Return to archive

title

Teaching Design in a Post-Rainbow Nation A South African Reflection on the Limits and Opportunities of Design Praxis

Credit

Orli Setton, Eric Wright, Claudia Morgado, Blanca Calvo, residents and leaders of Denver Informal Settlement and the UJ Professional Practice students from 2013 to 2017.

Abstract

There has been an intense discourse on the relationship between inter-stakeholder university engagements, or service learning, and the broader society that South African universities claim to serve over the past decade in both local and international academia. The inherent problem within these power structures, the challenges to achieving mutually beneficial project outcomes and the growing concern of vulnerable, unheard institutional and individual voices are critical factors. The recognition of these dynamics within the emerging field of design research and design-led teaching is less nuanced in these debates. Training institutions of architecture have a rich history of undertaking service-learning initiatives to create value and learning for both the students and the stakeholders of such projects. Still, in South Africa, they are only now seen through a post-rainbow nation lens. The FeesMustFall movement is primarily driving this change. Larger institutions are recognising previously marginalised voices that now find traction in learning and practice across South Africa. This chapter reflects the author’s experience with emergent views and concerns as a researcher, lecturer and spatial design practitioner in Johannesburg. This section centres on learning regarding city-making in Southern Africa, and it presents two case studies followed by a discussion of growth opportunities.

- Students and staff of AT working with Denver residents on the Action Research Studio (Author’s photos)

- Challenging practice students engaging in the workshop debate (The author’s photos)

- Challenging practice students engaging in the workshop debate (The author’s photos)

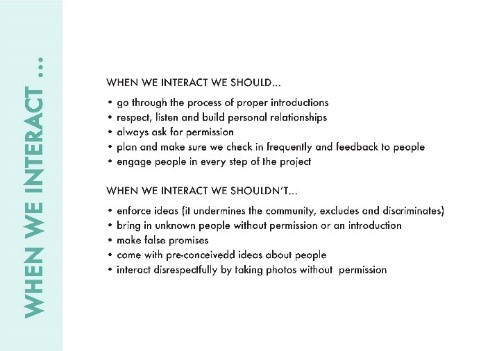

- Example co-developed code of engagement (Author 2017)

- Example co-developed code of engagement (Author 2017)

Introduction

The use of the term spatial design recognises a sector delineation within the broad field of design and ameans to focus on the interdisciplinary practices that work in the realm of human-centred spatial systems––usually with a sociotechnical application for/with people as the core element (Fassi et al. 2018). Typically, this includes the disciplines of Architecture, Planning, Interaction Design, Industrial Design and other aligned sectors that work between their disciplinary boundaries on issues of human-centred spatial systems and are essential in city-making. The southern urbanist contextualisation of spatial design in South Africa is a vital aspect of its framing. Bhan (2019) points out the need for more grounded and contextually appropriate approaches to understanding city-making practice in response to the dominance of northern urban nomenclature. The Lefebvrian description of spatial practice frames the term spatiality. According to Schmidt’s reading of Lefebvre, it is how these shared spatial moments collide, interact and are filtered by the different interpretations of the city at every moment and every day (Goonewardena et al. 2007). These collisions of interaction, or lack thereof, belie an opportunity for what Pieterse (2011) identified as “an opening up of a fertile research agenda for more grounded and spatially attuned phronetic research” (p 12). The author centres this chapter on this identified opening and focuses on engagement with the opportunity for spatial design related to city-making 1 City-making is a term drawn from Isandla’s (2011) Right to the City document, which outlines the principles of city making through a rights-based approach developed with a range of local stakeholders on 11 core principles of inclusive city making. and design-led learning 2 Design-led research refers to strategies, tools and methods of inquiry that are activity based, requiring the subjects undertaking the activity to pursue design solutions to a problem objectively through an iterative process of designing and researching (Laurel 2003). in South Africa.

