Return to archive

title

UNCOMMONING: ARTISTIC KNOWLEDGE IN ARCHITECTURE

Author

Valerie Hoberg

Abstract

While art and architecture share many characteristics, artistic knowledge offers some specific possibilities for contemporary architectural practice. Based on a theoretical framework around the artistic tacit knowing and with a focus on artistic reflexivity and its potential for knowledge production, the article explores artistic knowledge examples in the work of the Chilean architect Smiljan Radić. They mainly occur in accompanying practices like writing, collecting or photographing, but which are intertwined with and have an effect on the built. A light is shed on the imaginative, critical and transformative potentials of the artistic knowledge. These potentials especially come to play regarding the complexity of contemporary and future challenges for architecture. An outlook uses the example of the Spanish office Ensamble Studio to raise approaches to action and thought for potential future architectural practice. The specific potential of art and artistic knowledge to address complex problems through focused, reflexive, contextual thinking is highlighted as a way to overcome the known and inadequate – here: uncommoning.

The disciplines art and architecture were once part of a unified universal discipline and still share themes, fields of activity or media today. The artistic can appear in architecture as qualitative property of built objects, design practices, modes of representation or conceptions. But how is artistic knowledge characterized as a specific form of knowledge in architecture? How is it formed and what significance can it have, especially with regard to contemporary challenges of architecture?

ARTISTIC TACIT KNOWING

Undoubtly, a specific body of knowledge is formed in artistic practices – however, often it is not necessarily recognized as a value in a ‘classical’ scientific understanding of research. 1 Cf. Dieter Mersch, „Was heißt, im Ästhetischen forschen?“, in Anderes Wissen, Kathrin Busch ed., Schriftenreihe der Merz Akademie (Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2016), 118; and Eva-Maria Jung, „Die Kunst des Wissens und das Wissen der Kunst“, in Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed. (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016), 23. This fails to recognize that art consists of practices that, for example, intentionally deal with alternating movements, integrate vagueness and change perspectives on the known – properties that are important in research in general in order to arrive at new knowledge.

Research into artistic knowledge still continues to be vital, particularly intensified from the end of the 20th century – quite comparable to research into knowledge of architectural practice. In both cases, Michael Polanyi’s description of tacit knowledge can serve as the basis. 2 Cf. Michael Polanyi, Implizites Wissen, 2. Ed. (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2016). ] This practical knowledge is created through actions and against the background of an individual and shared body of knowledge, but is never complete and only becomes conscious through (intermediate) results. 3 Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Reflexive Design? Topologies of a researchh field“ in Reflexive Design. Design and Research in Architecture, id. ed. (Berlin: Jovis 2014), 28. Artistic knowledge manifests itself in the sensory-motor reactions to the aesthetically perceptible work, which can be experienced both by the producing and hereby perceiving artists and (partially) by the recipients. 4 Cf. Jung, „Die Kunst des Wissens und das Wissen der Kunst“, 30; and David Carr cit. at ibid., 29. Additionally, the philosopher Dieter Mersch emphasizes an essential specification of artistic knowledge: the esprit. This includes a humorous exposure or exaggeration, but also a subversion, reversal or critical thwarting of actual determinations. 5 Cf. Mersch, „Was heißt, im Ästhetischen forschen?“, 118–19. This artistic tacit knowing interacts with other forms of knowledge, questioning, updating and supplementing them, but not replacing them. It’s a continuous differentiation.

Furthermore, in art the unconscious and habitual as well as the unknown are not rationalized and minimized, but on the contrary exhibited. 6 Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst“, in Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. (Berlin: jovis, 2006), 9; Elke Bippus, „Poetologie des Wissens“, in Kunst und Wissenschaft, Dieter Mersch and Michaela Ott eds. (Paderborn: Fink, 2007), 148; and Elke Bippus, „Einleitung“, in Kunst des Forschens: Praxis eines ästhetischen Denkens, id. ed., 2. ed. (Zurich et al.: Diaphanes, 2009), 16; and Kathrin Busch, „Ästhetische Amalgamierung. Zu Kunstformen der Theorie“, in Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed. (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2016), 168. It can thereby provide a way to address common knowledge in order to find gaps within or new perspectives on it. 7 Cf. Margitta Buchert, “Anderswohnen”, in Performativ? Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. (Berlin: Jovis, 2007), 48. The following examples unfold this idea of ‘un-commoning’ as a core feature of artistic tacit knowledge also effective in other disciplines.

