Return to archive

title

In Quest of Meaning – Revisiting the discourse around “non-pedigreed” architecture.

author

Vasileios Chanis

Abstract

In their practice, architects never refer to something as “pedigreed” to describe their work. However, during the 1960s, Bernard Rudofsky introduced the term "non-pedigreed" architecture, which he attributed to edifices not designed by formally trained architects, but for various reasons, their status exceeds that of the "mere building". As a fact, since explicit knowledge around “non-pedigreed” architecture is scarce, architects rely mostly on interpretations. This contribution revisits several of these interpretations through the perspective of its "actors," referring to the scholarly work of selected architects, and it is structured into three parts. The first section introduces the motivations behind the study of "non-pedigreed" architecture, delving into questions of aesthetics and authorship. The second part explores the fruitful contradictions arising from the first section and focuses on the relationship between vernacular architecture and the concept of Time, as well as the development of craft skills. Finally, the third part examines specific case studies where the value of vernacular architecture shifts from being merely a reference point to becoming an integral part of the architectural production process.

In his 1958 celebrated movie Mon Oncle, Jacques Tati illustrated the dichotomy between the overregulated Villa Arpel and the preindustrial loose environment found in the district of Le Vieux Saint-Maur. On the one hand, the state-of-the-art designed house incarnates all the principles of the dominant International Style, and on the other, a Parisian neighborhood that represents all that the Modern spirit stood against. The villa consists of the perfect act of rupture against historical continuity; it is a building designed by the sole figure of a pedigreed architect that embraces innovation. On the contrary, the district has nothing to do even with the act of design itself; it is an accumulation of different edifices that count back several generations of builders with no academic training.

Throughout the film, the viewer is repeatedly exposed to their contradictions; the director emphasizes the restrictions that the Villa imposes on its tenants, whose relief comes only in the loose, “non-pedigreed” environment of the old district. While living in the Villa appears to be depressingly comical, life on Le Vieux Saint-Maur seems to fulfill better the needs of human dwelling. By eavesdropping on its time, the film sympathizes with Architecture’s postwar struggle for self-redefinition, implying that responses could be found by examining our anonymous architectural heritage. It is thus representative of a certain “quest” in which “non-pedigreed” architecture plays a meaningful role.

- Figure 1 and Figure 2: Jacques Tati, Mon Oncle, 1958 (Directed and produced by Jacques Tati)

- Figure 1 and Figure 2: Jacques Tati, Mon Oncle, 1958 (Directed and produced by Jacques Tati)

1. DEFINING “NON-PEDIGREED” ARCHITECTURE

Figure 3: Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects, 1964 (moma.org)

Initially, the term “non-pedigreed” architecture was coined by the architect Bernard Rudofksy for the purposes of his influential exhibition “Architecture without Architects”. It is an umbrella term that refers to all those buildings that have not been designed by trained professionals and their construction techniques preceded those of industrialization. Among architects, these examples are commonly known as vernacular architecture, even if the terms are not exactly equivalent

1

The term “vernacular” derives from the Latin “verna” which means “homeborn slave”.

. Rudofsky himself acknowledged the difficulty in definition, stating that “It is so little known that we do not even have a name for it”

2

With the exact words of Rudofsky: “It is so little known that we do not even have a name for it. For want of a generic label, we shall call it vernacular, anonymous, spontaneous, indigenous, rural, as the case may be” (Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1965).

.

In the canonical historiography of architecture, Rudosfky’s exhibition is largely regarded as the official beginning of the field of vernacular architecture studies. With a series of black and white images, he sought to bring MOMA’s visitors in visual contact with buildings and settlements outside the limits of professional architecture. On the opening page, Rudofsky stated:

“Vernacular architecture does not go through fashion cycles. It is nearly immutable, indeed unimprovable, since is serves its purpose to perfection. As a rule, the origin of indigenous building forms and construction methods is lost in the distant past.” 3 Ibid.

One statement, many implications.

In emphasizing the aesthetic purity of architectural design, Rudoskfy shattered two fundamental perceptions that had prevailed in the profession since its inception. Firstly, he rendered invalid Pevsner’s well-known distinction between the bike shed and Lincoln Cathedral, highlighting that both could possess architectural significance

4

I am referring here to the famous quote of Nikolaus Pevsner: “A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture” (Pevsner, Nikolaus. An Outline of European Architecture. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963. p.15.)