City-Making and Research Praxis in South Africa

South African cities are experiencing an unprecedented shift in growth and control as the country nears its fourth democratic election (Gotz et al. 2014). The loss of majority political control by the post-1994 ruling party to its opposition in three out of the five significant metropolitan areas, combined with the growing disillusion with the rainbow nation 3 The Rainbow Nation or Rainbowism was a concept employed by the newly elected democratic government in the early 1990s as a tool for inclusive nation building post-Apartheid (Msimang 2015; Godsell and Chikane 2016). articulated by student leaders in the FeesMustFall 4 FeesMustFall was the name given to the student protests between 2015 and 2016 that called for the end of student fees and equal access to the nation’s resources for people of all socio-economic statuses. protests, suggests an uncertain future for a rapidly urbanising country (Godsell and Chikane 2016). Specifically, the ways those who practice and conceptualise teaching and research within city-making spaces engage with each other will become increasingly difficult. That difficulty stems from the growing contestation of the disparate urban identities, making it harder to work meaningfully across polarised city sectors to address emerging urban challenges. Oldfield et al. (2004) stated that “South African researchers have grappled with massive internal socio-economic differentiation and played a wide range of roles in local and national processes of transformation and […] certain global institutions and movements” (p 289). They pointed out the problematic intersectional role that local researchers must navigate in the context of South Africa’s societal inequality structures. These internalised local researchers’ power dynamics and intersectional positionality issues are a recurring topic in southern urbanism (Parnell and Oldfield 2014; Bhan 2019). It signifies the need for contextual nuance. Although the traditional dichotomy between university and the field is a global issue, it contextualises in patterns for southern cities (Simone 2004) that the author believes require a locally developed approach. These terms find more relevance through discussion with students concerning the concepts brought forward by the leaders of the FeesMustFall protest (Msimang 2015; Chikane 2018). The author recognises the depth of dialogue on university engagements with more vulnerable sectors of society outlined by South African researchers such as Brown-Luthango (2013). The author points out that there remains little focus on how the spatial design and related socio-technical design disciplines are taught or practiced to address how cities are produced, managed or perceived meaningfully (Combrinck and Bennett 2017). Institutes such as the University of Witwatersrand’s School of Architecture and Planning, the SouthAfrican CitiesNetwork and the NelsonMandela University’s Missionvale Campus have been largely successful (NUSP 2015) in creating relationships between local and national institutions. Compared to unengaged city-making officials and practitioners who are not willing to engage with aspects of spatial design in post-apartheid South Africa, they remain a minor force. The training, research institutes and professions charged with guiding development agendas, or re-development 5 Re-development is a term employed by the author to recognise the uneven development of South African cities since the geopolitical formation of South Africa in 1652. in the case of South Africa (Oldfield et al. 2004), are the very people who lived through a lifetime of segregation. They received almost no recognition of the trauma they experienced (or perpetuated), or any emotional support (Biko 2013) to deal with the sociocultural scars of South Africa’s historical development. As a result, many educational actors still teach and practice in a manner that ignores or reinforces the very psycho-spatial (Petti et al. 2013) culture that created the city we know today. Edward Said (1978) made this claim forcefully in his seminal text, Orientalism, when he stated that “ideas, cultures, and histories cannot seriously be understood or studied without their force, or more precisely their configurations of power, also being studied” (p 5). This distancing of one’s positionality from the research in design-led learning and design-thinking reflects Said’s sentiment, as some of the tools made famous by the commercial market’s use of design thinking and social innovation, such as rapid ethnography, are often seen to other those involved in the research (Campbell 2017; Setton 2018) which can lead to harmful and damaging practices. Although other disciplines are better versed in these discussions, it is not commonly found in the spatial design and design-led innovation fields in South Africa (Le Roux and Costandius 2013). This disempowerment of local people and the lack of mutual benefit combined with the growing popularity of these courses are contributing to local research fatigue (Winschiers-Theophilus et al. 2010), while the bias prevents authentic relationships across social boundaries (Setton 2018). The notions of engaging the more layered consciousnesses of this work are discussed by Kruger (2017), who describes the work of engaging with South Africa’s legacy of inequality as woke work to design. She states that “The conceptualisation of design as woke work emphasises praxis in a particular mode of consciousness, namely being woke to social inequality and its causes. It also valorises the work that goes into design as a form of social deliberation or mode of critique and exploration rather than as an economic enterprise” (Kruger 2017, p 119). The sentiments expressed by Kruger draw from the vocabulary of student activists in the FeesMust-Fall and RhodesMustFall movements, which illuminate the sociopolitical reality of South Africa as a post-rainbow nation.

While this critical perspective on the use of design-based approaches is not new, the author believes that it is vital for South African teachers and practitioners to address recognition. At the same time, they continue their work of teaching and researching city-making in Johannesburg and other South African cities.

Methodology of the Case Studies and the Chapter

The two case studies support constructive thinking. A narrative summary dissects each case study and critically reflects on the limits and opportunities. The conceptual choice of these headings draws from the work of Schön (1983). The writing on reflection on action provides a means of framing the methodology of this chapter. A set of didactic reflections on each case study offers thoughts to future teachers and researchers as they embark on similar endeavours. Reflective social science practices and design methods of research, according to Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000), call “for an awareness among researchers of a broad range of insights: into interpretive acts, into the political, ideological and ethical issues of the social sciences and into their own construction[s] of the ‘data’ or empirical material about which they have something to say” (p 34). The use of the limits in contrast to the opportunity serves as a proactive summarisation for other practitioners (Schön 1983) working in the Global South. The technique of contrasting the boundaries and limits with the potential opportunities speaks further to Alvesson’s point: “Reflectionmeans interpreting one’s own interpretations, looking at one’s own perspectives from other perspectives and turning a self-critical eye onto one’s own authority as interpreter and author” (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2000, p 34).

It is crucial that as a body of teachers and practitioners, we recognise these limits and develop our own contextually appropriate means of addressing these realities.In support, the framing of the opportunities offers proto suggestions on areas of understanding that could lead to actionable ways to work through the limits.

Reflexive Case Study A: StudioATdenver

A Background to Service Learning and Design-Led

Research at UJ

During the formation of the University of Johannesburg 6 The University of Johannesburg (UJ) is the result of the merging of several different Apartheidera racially and technically segregated universities, The Rand Afrikaans University, Technikon Witwatersrand, and the East Rand and Soweto campuses of the Vista University were brought together in 2005 under the new banner of UJ (University of Johannesburg 2005). (UJ), a new structure for the Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture (FADA) was built. It was a space of collaboration and cross-disciplinary learning (Campbell 2008). Within the faculty, a newly launched master’s in Architecture course was launched in 2011, and it started to experiment and develop new ways of conducting research and teaching. This course pushed the limits of design-led research while critically grounding the students into their local context further. Many design-led studios supported local groups with socio-spatial challenges. They productively blended teaching and socially engaged design support while speaking tactically to systemic governmental development mechanisms. The university fully implemented the resulting design, which included a strong public commitment to service learning 7 The 2016 CE Report defined service learning as “A form of community engagement that entails learning and teaching directed at specific community needs and curriculated into (and therefore also addressing part of) a credit-bearing academic programme. It enables students to participate in, and subsequently reflect on, contextualised, structured and organised service activities that address identified service needs in a community. It seek[s] to infuse students with a sense of civic responsibility by promoting social justice” (UJ CE 2016, p 5). within the Community Engagement (CE) department. The endeavour is a recognised area of support within the project structuring (UJ CE 2016).

In the author’s experience of teaching and working at universities in South Africa, he has seen CE departments struggling to engage critically with the complex issues of the previously mentioned power structures that plague this type of work. Projects approved by CE departments are symptomatic of uncritical engagement with a most vulnerable constituency, despite the efforts to change. The university system at large struggles to provide support or guidance in stakeholder or community relations, or holding staff accountable for any conflicts, bad engagement processes or unethical behaviours. This guidance usually takes place in interpersonal discussions between faculty and staff members at the departmental level. This issue is not isolated to UJ, but is endemic across tertiary education institutes across South Africa (Winkler 2013). University ethics boards are in place to govern these issues in research. Still, they seem more concerned with protecting the university’s legal position (Oldfield 2008) than with protecting the groups engaged with CE projects. This attitude of service learning and accountability reflects Butin’s assessment of service learning: “Service learning programs […] have promoted much goodwill among those doing the actual service-learning, but there is considerably less evidence that it has provided much benefit for the recipients.” (Butin 2010, p 7). The author echoes Butin’s sentiments. There is a missed opportunity in working toward more grounded and reflexive codes of practice allowing space to engage the ethical and moral dilemma of these inter-stakeholder relationships. There remains a distinct lack of ameaningful “post-colonial critique” (Rankin 2010, p 184) to date.