ARTISTIC REFLEXIVITY

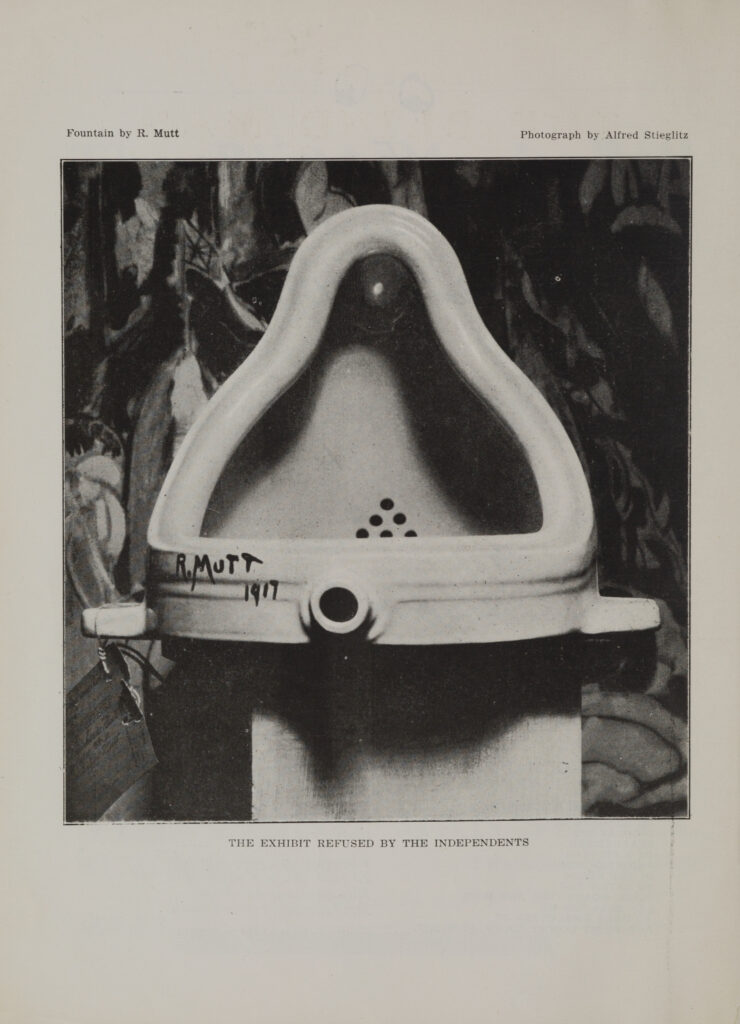

Fig. 1_Marcel Duchamp_Fontaine 1917

Title: Marcel Duchamp (R. Mutt), Fontaine, 1917

Credit: Alfred Stieglitz, artist: Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, Creator: H. P. Roché, Public Domain CC0 1.0

The production of artistic knowledge is rendered possible mainly via reflexivity. Reflexivity has been discussed in various contexts since the 1960s as a stance that includes an individual and collective (critical) questioning of dispositions, ways of acting and projective thinking of possibilities. 8 Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Reflexive, Reflexivity, and the Concept of Reflexive Design“, Dimensions 1, Nr. 1 (1. Mai 2021): 67–76, https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2021-0109; and Buchert, „Reflexives Entwerfen? Topologien eines Forschungsfeldes“. In addition to self-reflection – in art e.g. on one’s own abilities and the work – it is also significant as relational thinking. 9 Cf. Pierre Bourdieu, „Thinking relationally“, in An invitaion to reflexive sociology, Pierre Bourdieu and Loïc J. D. Wacquant eds. (Chicago et al.: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), 224–35. An individual oeuvre only gains meaning through relationships to other oeuvres and to corresponding non-disciplinary discourses. A prominent example can be found in Marcel Duchamp’s (R. Mutt) readymade Fontaine (1917): (Fig. 1) The mass-produced urinal from the sanitary trade becomes a work of art only through contextualization, signature, naming, and exhibiting, as well as publication. It questions the art system and artistic practices, but does not lead to their deconstruction, rather to a (more critical) expansion of possibilities. 10 Cf. Brigitte Hilmer, „Kunst als reflexive Form und reflektierende Bewegung“, Reflexivität in den Künsten, Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, 55, Nr. 2 (2010): 243.

