched and experienced was crucial in choosing the right textile at the right size or for that matter: at the right scale. The task was not just to act as a perceptual confusion or a visual distraction, but to evoke emotional reactions through the interaction with the fabric. According to Giuliana Bruno, ‘[e]motions are produced within the fabric of what we touch and from that which touches us: we “handle” them, even when we cannot handle them. Emotional situations are touchy, indeed’ (Bruno 2014: 19). Our goal was to rework the common understanding of scale only as a measuring tool and to examine its performative potential: how it could become a relative unit of perception and personal emotional interaction. As the lightweight and translucent material, it was exposed to weather conditions such as rain and wind, which together created mimicry of body movements and demanded the attention of passers-by in their uncontrollability. Its translucency became another layer of emotional impact: is there someone on the other side? Do I still want to enter it or am I afraid of a possible encounter? Uncertainty, fear and curiosity were invited into the place. The experiential approach of pushing agents into a limited position of two-choice situation (participation or withdrawal) stems from the research concept of embodied knowledge.

Reflections

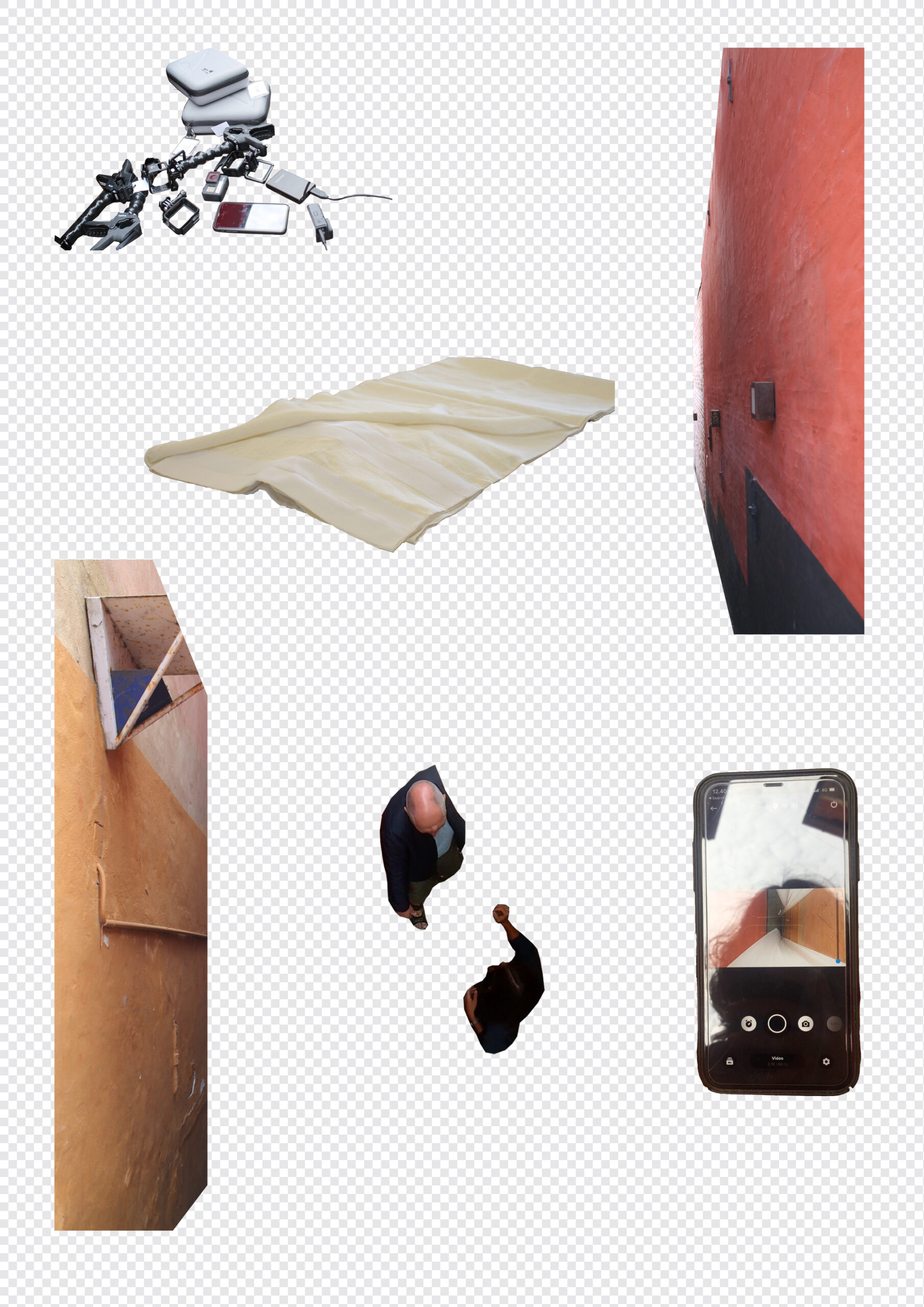

A body is a central point for other agencies (material, weather, building, human and emotions), and it coordinates a series of relationships, interactions and networks of support, all of which respond to each other: actively or passive, implicitly or explicitly. The experience verifies expectations and challenges preconceptions. As early as the late 1940s, the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty (1948) claimed that perception is experienced through the whole human body and is central to making sense of the world. According to architectural theorist Jonathan Hale, phenomenology is not a design method for architects, but a strategy to discuss architecture ‘from the perspective of [architects’] lived experience as embodied building users’ (2017: 5). We want to embrace Hale’s assumption by adding the layer of performance. Performing disturbs the body seeing through the bodily experience, creating unexpected perceptual angles through cinematic documentation with GoPro camera (agent a) mounted on top of the curtains. The top view documented a passer-by (agent b) and interrupted, not only by an encounter with a counterpart (agent c), but also by the fabric (agent d) and weather conditions, for instance, wind (agent e) (see Figure 8).