StudioATdenver 2014–2017

The design studio–Aformal Terrain (AT) 8 Eric Wright, Claudia Morgado, Alex Opper and the author began the collaboration of AT in the wake of the informal studio’s closure in 2014. Opper withdrew from the collaboration and declined further involvement in 2015. –emerged from the closure of the Informal Studio 9 See http://www.informalstudio.co.za. in the Denver Informal Settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa, and set out to operate as a collective architecture/urbanism/landscape laboratory that would closely engage with the complex urban conditions in South Africa (AT 2015). AT set its focus on integrating resources and skills towards promoting awareness and generating appropriate responses to a context of rapidly changing and often fluid contemporary urban situations in post-Apartheid Johannesburg. People-driven methodologies underpinned the approach of the collective for engagement, research and design. It was conceived as a vehicle to develop ways of working and supporting cross-stakeholder configurations in design-led projects. Each iteration of the collective’s work was developed differently. The teaching and research project with Denver Informal Settlement leadership was conceptualised as a design-led studio and titled the studioATdenver, which was described as an “ongoing teaching and learning course in collaboration with residents, [the] community leadership and multiple stakeholders” (AT 2015). The studio sessions took place over 6–8 weeks as an integrated design-led learning and action research space that linked undergraduate and postgraduate students from UJ’s Architecture and Planning Department in a focused engagement with both residents and the leadership of the settlement. The curriculum was driven by community-based planning principles cited in the broader works of Nabeel Hamdi (2010) that were intended to build a collection of responsive and co-produced strategies for upgrade and improvement in what AT termed short-, medium- and long-term time frames. These were not fixed periods, but placeholder terms for later dates to be settled by the leaders and other tactical stakeholders.

The type of support was adapted constantly to respond to the changing needs of the local leadership in the face of government interest to develop the settlement 10 Under the National Development 2014 Target of upgrading over 400,000 well-located informal settlement homes (Department of Human Settlements 2018). as well as smaller emergency events that occurred during the studio sessions. This ever-changing support dynamic shaped how AT structured the student briefs support process and made available the limited time and sociotechnical advice for the project.

A key element of structuring the engagement lay in studioATdenver’s 5-year Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which was produced by AT and the Denver Informal Settlement leadership, and through which the team aimed to create an accountable set of guidelines to maintain a sustainable relationship or a “Framework for Dialogue” (Mee et al. 2014, p 807) between the stakeholders and beneficiaries. The instructions proved invaluable in negotiating the ever-changing nature of support and managing expectations of the engagement. The structured MOU and 3 years of close collaboration created one of the major projects: the Positive Numbers Project, 11 The Positive Numbers Project is an ongoing project involving the enumeration of residents within the Denver Informal Settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa. The project incorporates the installation of related way-finding signage in the form of numbered addresses. These signs are linked to a broader short-to-long-term upgrading strategy known as the Community Action Plan, which has been in development over the last 3 years (AT 2017). which linked the social enumeration of the local NGOs and governments with the co-developed community action plan that the earlier studios had produced (AT 2015). The two clearest outputs of the relationship were the Positive Numbers Project and the light public installation of a play space adjacent to the meeting hall–amongst a host of tactical government and cross-stakeholder meetings in which AT supported the Denver leadership.

Limits and Opportunities from the StudioATdenver

We learned about the complexities of managing diverse expectations, stakeholders and requirements due to our involvement in these dynamic projects. Heated discussions among and with students on their engagement, and more importantly, around the residents’ issues and their expectations arose. Butin (2005) declared expectations and connected issues as a necessary dynamic. These issues were addressed in the MOU when the project was established. It seemed that the students and some partners were fighting over the purpose of their participation. All concerns were addressed in open and closed sessions by stakeholder groups, with many discussions uncovering feelings of complicity in creating unmeetable expectations by their mere mention on site. Spaces allowing students and residents to engage with such topics are challenging to build and support, but vital (Oldfield et al. 2004). These spaces were a rich source of learning and they exposed many hidden challenges to the course convenors, NGOs and local government actors.This recognition of the interpersonal challenges reveals pedagogically how critical this space was within the course structure. It allowed the students to share their misgivings and personal concerns on the personal ethics behind such participation. These spaces and their assessments should be built into the course rhythms to prove they are a valuable part of the project, not an aside. The way they produce knowledge should not be seen as a knowledge collection, but as a production of common sense (Bhan 2019) for educators, students and stakeholders of the participative projects. We present a set of planning criteria for future practitioners by recognising limits and opportunities.

Limit—Time Scale and Agency

The nature of this work is always temporary unless one participates in the context or neighbourhood, even with a structured MOU. Participation does not necessarily imply self-help home building by undernourished and overworked people without credit, with inadequate tools and poor materials. […] The central issue is that of control and power to decide. (Turner and Ward 1991, p 134). Turner offers this critical observation of the underlying reasons for participation.

Still, locally, these practices of participation in the built environment and upgrading space require nuanced local critique in the South African context. It is crucial to accept that while working on participative projects will not solve all issues of a group of people (or be able to include everyone), the engagements have definitive endpoints. Project closures and openings designs need to be appropriate.

Limit—Contextualised Positionality

The often-cited critique of international universities landing in global contexts and parachuting in with design projects contrasted our role. After much discussion, the convenors realised that we were actually local foreigners in the context of historically disadvantaged people of South Africa. When landing in such settings, it is important to question one’s bias, for which Isandla (2013) offers three important framing questions on the various forms of participation:

- Who participates?