Following these theoretical assumptions: What significance can properties of artistic knowledge have for architecture? Here, the Chilean architecture office of Smiljan Radić is explored as an example. The office not only names numerous artists as references, especially from the 1950s to 1970s, but also pursues artistic work forms and practices in addition to its building designs and structures: texts, drawings, artistic models, exhibitions or collections. 11 Cf. the diverse material in Smiljan Radić, Obra Gruesa/Rough Work, Illustrated Architecture by Smiljan Radic (Santiago de Chile: Puro/Hatje Cantz, 2019); and the publication concerning Radić’s collection of Radical Architecture Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen eds., Cloud ’68. Paper Voice: Smiljan Radić’s Collection of Radical Architecture (Zurich: gta, 2020). Consequently, it is a fruitful example for exemplary artistic knowledge forms in architecture – which of course do not claim completeness.

POETIC KNOWLEDGE: ACTIVATE IMAGINATION

With poeticity is usually assigned a quality that evokes additional worth – often emotions or imaginations – beyond the direct reality. 12 Cf. Roman Jakobson, „What is poetry?“, in Language in literature, id. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 378 This quality is already potent solely by the experience of Radić’s buildings, but gains effectiveness with regard to his practices, especially in regard to language. He is writing texts, assigned to the linguistic genre ‘ekphrasis’, triggering feelings and associations. 13 Cf. Manijeh Verghese, „Weaving spaces with words. Mit Wörtern Räume weben“, in Archiscripts, Daniel Gethmann ed., Graz Architecture Magazine 11 (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2015), 68–83. Also work titles are chosen evocatively, as references – La casa del poema del ángulo recto – or irritating architectural description – Frágil. And foreign texts are used as design sources: Radić’s Serpentine Pavilion (2014), a donut-shaped object with an estranged appearance of being broken up, is the result of a multi-layered design process. First, in 2010, the model El castillo del gigante egoísta was built, which translated emotions and feelings of a tale by Oscar Wilde into an architectural expression. Only in 2014, the model is re-used as a reference for the pavilion, offering formal, material, structural, and atmospheric ideas. The retransference produces estranged aesthetic qualities which are able to trigger the imagination. 14 Cf. on this example Valerie Hoberg, „Entfremdende Interpretationen. Estranging interpretations“, in Intentionen reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Intentions of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed. (Berlin: jovis, 2021), 122–37. Additionally, its title Folly – referring to the historical typology of garden pavilions, which surprise amidst the harmonious, almost perfect garden art and shall distance from the present – explains the architectural effectiveness of the object. 15 Cf. Smiljan Radić, „A Letter from Smiljan Radić – 29 April 2014“, in Smiljan Radić: Serpentine Pavilion 2014, Jochen Volz and Emma Enderby eds. (Serpentine Pavilion 2014, Cologne: König, 2014), 98. (Fig. 2) Here, the currently physically perceptible is expanded and fused – uncommoned from its direct appearance – with imaginative components which might be found in usual aesthetic qualities and are intensified through an additional narrative layer consisting of text or also images. Anecdotal situations are implied, dissonances established or explanations offered that are not purely descriptive. Poetic knowledge consists in the possibility to activate this quality and to make use of it in the design process.

Fig. 2_Smiljan Radić_Folly London 2014

Title: Marcel Duchamp (R. Mutt), Fontaine, 1917

Image Credit: © Images George Rex, „Serpentine Pavilion 2014 / I”, colours changed by the author, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode, (https://www.flickr.com/photos/rogersg/14325677738/in/photolist-nPUQTL-8Nt32E-nQ4Nkn-oo16Pr-AaRKVU-o7ggJK-nQ5pnL-o7ros7-o7gfGV-o7g83X-nQ532m-o7yvVR-o7rnAN-nQ5k5C-nQsYXj-o7sNWJ-nQ5k6F-o9kEgv-d9KJ3k-2dvDbQm-nQ5bE1-nQ54j1-o7sLuE-d9KHyK-d9KHvA-nQ4RmU-d9KG5B-d9KGJC-8B6Ftp-d9KF3P-d9KER7-qnV5d7-2cuaupw-2cuauhh-2cuauwL-2aPygS9-2ccrV1M-2dvDfHm-2dvDfqN-zUshZy-2aPyh53-2dvDeKu-2aPygoy-2ccrUDV-2cuatXQ-2aPyg8o-2cuau6W-2ccrUuX-2ccrUR8-2aPyfRb)