. Secondly, he challenged the notion that the production of architecture was solely the domain of architects, emphasizing that it involved a broader range of actors beyond our profession.

Nevertheless, this inclusive shift did not come without any cost. For the purposes of his work, Rudosfky museumify entirely the vernacular, turning an active building tradition of millennia into a passive visual catalogue. He elevated “non-pedigreed” architecture to the status of Art, only by turning it into an exhibit. Moreover, Rudosfky’s purist approach emphasized presenting the vernacular as it had never been exposed to changes; in other words, it was eternal. Thus, not only did he museumify the vernacular, but in order to do so, he flattened down countless years of changes and efforts, failures and successes, into a fixed idealized moment.

A complete erase of the process.

Figure 4: Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects, 1964 (moma.org)

2. A CRITIQUE OF “NON-PEDIGREED” ARCHITECTURE

Despite its position in the canon, Rudosfky’s work is just a small piece of a bigger puzzle. As many recent scholars have stressed

5

I am mostly referring to the recent publications of scholars such as Hilde Heynen, Daniel Maudlin, Carmen Popescu and Marcel Vellinga.

, this “quest for meaning” has its historical roots in the very advent of Modernity, tracing back even to the work of Filarete

6

The reference here is to Filarete’s conception of the “shelter” as a response to the expel from Paradise found in Filate, Antonio. Treatise on Architecture. New Haven: Yale U. Press. 1965 (1465).

. But it is in the troubled aftermath of WWII that the study of “non-pedigreed” architecture became one of the most dominant elements of the architectural discourse. Aiming to a critical exploration of its key aspects, I have chosen to employ the insights offered by specific scholars and philosophers associated often with Phenomenology

7

I am referring here to scholars deriving from the intellectual Tradition of Husserl and Heidegger such as Gilbert Ryle Karsten Harries and Richard Sennet.

. This decision stems from the recognition that their contributions developed alongside the field of vernacular architecture studies, rendering them relevant in this context.

Returning to the aforementioned explanatory definition of “non-pedigreed” architecture, we could distinguish three main important implications deriving from Rudofsky’s approach:

i. Origins and History

8

In his text “Building and the Terror of Time”, Karsten Harries considered “primitivism” or “vernacularism” as an effort of Modernism to find an idealized past as a form of reference. In detail: Harries, Karsten. 1982. ‘Building and the Terror of Time’. Perspecta 19. pp.59–69.

ii. Aesthetics and Representation

9

In his work “The Origins of the Work of Art”, Martin Heidegger criticized the modern tendency towards museumification by claiming that it alienates works of Art from their true content and context. As he characteristically claimed “their relocation in a collection has withdrawn them from their world” (Heidegger, Martin. 2002. Heidegger: Off the Beaten Track. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p.20).

iii. Authorship and Knowledge

In the context of the current text, I will deliberately focus on discussing the third.

It is a fact that architects never refer to their work as “pedigreed.” Furthermore, since the master-builders of “non-pedigreed” architecture, their counterparts, often do not leave behind any testimonies, the availability of explicit knowledge in propositional form is scarce. Consequently, any potential dichotomy between “pedigreed” and “non-pedigreed” architecture becomes a one-way trajectory. Architects acknowledge that they are not the sole producers of architecture, but they reserve the authority to assess what can be deemed as such. From Rudofsky’s perspective, their understanding resides exclusively in the realm of interpretation. This is perhaps why he initially introduced the term “non-pedigreed,” highlighting the absence of clearly defined authorship. But, if there is knowledge embedded within “non-pedigreed” architecture, isn’t it inherently implicit? In any attempt to provide an answer, one should go beyond this definition and challenge the contradictions in the established interpretations. To use Gilbert Ryle’s words, one should emphasize the workshop-possession of knowledge than that of the museum-possession 10 Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.16. .

3. BEYOND “NON-PEDIGREED” ARCHITECTURE

In 1957, seven years before Rudofsky’s exhibition, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy published her seminal book “Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture in North America”. Indisputably, Moholy-Nagy shares many with Rudofsky in terms of line of modern agenda 11 For more information concerning Sibyll Moholy-Nagy’s relationship with the Modern Movement and her decision to embark on the study of American vernacular architecture, please refer to the following: Heynen, Hilde. 2008. ‘Anonymous Architecture as Counter-Image: Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s Perspective on American Vernacular’. The Journal of Architecture 13 (4). pp.469–91. . Nevertheless, her effort in examining the making process of vernacular architecture brought into the foreground several fruitful contradictions. Commenting on two vernacular buildings in the greater area of New England, she wrote the following:

“Within a hundred years, the simple settler had become a highly-skilled craftsman. Stability now comes from the well-constructed quoins of sandstone boulders, set with a high degree of originality and intelligence.” 12 Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl. 1957. Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture in North America. New York: Horizon Press Inc. p.154.