- How do they communicate and make decisions?

- What is the connection between their conclusions and opinions and their public policy and actions?

Participation in such projects means little if there is no implementation or meaningful feedback to those in power. The intersectional issues of working in such a diverse society (Winkler 2013) as South Africa requires a careful approach to setting up projects of this nature.

Limit—Value Translation

The project allowed for lengthy discussions on the enormous benefits and value of the workshops, and these discussions determined the real beneficiary of this work. Ballard (2008) commented on this disjuncture between perceived value, but not of the necessary deliberations for meaningful engagement. It was challenging to debate and share the questions of who saw the most value in the Denver case among stakeholders. While some benefitted directly and the settlement sits in a different light now with the local and national governments, the timelines to see change are long and hard to translate (Le Roux and Costandius 2013).

Opportunity—Tactical Balance and Tension

An emerging principle from AT lies in the recognition that designing the engagement to support a learning environment while offering valuable socio-technical support is extremely difficult. Still, tactical systems of delivery and support are vital for this work, and they must be built into the pedagogical and impact outcomes. This is an approach adopted by many pedagogical practitioners (Hamdi and Goethert 1997), who built important critical processes into both their teaching and their development practice. Therein lies an opportunity in such projects to frame this tactical balance as a productive tension (Brown-Luthango 2013)–if managed carefully, iteratively and meaningfully.

Reflexive Case Study B: Alternative Practice at UJ

A Background to Spatial Design Praxis for City-Making in Johannesburg

Johannesburg will be one of the ten new megacities by 2030, according to the UN World Cities Report (United Nations Department of Economic Affairs, Population Division 2016). As a result of this nationwide urbanisation and endemic inequality, hundreds of thousands of people must join the informal housing sector each year to gain access to urban opportunities. Informal settlements indicate inequality, the systemic effects of gross spatial variation (South African Cities Network 2016) and the lingering effects of South Africa’s post-1994 psycho-spatial culture, particularly in urban centres, remain fundamentally unchallenged by city makers (Gotz et al. 2014).

It may seem inconsequential how spatial systems (or cities) are researched or discussed. South African post-colonial and post-Apartheid critical writing and discourse proactively challenge the idea of how we accept our given spatial reality (Malaza 2014). The collective psycho-cultural application of making and using city spaces is an often-understated force in city-making (Weizman 2017). The contrasting need to address the “gross inequality and dire need” (Everatt 2014, p 64) and the lack of ability to engage creatively with the issues at hand is not a productive situation. There is an entrenched stigma in the professional discourse around the role of architects and similar spatial design disciplines in addressing the social ills and inequality of post-Apartheid South Africa. The demand for suitably skilled and competent spatial practitioners and approaches to addressing these challenges is becoming increasingly evident (le Roux 2014; Combrinck and Bennett 2017).

Professional Practice—Alternative Practice 2013–2017

The 2011 Department of Architecture master’s programme at UJ offered its students a module in the Professional Practice Course, 12 The original 2011–2012 course, under the original convenor:DrAmira Osman, supported discussion on complex topics of urbanity and inequality in South Africa and fostered an environment of debate and critical thought on what alternative meant in the South African context. Alternative Practice. The author inherited the course as a newly appointed teacher and researcher in 2013 and was flexible in creating a class that discussed what alternative practice means in South Africa. He subsequently began to adapt the original offering to provide a space for a more engaged and productive discussion on what training, the role for architecture and an emerging sector of socially engaged design in South Africa could mean. The course offered a support structure to the design studio and it challenged the built environment professionals’ existing knowledge and perspectives on practice. Exercises included assigning the development of a manifesto for each student, the design of tools for socially engaged practice, as outlined by Petrescu and Trogal (2017) and a discussion and identification of the various practitioners and practices that exist outside the glossy magazines of architecture. The module equips students with knowledge and skills to operate outside the context of conventional design offices and with some understanding of the sociospatial complexity of post-Apartheid South Africa. These discussions have been carefully documented and shared on a digital platform 13 See https://sociotechnicalspatialdesign.wordpress.com/. The course has been tactically linked to 1to1 as both a platform and a link to the real work of the organisation (1to1 2014). that has given each student an accredited author position and that acts as a resource for future students. In 2016, the course linked the UnitedKingdom chapter of Architecture Sans Frontières’(ASF-UK) Challenging Practice 14 “Challenging Practice is a short course methodology that exposes practitioners of the built environment to the complexity of working with communities, government agencies and other spatial stakeholders through an intensive two-day action learning process. Challenging practice is an independent-learning programme that seeks to enable built environment practitioners to engage reflexively with the challenges of inclusive and sustainable urban development. Challenging practice is based on principles of active, dynamic, action-based learning. The programme is grounded in theories of situated knowledge and reflective practice and places a strong emphasis on the ethical component of action-learning” (ASF Int. 2018). (CP) teaching module to the existing course structure. ASF-UK’s CP was adapted to the South African context to expose students to the ASF International (ASF Int) concepts of critical spatial design development. Students also learned about the author’s developing praxis of socio-technical spatial design, 15 Socio-technical spatial design is defined as “an approach to spatial design practice that works with existing social networks through a critical and participative design process to co-produce an integrated, holistic and contextually supportive strategy to any issue(s) faced by an individual or group of people living in a vulnerable condition or spatial context” (1to1 2014). while supporting a space for engaged dialogue on socially engaged design practice in South Africa.