RECEPTIVITY: EXPERIENCING CONVERGENCES AND DIVERGENCES

Fig. 3_ Smiljan Radić_NAVE Santiago de Chile 2014

Title: Smiljan Radić, NAVE, Santiago de Chile 2014

Image Credit: architecture: Smiljan Radić, photo: Valerie Hoberg

Receptivity relies on the idea of an embodied knowledge, especially expressed by the philosopher Maurice Merlau-Ponty. 16 Cf. eg. Polanyi, Implizites Wissen, esp. 20–24; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, „Das Auge und der Geist“, in Das Auge und der Geist. Philosophische Essays, Christian Bermes ed. (Hamburg: Meiner 2003), 298–300. Here, the human bodily experience which uses (re-)cognition of what is known is the foundation for our understanding and interpretation of the world. But in artistic practices, it is not about confirming assumptions and more about overriding them, e.g. by striving for ‘happy mistakes’ as productive moments of serendipity or by producing paradoxes or dissonances for exposing the deviation as ‘something else’. In Radić’s work, this is used and activated by architectural déjà vus: Elements are recognised and understood as something familiar while at the same time irritate perception and estrange people. On a more basic level, architectural situations contrast current experiences with previous and familiar experiences and thus are rendered conscious. This is executed in the dance culture centre NAVE in Santiago de Chile (2014), where a circus tent on the roof amidst the dense urban landscape causes a déjà vu – we are used to sporadically occurring circuses but not in such a dense place on a roof – but also the entire building offers a spatial sequence of oscillating moments. (Fig. 3) A large, seemingly agravic darkness in the main hall contrasts the historic perforated facade, which contrasts the bright but chamber-like rooms of the preserved building, which contrast intensely coloured passageways. In this artistic knowledge form physical experiences are combined with assumptive thinking: divergences are consciously experienced as spatial features, which can provide identity, sense and strengthen structures in complex situations. 17 Cf. Dieter Mersch, „Kunst und Epistēmē“, what’s next?, 12. September 2013, s. pag., http://whtsnxt.net/102. The specific artistic capacity, to add meaning to the aesthetic dimension, comes into play in this case: 18 Cf. Buchert „Reflexive Design? Topologies of a researchh field“, 43. By uncommoning anticipations, meaningful experiences are created, which are open to individual interpretation and adaption.

CONTEXT SOVEREIGNTY: ALTERNATIVE ORDERS

While receptivity tries to produce paradoxes, achieved through a deviation of common assumptions, an alternative framing can also intentionally focus on something other than what is supposedly familiar or obvious – and thereby produce a difference. 19 Cf. Rudolf A. Makkreel, „Einbildungskraft als Orientierungssuche und Sinnkonfiguration“, in Imagination: Suchen und Finden, Gottfried Boehm et al. eds. (Paderborn: Fink, 2014), 139–42. In Radić’s work, this is embodied in practices of collecting, curating, and exhibiting: artifacts, materials, and obsolete objects, as well as photographs of seemingly random, temporarily constructions are collected. These stalls, tents, roadside shrines or rural structures are named Fragile Constructions. Using the same terminology, found objects are assembled to models. In exhibitions, they all stand alongside building models, paintings and drawings, and external artistic references. Through the connecting concept Fragile Constructions, they can all be read as potential architectures – not necessarily meaning ‘buildings’: situational or material properties, spatial experiences, construction methods, local references or potential uses can be found that only emerge through this grouping. But the critical framing of habits and conventions – un-commoning them – also offers the potential to (trans-)form conditions; here, the poor, offhand constructions are introduced into an architectural discourse whereby also the wealth gap in Chile is critically addressed. Sovereignty emerges that empowers architects not only to re-act to constellations, but to act themselves. Also, the disciplinary understanding of ‘architecture’ – Radić, for example, prefers the term ‘construction’ as expression of a multidisciplinary, more open field – is expanded, away from the dominant focus on ‘the object’.

This critical, transformative potential is fundamental for artistic knowledge. It is effective by a self-reflexive attitude with a distance to existing capacities, what one is capable of, has experienced or made, in order to reach out to others, in favour of the unknown – again: un-commoning. 20 Concerning Foucault’s thinking of the exterior cf. Busch, „Ästhetische Amalgamierung. Zu Kunstformen der Theorie“, 170–72; in relation to distancing cf. Valerie Hoberg, „Produktive Distanzen. Productive Distances“, in Produkte Reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Products of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed. (Berlin: jovis, 2022), 84–99. Artistic knowledge includes a ‘knowing how’ to react to so far unrulable complex challenges, whereat outcomes cannot be (completely) determined. This gives it a forward-looking meaning, especially regarding contemporary challenges.