Fig. 8: Top view of the installation.

In other words, participants interacting with Motion of Scales do not witness social reality but are forced to get conscious about current surroundings and to reflect on their behaviour. Motion of Scales interrupts the expected inputs and two linen fabrics convert the Narrow Path into a scene of gesture exchange. So, what it is, that Motion of Scales lets its participants experience is not the action, but to spot a moment, a condition. In this sense, we argue, there is no single actor, but rather a condition, a sequence of dialogues between materials and humans that serve as agency generated through the performative potential of the object made (Yaneva 2022), such as this installation has shown us.

Such dialogues create new memories and experiences that are important to create a sensitive perception of the immediate environment. Those circumstances were discovered in the interruption of processes and are, in fact, the ‘ongoing act of becoming’ of both subjects (human and non-human) and the interaction in between.

The whole process of the installation unfolds the different steps that were necessary to make the enactment happen. Collecting tools and material,mounting, probing different camera settings and angles in order to think how to capture the event, experiencing and observing – all highly relevant to the reflection based on the conference walk and its discussion afterwards. The documentation poses questions such as: how can performativity intervene in design research to create space for both conflict and cohesion? What new forms of deliberation, communication and understanding can be fostered through the creative process (documentation)? The reflection exemplifies the urgency for including various agents in research and the quality of reflexivity, decision-making, gesture exchange and emotions. In other words, we experimented with the effect of the textile serving as an educational platform. Thus, it was not only individual experience with material that taught us new knowledge but also the observation of other people when going through the installation. The material became an interactive agent, mediator and ‘critical substance’ all at once (Lehmann 2017: 27). This embodied approach reveals the way passers-by think about (mindset i.e. moment of decision-making), act with (spatial perception i.e. movement of the body) and respond to (sensual experiences i.e. evoking emotions and memories) the environment that co-exists with animals and materials. Returning to the notion of ‘critical subjectivity’ coined by Reason (1994: 326–27) and advocated by Mäkelä and Nimkulrat (2018: 2), we explore personal experiences as contributions to performativity of materials from a reflective viewpoint. This live-build project, with all its different layers of documentation, identifies the reciprocal scale of site, body and material (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Collage deconstructing each actor involved.

Motion of Scales required a constant input of interactions, agents (non- and human), decisions and emotions. The installation interrupts expected inputs and two linen layers convert an urban connecting path in a city centre into a scene of gesture exchange. Therefore, we think of it as a prototype that evolves every time a little differently than before depending on the factors aforementioned. It is a flux rather than a finished product that fulfils its purpose through performance. The performative potential of the installation stems not only from the movement of (and literally between) curtains and humans, but also from the key moment of decision-making: becoming active or remaining passive.

Repurposing of Scale

A year after the conference the two linen curtains are still there. Not as an art installation in the city centre of Kolding, but in Mara’s dining room in Leipzig (see Figure 10). To be able to reuse the curtains they were cut 1.5 m that changed their scale immediately. Each time I (Mara) pass through the two curtains to enter the balcony, not only do I remember the size of tall buildings, but also the emotions I felt back then. The textile’s purpose is no longer to arouse curiosity about what is happening behind, but to add warmth and cosiness inside, to keep the sun out and to cool down the room. The linen curtain performs again, in a different environment and in a different context, yet it still evokes emotions.

Figure 10: Fabric’s in Mara’s dining room.

References

- Bruno, Giuliana (2014), Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media, London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hale, Jonathan (2017), Merleau-Ponty For Architects, Thinkers for Architects, Oxon and New York: Routledge.

- Hunt, Jamer (2021), ‘The powers of eleven: How shifts in scale are remaking the possible’, in E. Brandt, T. Markussen, E. Berglunden, G. Julier and P. Linde (eds), Proceedings of Nordes 2021: Matters of Scale, Kolding, Denmark, 15–18 August, p. 33.

- Jensen, Ole B. (2021), ‘Rethinking scale-relationality, place and critical zone’, in E. Brandt, T. Markussen, E. Berglunden, G. Julier and P. Linde (eds), Proceedings of Nordes 2021: Matters of Scale, Kolding, Denmark, 15–18 August, pp. 39–47.

- Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2017), ‘Material literacy’, Bauhaus, 9:20–27, p. 27.

- Mäkelä, Maarit and Nimkulrat, Nithikul (2018), ‘Documentation as a practiceled research tool for reflection on experiential knowledge’, FormAkademisk, 11:2, pp. 1–16.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1948), The World of Perception, Oxford and New York: Routledge, p. 62.

- Reason, P. (1994), ‘Three approaches to participative inquiry’, in N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 324–39.

- Schnell, Angelika, Sommeregger, Eva and Indrist, Waltraud (2016), Entwerfen Erforschen: Der ‘Performative Turn’ Im Architekturstudium, Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Schnell, Angelika (2021), ‘Performative design research: En-acting knowledge in teaching’, in L. Schrijver (ed.), The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research, Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 23–36.

- Yaneva, Albena (2022), ‘Missed magic: Models and the contagious togetherness of making architecture’, E-Flux Architecture, 13 September, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/on-models/489649/missed-magic-modelsand-the-contagious-togetherness-of-making-architecture/. Accessed 15 September 2022.