The adapted course began with a carefully structured debate that, after introducing the concepts of socially engaged design practice in South Africa, asked the students to take an opposing position around the question:

Should Architects in South Africa practice socially engaged design–or just do their jobs? Students debated the opposite social position to their chosen one. This Socratic method encouraged individuals to take a stance and build a critical reflection point for themselves later in the course. The debate was intended to be focussed, light and constructive, and it was carefully facilitated. The debate exercise allowed for a considered moment to air these views and opinions and, when aided well, assisted in allowing certain personal or political positions of students and staff to sit better in the learning space. The CP course was typically run by assisting students in working through analysis and discussion tools that guided the two case studies in a group format. A conscious decision was made by the author and his co-teachers first to use a case study from London, a first-world context, to attempt to break the stigma that socially engaged tools and practices are only applicable to developing frameworks. The second case study was a project in Cape Town, a local but not too familiar site for students based in Johannesburg. This curated choice of case studies was an attempt to address the existing stigma of this type of work in South Africa and to engage with and ground these tools for a semi-local context once the students were familiar with the tools and the action-learning group work format. Within the second case study, a short role-playing exercise/debate charade was employed. Students took on the personas of various stakeholders in the Cape Town case study and acted out a process of reaching a consensus on dealing with the challenges of the case study. This embodied debate-charade format yielded rich content over 2 years. Students intimately appreciated the complexity of spatial design development as well as the reality of local and personal politics. The format speaks to methods of embodied practice (Schalk et al. 2017) that are beginning to form a critical pedagogical theory of this type of teaching. This debate also uncovers the limits of socio-technical design in the face of local and national politics and human engagement. It exposes where students feel power lies in South African cities.

In 2017, the course was further adapted to allow for moments of constructive dialogue and action learning, as well as a co-productive workshop 16 The workshop was co-designed with Orli Setton, a trained graphic designer, and it was aimed at developing a critical reflection in design-led teaching for the students, to bring students, community leaders and NGO representatives around the same table and to co-develop a series of principles that future socio-technical practitioners could use. with invited local citizen experts (Blundell Jones et al. 2005), to engage with the idea of an ethical framework that could apply to spatial-design practice. Based on a visual, brainstorming method, mixed groups with representatives from different levels of practice and community engagement produced a list of dos and don’ts for participative spatial planning and design–ideas that perhaps seem integral to specific represented disciplines, but less to others. The visual methods allow for different voices to be carried through the work, and participants often carry difficult topics towards constructive outputs (Rose 2016). The result was a strategy for amode of practice that took more factors into account than merely physical development fabric. 17 The outcome of the workshop was a series of Codes of Engagement that can be accessed by students, the community and technical people to share on a global platform and can form the basis of future workshops and programmes. The codes can be accessed on a globally accessible website (1to1 2018). The workshop provided a design-led space for non-academic and academic participants to engage with the practices they feel are supportive or detrimental to work with groups of people on spatial design issues. The workshop was designed to provide the raw material for 1to1 later to produce a Code of Engagement (1to1 2018) for socially engaged design practice in South Africa.

Limits and Opportunities of the Alternative Practice Course at UJ

The South African architecture profession remains primarily dominated by privileged (mostly white) and upper-income groups of people, who have little relationship to lower-income areas or population groups in South Africa. This sentiment was discussed at length with students in the course. In the face of this, the programme has revealed several significant findings for socio-technical spatial design in South Africa, including first, the importance of communication during the development process–effective communication, which often requires listening and not speaking–a sentiment recognised by local researchers (Brown-Luthango 2013; Winkler 2013). Second, social stigmas and preconceptions are often overlooked issues, and practitioners should be aware of the possibility of their existence, a finding echoed by Oldfield (2008) in regard to the privilege often held by researchers. These stigmas were reiterated by students through the debates and role-playing exercises. And finally, the often-contentious issue of ethics and research, as researchers are often accused of exploiting communities during research based around participatory practices (Winschiers-Theophilus et al. 2010). Regarding the learning experience, the feedback from most students through the post-course assessment has mostly been positive, with students asking for the course to be integrated into their major subjects better or for it to be amore significant part of their year. The negative comments tend to be around the difficulty in navigating the diversity of opinions the student group holds and for more exposure to more specific techniques of making this work applicable within the current professional structures. After several years of teaching, it has become clear that this course represents a noticeable shift in the vocabulary of practice, employed by both the teachers and the students involved in the course. This shift marks an essential change in how knowledge is practiced. For southern urban practice, this is a vital element of the emerging field: Vocabularies of something called urban practice must take this role even more seriously than those addressing, say, the reconsideration of a theoretical or disciplinary canon. (Bhan 2019, p 641).

Limit—The Capacity of Practice

The numbers and scale of impact required to address spatial inequality in South Africa effectively are staggeringly complex and layered. The limits of practitioners in dealing with the issue effectively are clear. This work should not be the silver bullet, but rather a contributing force to shifting a culture of city-making and spatial design practice. This sentiment is echoed in the writings of Irene Molina, who calls for spatial practitioners to recognise their agency beyond their professions (Schalk et al. 2017).

Limit—Student and Practitioner Concerns

The critical reflection on the role of South Africans of privilege post-Apartheid is an emotionally and socially complex task that many students and universities are neither prepared for nor willing to engage with (Osman et al. 2015). The pushback of the students, who were reluctant to participate and the difficulty in discussing the role of architecture in addressing re-development in South Africa was unexpected. The author feels this mainly has to do with students’ intersectional issues on this type of work: ideas such as “White guilt”, “Black tax”, and thinly veiled “Anti-poor” and racist sentiments found their way into the discussions. While these topics have seen much public light since the FeesMustFall protests and they are commonplace in many South African education institutes, they are still tricky to navigate in highly subjective design spaces.

Limit—Professional Institutions

The professional bodies, who play a crucial role in accrediting university courses, especially professional programmes such as architecture, have no real incentive to include this type of work under their umbrella of concerns or regulations. Local teachers and others see the profession of architecture (le Roux 2014; Combrinck 2015) as elitist. This type of work, then, is regarded as charitable, a social obligation, or nice to have, but not a basis for the re-development of South Africa.

Opportunity—Need and Interest in Individuals

This course has led to many discussions amongst students and guests on how this practice could lead to sustainable careers in South African city-making. Government bodies, private practices and entrepreneurs are displaying a growing interest in this type of work, but they do not have accessible examples or categorisations for these practices (Pieterse and van Donk 2014).