QUESTION REQUIREMENTS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF CREATIVE PRODUCTION

Fig. 4_ Smiljan Radić_NAVE Santiago de Chile 2014

Title: Smiljan Radić, NAVE, Santiago de Chile 2014

Image Credit: architecture: Smiljan Radić, photo: Valerie Hoberg

The complex, networked contemporary world with its multiple crises requires interdisciplinary thinking, which is already inherent to art.

21

Cf. Sabine B. Vogel und Gerfried Stocker, „Teamarbeit: das Leonardo Prinzip für unsere Zeit. Gerfried Stocker im Gespräch mit Sabine B. Vogel“, KUNSTFORUM International 277, Nr. Oktober (2021): 170–71.

It is not (only) the scientific knowledge that enables action – perhaps even on the contrary: e.g. necessary scientific knowledge about the climate crisis has been available since at least the 1970s. Nevertheless, the threatening reality often has a paralyzing effect or is even denied as a result of cognitive dissonance.

22

Cf. Birgit Schneider, Der Anfang einer neuen Welt: wie wir uns den Klimawandel erzählen, ohne zu verstummen, (Berlin: Matthes & Seitz Berlin, 2023), 72–94.

Also the US environmental lawyer Gus Speth stated in 2015: “The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.“

23

Cf. Gus Speth and Steve Curwood, Gus Speth calls for a “New” Environtalism, (Interview), 13. February 2015, s. pag., https://loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=15-P13-00007&segmentID=6.

Artistic knowledge can start right there; it is able to make the threat physically sensible. The work Ice watch by artist Ólafur Elíasson and geologist Minik Rosing on the occasion of COP21 in Paris in 2015 consists of twelve chunks of Greenlandic ice that slowly melt over the course of nine days.

24

Cf. https://icewatchparis.com/, 24.03.2023.

(Fig. 4) Their foreign bodies in the urban show its dissonance with nature and e.g. reflect the too high temperature, but also question diverse phenomena of globalisation. Long-term processes with gradual changes and abstract facts become conscious. Based on and together with scientific knowledge, artistic knowledge expands understanding and, ideally, encourages further action.

But the potential of the artistic goes beyond this activating awareness: While scientific knowledge about the most diverse processes in the world is constantly growing, in turn they are becoming more chaotic and less predictable.

25

Cf. eg. Hartmut Rosa, Unverfügbarkeit, 8. ed. (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2023) esp. 128–131.

In this context, UNESCO, among others, proposes ‘Futures Literacy’ as its capacity to imagine diverse futures and to integrate them into current actions.

26

Cf. https://en.unesco.org/futuresliteracy/about, 24.07.2023.

The artistic tacit knowledge can be important in the creation of alternatives and in addressing the lack of knowledge, the gaps in what is already known, in order to address the uncertainties of the future ahead – also in architecture. It is important to ask what tasks architecture (discipline) has in this context, what will determine it and what opportunities it will have.

GOOD IMAGINATIONS

Fig. 5_Olafur Eliásson_Ice wach Paris 2015

Title: Ólafur Elíasson, Ice watch, Paris 2015

Image Credit: UNclimatechange, „Glacier ice installation ‘Ice Watch’ at Place du Panthéon, Paris (22885211084).jpg“, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode, (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glacier_ice_installation_%27Ice_Watch%27_at_Place_du_Panth%C3%A9on,_Paris_%2822885211084%29.jpg)