What Could This Mean for City-Making, Teaching and Research Spaces in Post-Rainbow Nation South Africa?

Unlearning City-Making in South Africa

South Africa carries ambitions of addressing its large-scale societal issues. Pieterse and Simone (2013) alert us to the danger in the contemporary framing of the discourse on Southern African urbanism, and particularly urban teaching and research practice, primarily dominated by a macro-economic, political and developmentalist lens. This reading of such a fluid, unprecedentedly urbanising (UN Habitat 2017) and dynamic field of research inquiry and applied practice is “dangerous in how it overshadows the necessary nuance and grounded discovery of more phenomenological, interpretative and relational accounts of social and cultural dynamics and psychological dispositions” (Pieterse 2011, p 12). There is often an unanswered question as to whose version of a South African city or experience such a visit should frame or pedagogical approach should support. The framing is made more complicated due to the locally perceived global readings of the South African city and made more challenging to unpack due to the palimpsest of internalised negative perceptions, stigmas of over 400 years of unequal colonial and Apartheid development (Malaza 2014).

The need to temper localised northern perceptions with a grounded understanding is an essential aspect of this work and could be an opportunity to practice approaches of unlearning:

The underlying ethos of these studios should not be one of entering an informal context and superimposing values of formality – but rather demonstrate a willingness to understand and ‘un-learn’ conventional professional practice to respond in ways that respect inherent energies and capacities of informal contexts. This approach ensures a key aspect that would ensure the sustainability of interventions made by a sense of ownership and authorship by the partner and recipient communities. (Osman and Bennett 2013, p 12). The cost of not recognising the need or rationale behind unlearning in our current post-rainbow nation context comes with a continuing devaluing of the disciplines of design (le Roux 2014), in both teaching practice and the built environment. Based on the author’s experience, these tensions manifest most acutely when design-led learning takes place in the field and educators work directly with those affected by the effects of South Africa’s unequal society through service learning.

Limits

Local researchers are afforded proximity of access to vulnerable or marginalised contexts, but they are just as complicit as those who parachute in from abroad and leave with academic resources. The difference is that as local practitioners, we must live and work in the contexts we research, and therefore we can establish a different type of relationship. As researchers and spatial designers, we cannot neglect intersectional power or what positional difference means in the contexts in which we operate (Le Roux and Costandius 2013). While co-design, co-production and other collaborative approaches to designled research (Winkler 2013) offer new and transparent ways to engage with the intersectional complexity described in this paper, they do not appear to be fix-all solutions (Hamdi 2004; Ballard 2008). The way we practice as spatial designers in the field and the classroom and the way we allocate project resources, as well as how we respect people’s time and effort, reflects on our relationships with social and spatial justice.

Opportunities

There is a problematic and uncomfortable opportunity to turn a reflective lens on ourselves instead of those we wish to understand, a sentiment echoed by both Winkler (2013) in regard to the South African city and Butin (2005) on critiquing cities of the north. This process requires internal shifts before (and during) the start to service learning, design-led teaching/research or development projects with vulnerable contexts and stakeholders in our cities–a vital praxis recognised by Brown-Luthango (2013) in her work and supported by the author’s own experience in this sector. These city-making practitioners have few outstanding examples of thriving neighbourhood-making processes to draw from (NUSP 2015; Cirolia et al. 2017). This lack of models is compounded by a lack of skilled practitioners, grassroots or professional, or design activists (Pieterse and van Donk 2014) and builders. The author believes this is a missing sector of practice in South African city-making. The author joins the call from Pieterse and Simone’s (2013) Rogue Urbanism for scholars to investigate and theorise the specific ways in “which various levels, orders and dynamics of spatial organisation and territory are literally fleshed out, animated and rendered new through the unpredictable combination of spatial practices and imaginaries that invariably collide with cities” (Pieterse 2011, p 13) and urges those involved in such work to take on this challenge in their praxis and teaching. We need to acknowledge our limits and complicity in the issues described in this chapter meaningfully and to combine them with rigorous and iterative critical reflection on our societal roles. The latter may be offered to us by the student voices in the FeesMustFall movement. It provides the opportunity to develop new modes of spatial design-led teaching and practice that can support a more systemic approach to re-development in post-rainbow nation South African cities.

Acknowledgements

Orli Setton, Eric Wright, Claudia Morgado, Blanca Calvo, residents and leaders of Denver Informal Settlement and the UJ Professional Practice students from 2013 to 2017.

References

- 1to1 (2014) SouthAfrican socio-technical spatial design resource. In: SouthAfrican socio-technical spatial design resource. https://sociotechnicalspatialdesign.wordpress.com/. Accessed 30 Aug 2018

- 1to1—Agency of Engagement (2018) Critical practice UJ—codes of engagement summary. https://youtu.be/2ueKVEOBiaM. Accessed 16 May 2018

- AlvessonM, SköldbergK(2000) Reflexive methodology: newvistas for qualitative research. SAGE London

- ASF Int. (2018) Challenging practice. In: Challenging practice. https://challengingpractice.org/.Accessed 27 Aug 2018

- AT (2015) StudioATDenver. In: StudioATDenver. http://studioatdenver.blogspot.com. Accessed 16 May 2018

- AT (2017) Positive numbers, Denver settlement, Johannesburg|Africa architecture. In: Votes: 21 positive numbers, Denver settlement a formal terrain research collective-SA. http://africaarchitectureawards.com/entry/positive-numbers-denver-settlement-johannesburg/. Accessed 29 Aug 2018

- Bhan G (2019) Notes on a Southern urban practice. Environ Urban 31(2):639–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818815792

- Ballard R (2008) Between the community hall and the city hall: five research questions on participation. Trans: Crit Perspect South Afr 66:168–188. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.0.0004

- BikoH(2013) The great African society: a plan for a nation gone astray. Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg

- Blundell Jones P, Till J, Petrescu D (eds) (2005) Architecture and participation. Spon Press, New York

- Brown-LuthangoM(2013) Community-university engagement: the Philippi CityLab in Cape Town and the challenge of collaboration across boundaries. High Educ 65:309–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9546-z

- Butin D (2005) Service-learning in higher education: critical issues and directions. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403981042

- Butin DW (2010) Conceptualizing Service-Learning. In: Service-learning in theory and practice. The future of community engagement in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230106154_1. Copyright © Dan W. Butin, 2010, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan Scholarly through PLSclear

- Campbell AD (2008) Industrial design education and South African imperatives. Image & Text: AJ Des 2008(14):82–99

- Campbell AD (2017) Lay designers: grassroots innovation for appropriate change. Des Issues 33:30–47. https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00424Ce UJ (2016) UJ community engagement report 2016. University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg Chikane R (2018) Breaking a rainbow, building a nation: the politics behind #mustfall movements. Pan MacMillan, Johannesburg

- Cirolia L, Smit W, Gorgens T, van Donk M, Drimie S (2017) An introduction. In: Cirolia L, Smit W, Gorgens T, van Donk M, Drimie S (eds) Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: a partnership-based approach. UCT Press, Cape Town, pp 5–21

- Combrinck C (2015) A model to address marginality of the architectural profession in the South African discourse on informal settlement upgrade. Doctoral Thesis, University of Pretoria Combrinck C, Bennett J (2017) Navigating hostile territory? where participation and design converge in the upgrade debate. In: Cirolia L, Smit W, Gorgens T, van Donk M, Drimie S (eds) Upgrading informal settlements in South Africa: a partnership-based approach. UCT Press, Cape

Town, pp 305–322 - Department of Human Settlements (2018) National upgrading support programme. In: National development goals. http://www.upgradingsupport.org. Accessed 27 Aug 2018

- Everatt D (2014) Poverty and inequality in the Gauteng city-region. In: Harrison, P, Götz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds) Changing space, changing city. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, p 63–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.18772/22014107656.7

- Fassi D, Galluzzo L, Rosa AD (2018) Service+spatial design: introducing the fundamentals of a transdisciplinary approach. In: Meroni A, Medina AMO, Villari B (eds) Service design proof of concept proceedings of the ServDes. In 2018 Conference. Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköping, Sweden, pp 848–861

- Godsell G, Chikane R (2016) The roots of the revolution. In: Booysen S (ed) Fees must fall: student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, pp 54–73

- Goonewardena K, Kipfer S, Milgrom R, Schmidt C (eds) (2007) Space difference, everyday life: Henri Lefebvre and radical politics. Routledge, London

- Gotz G, Mubiwa B, Wray C (2014) Spatial change in Johannesburg and the Gauteng city-region. In: Harrison P, Götz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds) Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, pp 269–292

- HamdiN(2010) The placemakers’ guide to building community: planning, design and placemaking

in practice. Earthscan, London - HamdiN(2004) Small change: about the art of practice and the limits of planning in cities.Earthscan, London

- Hamdi N, Goethert R (1997) Action planning for cities: a guide to community practice. JohnWiley, Chichester

- Habitat UN (2017) Global public space programme annual report 2017. UN Habitat, New York

- Isandla (2011) The right to the city in a South African context. Isandla Institution, Cape Town

- Isandla (2013) Planning for informality: exploring the potential of collaborative planning forums. Isandla Institution, Cape Town

- Kruger R (2017) Design work as “woke” work. In: #Decolonise!: In DEFSA 14th national conference proceedings. Design education forum of Southern Africa (DEFSA). Pretoria, South Africa, pp 118–129

- Laurel B (ed) (2003) Design research: Methods and perspectives. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Le Roux H (2014) Design for the missing middle: architecture in a context of inequality. J Archit Educ 68:160–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2014.937228

- Le Roux K, Costandius E (2013) The viability of social design as an agent for positive change in a South African context: mural painting in Enkanini, Western Cape. Image & Text: A J Des 21:106–120

- Malaza N (2014) Black urban, black research: Why understanding space and identity in South Africa still matters. In: Harrison P, Götz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds) Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, pp 553–567

- Mee A, Wright A, Astley P (2014) Rhizomatic healthscapes. In: Proceedings of the UIA 2014 DURBAN architecture OTHERWHERE, W104—open building implementation. CIB Publication 400, Rotterdam, pp 806–815

- Msimang S (2015) Opinion|The end of the rainbow nationmyth. New York Times, 13 April. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/13/opinion/the-end-of-the-rainbow-nation-myth.html. Accessed 2 Jul 2018

- NUSP (National Upgrading Support Programme) (2015) Introduction to informal settlement upgrading. Section 3, The South African housing code: SA upgrading policies, programmes and instruments. http://upgradingsupport.org/uploads/resource_documents/participants-combined/Chapter-3-Policies-and-Programmes-May-2016.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2017

- Oldfield S (2008) Who’s serving whom? partners, process, and products in service-learning projects in South African urban geography. J Geogr High Educ 32:269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701514215

- Oldfield S, Parnell S, Mabin A (2004) Engagement and reconstruction in critical research: negotiating urban practice, policy and theory in South Africa. Soc Cult Geogr 5:285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360410001690268. Reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com)

- Osman A, Bennett J (2013) Critical engagement in informal settlements: lessons from the South African experience. In: Proceedings of the 19th CIB world building congress, Brisbane 2013: construction and Society. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, pp 1–13

- Osman A, Toffa T, Bennett J (2015) Architecture and agency: ethics and accountability in teaching through the application of open building principles. In: Ethics and accountability in design: do they matter? In Conference proceedings. DEFSA, Johannesburg, pp 287–303

- Parnell S, Oldfield S (2014) The Routledge handbook on cities of the global South, 1st edn. Routledge, London

- Petrescu D, Trogal K (eds) (2017) The social (re)production of architecture: politics, values and actions in contemporary practice. Routledge, London

- Petti A, Hilal S, Weizman E (2013) Architecture after revolution. Sternberg Press, Berlin

- Pieterse E (2011) Grasping the unknowable: coming to grips with African urbanisms, Social Dynamics 37:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2011.569994. Reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com)