Examples of what such sovereign future action can consist of can be shown using the work of the Spanish office Ensamble Studio. 27 Cf. Philip Ursprung, „Earthwards“, 2G, Ensamble Studio, 82, Moisés Puente ed. (Cologne: König, 2021), 4–11. It feeds on two central strands of work – the direct, material-related on-site work and the combinatorics of prefabrication. Work parallels to art can be found in land art and performance art as well as in the space and material-based sculptures of the Basque Eduardo Chillida. Artistic experimentation is an essential practice in both strands of work, and other methods also show artistic ways of acting and thinking. 28 Cf. Valerie Hoberg, „Produktive Distanzen. Productive Distances“. A few examples: They make experimental material studies and design mock-ups in ‘taille directe’ (Megalith wall SGAE, 2007) (Fig. 5), they interpret an obsolete industrial cave into a sculptural space continuum for living and working (Ca’n terra , 2019), they combine manual work and prefabrication to develop new materials and they swap familiar work processes (construction before measuring and plan at Trufa, 2005). Based on their work, which consists of buildings and (still) unrealized visions to a similar extent, it becomes clear in what form dealing with the unknown can produce ‘good imaginations’ for the future. They combine traditional methods with technology from other disciplines for new materials or construction methods. Uncertainty about the outcome of experiments and their design properties is allowed. Questions of resource efficiency are coupled with the human need for stimulating spatial experiences which generates unusual design qualities. And by following the model of architects as ‘master builders’, under which they mostly finance and build what they design themselves, they create sovereignty in order to shape working conditions and the future role of architects and the discipline. An integrative thinking of the complexity of various interdisciplinary challenges is shown, which relies on an architectural common ground, embodied in the two work paths, and in whose repeated differentiation new knowledge and new capacities are gained. The contemporary artistic surplus, addressing cultural self-understandings and questioning them critically in order to try out alternative frames and experimental situations as transformations, comes to play – while operating with and strengthening designerly and knowledge-related core capacities of the discipline. 29 On contemporary self understandings Buchert, “Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst“, 9.

In these contexts, artistic knowledge shows itself as the ability to recognize and think about future challenges and fields of action in the first place. It enables to approach what is not yet known and thus to address what has not yet been mastered. For architecture, the artistic is linked to perceiving or imagining current or future paradoxical situations, starting from a specific perception of the existing, in order to carry out its transformation as a continuous and repeated differentiation. The complex problems of the present and future can only be addressed through reflexive, contextual thinking – which art is a specialist in. Awareness of the common leads to desired un-commoning.

REFERENCES

Bippus, Elke. „Einleitung“. In Kunst des Forschens: Praxis eines ästhetischen Denkens, Elke Bippus ed., 2. ed., Zurich et al.: Diaphanes, 2009, 7–23.

Bippus, Elke. „Poetologie des Wissens“. In Kunst und Wissenschaft, Dieter Mersch and Michaela Ott eds., Paderborn: Fink, 2007, 129–149.

Buchert, Margitta. „Archive. Zur Genese architektonischen Entwerfens“. In hochweit 12, Fakultät für Architektur und Landschaft ed., Leibniz Universität Hannover, Hannover: Internationalismus, 2012, 9–15.

Buchert, Margitta. „Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst“. In Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. Berlin: Jovis, 2006, 9–12.

Buchert, Margitta. “Anderswohnen”. In Performativ? Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. Berlin: Jovis, 2007, 40–49.

Buchert, Margitta. „Reflexives Entwerfen? Topologien eines Forschungsfeldes“. In Reflexives Entwerfen. Entwerfen und Forschen in der Architektur, id. ed., Berlin: Jovis, 2014, 24–49.

Buchert, Margitta. „Reflexive, Reflexivity, and the Concept of Reflexive Design“. Dimensions 1, Nr. 1 (1. Mai 2021): 67–76. https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2021-0109.

Busch, Kathrin. „Ästhetische Amalgamierung. Zu Kunstformen der Theorie“. In Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed., Bielefeld: Transcript, 2016, 163–178.

Fischli, Fredi and Olsen, Niels, eds. Cloud ’68. Paper Voice: Smiljan Radić’s Collection of Radical Architecture. Zürich: gta, 2020.

Hilmer, Brigitte. „Kunst als reflexive Form und reflektierende Bewegung“. Reflexivität in den Künsten, Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, 55, Nr. 2 (2010): 235–246.

Hoberg, Valerie. „Entfremdende Interpretationen. Estranging interpretations“. In Intentionen reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Intentions of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed., Berlin: Jovis, 2021, 122–137.

Hoberg, Valerie. „Produktive Distanzen. Productive Distances“. In Produkte Reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Products of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed., Berlin: Jovis, 2022, 84–99.

Jakobson, Roman. „What is poetry?“, in Language in literature, id., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990, 368–378.

Jung, Eva-Maria. „Die Kunst des Wissens und das Wissen der Kunst“. In Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed., Bielefeld: transcript, 2016, 23–43.