- Pieterse E, Simone AM (2013) Rogue urbanism: Emergent African cities. Jacana Media, Cape Town

- Pieterse E, van Donk M (2014) Citizenship, design activism and institutionalising informal settlement upgrading. In: From housing to human settlements: Evolving perspectives. South African Cities Network, Johannesburg, pp 149–172

- Rankin KN (2010) Reflexivity and post-colonial critique: toward an ethics of accountability in planning praxis. Plan Theory 9:181–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095209357870

- Rose G (2016) Visual methodologies: an introduction to researching with visual materials, 4th edn. SAGE, London

- Said EW (1978) Orientalism, 1st edn. Pantheon books, New York. Copyright © 1978 by Edward W. Said. Exceprt used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved

- Schalk M, Kristiansson T, Mazé R (eds) (2017) Feminist futures of spatial practice: materialism, activism, dialogues, pedagogies, projections. AADR,Art ArchitectureDesignResearch,Baunach

- Schön DA (1983) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Basic books, New York

- Setton O (2018) From the relational to the technical: a workshop discussion presentation. 17 April 2018 Cape Town

- Simone AM (2004) People as infrastructure: intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Publ Cult 16(3):407–429

- South African Cities Network (2016) State of South African cities report, ’16. South African Cities Network, Johannesburg

- Turner JFC,WardC(1991) Housing by people: towards autonomy in building environments.Boyars, London United nations, department of economic and social affairs, population division (2016) The world’s cities in 2016: Data booklet. United Nations, New York

- University of Johannesburg (2005) Faculty of art, design and architecture: about us. University of Johannesburg. https://www.uj.ac.za:443/faculties/fada/Pages/About-Us.aspx. Accessed 27 Aug 2018

- Weizman E (2017) Forensic architecture: violence at the threshold of detectability. Zone Books, New York

- Winkler T (2013) At the coalface: community–university engagements and planning education. J Plan Educ Res 33:215–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X12474312

- Winschiers-TheophilusH, Chivuno-Kuria S,Kapuire GK, BidwellNJ, Blake E (2010) Being participated—a community approach. In: Proceedings ofPDC2010s.ACM,NewYork, pp 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/1900441.1900443

- City-making is a term drawn from Isandla’s (2011) Right to the City document, which outlines the principles of city making through a rights-based approach developed with a range of local stakeholders on 11 core principles of inclusive city making.

- Design-led research refers to strategies, tools and methods of inquiry that are activity based, requiring the subjects undertaking the activity to pursue design solutions to a problem objectively through an iterative process of designing and researching (Laurel 2003).

- The Rainbow Nation or Rainbowism was a concept employed by the newly elected democratic government in the early 1990s as a tool for inclusive nation building post-Apartheid (Msimang 2015; Godsell and Chikane 2016).

- FeesMustFall was the name given to the student protests between 2015 and 2016 that called for the end of student fees and equal access to the nation’s resources for people of all socio-economic statuses.

- Re-development is a term employed by the author to recognise the uneven development of South African cities since the geopolitical formation of South Africa in 1652.

- The University of Johannesburg (UJ) is the result of the merging of several different Apartheidera racially and technically segregated universities, The Rand Afrikaans University, Technikon Witwatersrand, and the East Rand and Soweto campuses of the Vista University were brought together in 2005 under the new banner of UJ (University of Johannesburg 2005).

- The 2016 CE Report defined service learning as “A form of community engagement that entails learning and teaching directed at specific community needs and curriculated into (and therefore also addressing part of) a credit-bearing academic programme. It enables students to participate in, and subsequently reflect on, contextualised, structured and organised service activities that address identified service needs in a community. It seek[s] to infuse students with a sense of civic responsibility by promoting social justice” (UJ CE 2016, p 5).

- Eric Wright, Claudia Morgado, Alex Opper and the author began the collaboration of AT in the wake of the informal studio’s closure in 2014. Opper withdrew from the collaboration and declined further involvement in 2015.

- See http://www.informalstudio.co.za.

- Under the National Development 2014 Target of upgrading over 400,000 well-located informal settlement homes (Department of Human Settlements 2018).

- The Positive Numbers Project is an ongoing project involving the enumeration of residents within the Denver Informal Settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa. The project incorporates the installation of related way-finding signage in the form of numbered addresses. These signs are linked to a broader short-to-long-term upgrading strategy known as the Community Action Plan, which has been in development over the last 3 years (AT 2017).

- The original 2011–2012 course, under the original convenor:DrAmira Osman, supported discussion on complex topics of urbanity and inequality in South Africa and fostered an environment of debate and critical thought on what alternative meant in the South African context.

- See https://sociotechnicalspatialdesign.wordpress.com/. The course has been tactically linked to 1to1 as both a platform and a link to the real work of the organisation (1to1 2014).

- “Challenging Practice is a short course methodology that exposes practitioners of the built environment to the complexity of working with communities, government agencies and other spatial stakeholders through an intensive two-day action learning process. Challenging practice is an independent-learning programme that seeks to enable built environment practitioners to engage reflexively with the challenges of inclusive and sustainable urban development. Challenging practice is based on principles of active, dynamic, action-based learning. The programme is grounded in theories of situated knowledge and reflective practice and places a strong emphasis on the ethical component of action-learning” (ASF Int. 2018).

- Socio-technical spatial design is defined as “an approach to spatial design practice that works with existing social networks through a critical and participative design process to co-produce an integrated, holistic and contextually supportive strategy to any issue(s) faced by an individual or group of people living in a vulnerable condition or spatial context” (1to1 2014).

- The workshop was co-designed with Orli Setton, a trained graphic designer, and it was aimed at developing a critical reflection in design-led teaching for the students, to bring students, community leaders and NGO representatives around the same table and to co-develop a series of principles that future socio-technical practitioners could use.

- The outcome of the workshop was a series of Codes of Engagement that can be accessed by students, the community and technical people to share on a global platform and can form the basis of future workshops and programmes. The codes can be accessed on a globally accessible website (1to1 2018).