Makkreel, Rudolf A. „Einbildungskraft als Orientierungssuche und Sinnkonfiguration“. In Imagination: Suchen und Finden, Gottfried Boehm, Emmanuel Alloa, Orlando Budelacci, Gerald Wildgruber eds., Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2014, 126–142.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. „Das Auge und der Geist“, in Das Auge und der Geist. Philosophische Essays, Christian Bermes ed., Hamburg: Meiner 2003, 275–317.

Mersch, Dieter. „Kunst und Epistēmē“. what’s next?, 12. September 2013. http://whtsnxt.net/102.

Mersch, Dieter. „Was heißt, im Ästhetischen forschen?“ In Anderes Wissen, Kathrin Busch ed., 102–120. Schriftenreihe der Merz Akademie. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2016.

Pierre Bourdieu. „Thinking relationally“. In An invitaion to reflexive sociology, Pierre Bourdieu and Loïc J. D. Wacquant eds., Chicago et al.: The University of Chicago Press, 1992, 224–235.

Polanyi, Michael. Implizites Wissen. 2. ed. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2016.

Radić, Smiljan. „A Letter from Smiljan Radić – 29 April 2014“. In Smiljan Radić: Serpentine Pavilion 2014, Jochen Volz and Emma Enderby eds., Cologne: König, 2014, 97–99.

Radić, Smiljan. Obra Gruesa/Rough Work, Illustrated Architecture by Smiljan Radic. Santiago de Chile: Puro/Hatje Cantz, 2019.

Schneider, Birgit. Der Anfang einer neuen Welt: wie wir uns den Klimawandel erzählen, ohne zu verstummen. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz Berlin, 2023.

Schrijver, Lara. „From Revolution to Evolution: Resituating ‚Cloud ’68‘“. In Cloud ’68. Paper Voice: Smiljan Radić’s Collection of Radical Architecture, Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen eds., 20–25. Zurich: gta, 2020.

Slager, Henk. „Art and method“. In Artists with PhDs. On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art, James Elkins ed., Washington, D.C.: New Academia Publishing, 2009, 49–56.

Ursprung, Philip, „Earthwards“, 2G, Ensamble Studio, 82, Moisés Puente ed., Cologne: König, 2021, 4–11.

Verghese, Manijeh. „Weaving spaces with words. Mit Wörtern Räume weben“. In Archiscripts, Daniel Gethmann ed., Graz Architecture Magazine 11. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2015, 68–83.

Vogel, Sabine B. and Gerfried Stocker. „Teamarbeit: das Leonardo Prinzip für unsere Zeit. Gerfried Stocker im Gespräch mit Sabine B. Vogel“. KUNSTFORUM International 277, Nr. October (2021): 164–171

- Cf. Dieter Mersch, „Was heißt, im Ästhetischen forschen?“, in Anderes Wissen, Kathrin Busch ed., Schriftenreihe der Merz Akademie (Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 2016), 118; and Eva-Maria Jung, „Die Kunst des Wissens und das Wissen der Kunst“, in Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed. (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016), 23.

- Cf. Michael Polanyi, Implizites Wissen, 2. Ed. (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 2016).

- Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Reflexive Design? Topologies of a researchh field“ in Reflexive Design. Design and Research in Architecture, id. ed. (Berlin: Jovis 2014), 28.

- Cf. Jung, „Die Kunst des Wissens und das Wissen der Kunst“, 30; and David Carr cit. at ibid., 29.

- Cf. Mersch, „Was heißt, im Ästhetischen forschen?“, 118–19.

- Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst“, in Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. (Berlin: jovis, 2006), 9; Elke Bippus, „Poetologie des Wissens“, in Kunst und Wissenschaft, Dieter Mersch and Michaela Ott eds. (Paderborn: Fink, 2007), 148; and Elke Bippus, „Einleitung“, in Kunst des Forschens: Praxis eines ästhetischen Denkens, id. ed., 2. ed. (Zurich et al.: Diaphanes, 2009), 16; and Kathrin Busch, „Ästhetische Amalgamierung. Zu Kunstformen der Theorie“, in Wie verändert sich Kunst, wenn man sie als Forschung versteht?, Judith Siegmund ed. (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2016), 168.

- Cf. Margitta Buchert, “Anderswohnen”, in Performativ? Architektur und Kunst, id. and Carl Zillich eds. (Berlin: Jovis, 2007), 48.

- Cf. Margitta Buchert, „Reflexive, Reflexivity, and the Concept of Reflexive Design“, Dimensions 1, Nr. 1 (1. Mai 2021): 67–76, https://doi.org/10.14361/dak-2021-0109; and Buchert, „Reflexives Entwerfen? Topologien eines Forschungsfeldes“.

- Cf. Pierre Bourdieu, „Thinking relationally“, in An invitaion to reflexive sociology, Pierre Bourdieu and Loïc J. D. Wacquant eds. (Chicago et al.: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), 224–35.

- Cf. Brigitte Hilmer, „Kunst als reflexive Form und reflektierende Bewegung“, Reflexivität in den Künsten, Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, 55, Nr. 2 (2010): 243.

- Cf. the diverse material in Smiljan Radić, Obra Gruesa/Rough Work, Illustrated Architecture by Smiljan Radic (Santiago de Chile: Puro/Hatje Cantz, 2019); and the publication concerning Radić’s collection of Radical Architecture Fredi Fischli and Niels Olsen eds., Cloud ’68. Paper Voice: Smiljan Radić’s Collection of Radical Architecture (Zurich: gta, 2020).

- Cf. Roman Jakobson, „What is poetry?“, in Language in literature, id. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 378

- Cf. Manijeh Verghese, „Weaving spaces with words. Mit Wörtern Räume weben“, in Archiscripts, Daniel Gethmann ed., Graz Architecture Magazine 11 (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2015), 68–83.

- Cf. on this example Valerie Hoberg, „Entfremdende Interpretationen. Estranging interpretations“, in Intentionen reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Intentions of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed. (Berlin: jovis, 2021), 122–37.

- Cf. Smiljan Radić, „A Letter from Smiljan Radić – 29 April 2014“, in Smiljan Radić: Serpentine Pavilion 2014, Jochen Volz and Emma Enderby eds. (Serpentine Pavilion 2014, Cologne: König, 2014), 98.

- Cf. eg. Polanyi, Implizites Wissen, esp. 20–24; Maurice Merleau-Ponty, „Das Auge und der Geist“, in Das Auge und der Geist. Philosophische Essays, Christian Bermes ed. (Hamburg: Meiner 2003), 298–300.

- Cf. Dieter Mersch, „Kunst und Epistēmē“, what’s next?, 12. September 2013, s. pag., http://whtsnxt.net/102.

- Cf. Buchert „Reflexive Design? Topologies of a researchh field“, 43.

- Cf. Rudolf A. Makkreel, „Einbildungskraft als Orientierungssuche und Sinnkonfiguration“, in Imagination: Suchen und Finden, Gottfried Boehm et al. eds. (Paderborn: Fink, 2014), 139–42.

- Concerning Foucault’s thinking of the exterior cf. Busch, „Ästhetische Amalgamierung. Zu Kunstformen der Theorie“, 170–72; in relation to distancing cf. Valerie Hoberg, „Produktive Distanzen. Productive Distances“, in Produkte Reflexiven Entwerfens. Entwerfen und Forschen in Architektur und Landschaft. Products of Reflexive Design. Design and research in architecture and landscape, Margitta Buchert ed. (Berlin: jovis, 2022), 84–99.

- Cf. Sabine B. Vogel und Gerfried Stocker, „Teamarbeit: das Leonardo Prinzip für unsere Zeit. Gerfried Stocker im Gespräch mit Sabine B. Vogel“, KUNSTFORUM International 277, Nr. Oktober (2021): 170–71.

- Cf. Birgit Schneider, Der Anfang einer neuen Welt: wie wir uns den Klimawandel erzählen, ohne zu verstummen, (Berlin: Matthes & Seitz Berlin, 2023), 72–94.

- Cf. Gus Speth and Steve Curwood, Gus Speth calls for a “New” Environtalism, (Interview), 13. February 2015, s. pag., https://loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=15-P13-00007&segmentID=6.

- Cf. https://icewatchparis.com/, 24.03.2023.

- Cf. eg. Hartmut Rosa, Unverfügbarkeit, 8. ed. (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2023) esp. 128–131.

- Cf. https://en.unesco.org/futuresliteracy/about, 24.07.2023.

- Cf. Philip Ursprung, „Earthwards“, 2G, Ensamble Studio, 82, Moisés Puente ed. (Cologne: König, 2021), 4–11.

- Cf. Valerie Hoberg, „Produktive Distanzen. Productive Distances“.

- On contemporary self understandings Buchert, “Inklusiv. Architektur und Kunst“, 9.