Intentionally or not, Moholy-Nagy questioned the immutability and perfection of vernacular architecture. After all, how can something be eternal, if it evolves through time? And it is precisely this passage of time that elevates the work of the settler, permitting a higher level of originality and intelligence.

In his book “The Craftsman”, Richard Sennet comes exactly to the same conclusion. For him, craft skills could be achieved only through time, not against it

13

Sennett, Richard. 2009. The Craftsman. 1st edition. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

. It is a slow process that despises ruptures. As he argues, explicitly gained knowledge derives from a previous tacit exploration which then, returns back to the Tacit dimension through a repetition in time. For Sennet, this corresponds to the development of skills and as he underlined, “developing a skill, means to learn many ways to perform the same activity”

14

Sennett, Richard. 2016. ‘Craftsmanship’. Lecture at Museum für angewandte Kunst – Wien, 44:56. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIq4w9brxTk, last accessed at April 20, 2023.

. Viewed from this perspective, “non-pedigreed” architecture is actually a craft, meaning a process through which someone develops certain skills. Then how can architects really develop them?

4. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW PARADIGM

- Figure 5: The Bavra school under construction, Gujarat 1961 (The Christopher Alexander & Center for Environmental Structure Archive)

- Figure 6: The Bavra school under construction, Gujarat 1961 (The Christopher Alexander & Center for Environmental Structure Archive)

One first answer came in 1964, the exact same year of Rudofsky’s publication. It was then that Christopher Alexander published his PhD Thesis with the revisited title “Notes on the Synthesis of Form”

15

Christopher Alexander was the first ever PhD student in Architecture at Harvard University. In 1963, he was awarded the doctoral degree for his thesis ‘The synthesis of form; some notes on a theory’ under the supervision of Serge Chermayeff. This is the original document that later will be published as ‘Notes on the Synthesis of Form’: https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=01HVD_ALMA211882071160003941&context=L&vid=HVD2&lang=en_US&search_scope=everything&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=everything&query=lsr01,contains,990037347430203941&mode=basic&offset=0,last accessed at April 20, 2023.

. Alexander’s doctoral work is distanced from the Modern perspective while his research contained precious observations for the development of a new paradigm for the process of making architecture.

In his treaty, Alexander avoided the use of any established terms that emphasize authorship; there is no use of adjectives such as vernacular, anonymous and of course, “non-pedigreed”. On the contrary, he stressed the importance of the process which he divided into two main categories: the unselfconscious and the self-conscious

16

Alexander, Christopher. 1964. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, Mass. pp. 46-70.

. Very briefly, the unselfconscious process relies much on the power of tradition and craft skills, while the self-conscious one is built upon the authorship of the individual. Historically speaking, the first transition from one to the other happened during the Renaissance. But this passage signified a certain “loss of innocence”. Due to his self-recognition, the artist/architect has now a deep effect on the process of form-making, raising thus a series of new questions. Alexander characteristically underlined:

“To achieve in a few hours at the drawing board what once took centuries of adaptation and development, to invent a form suddenly which clearly fits its context – the extent of the invention necessary is beyond the average designer.” 17 Ibid. p.59.

Alexander did not believe that a return to the unselfconscious process is attainable; he was against nostalgia. But instead, he fundamentally believed that architects are obliged to regain a certain control over the actual process of building; thus, a certain level of craft skills.

Alexander practiced what he preached in the second part of his PhD with the analysis of the village of Bavra in Gujarat, India

18

Among the scholars of his work, this project is known for its original mathematical treatment, as well as for the diagrams that Alexander developed and that they were the prelude to his magnum opus “A Pattern Language”.

. In 1961 he travelled to India and spent seven months among the local population of the village. It is there where he was asked to build a new school with a very limited budget at his disposal. This is how he tackled his lack of workshop-possessed knowledge and he began developing his craft skills. And the result vindicated him.

As these original pictures demonstrate, Alexander worked in direct collaboration with the local population. As he claimed: “This was my start in architecture. It was the first building I ever made and the first time I invented anything in construction”

19

Alexander, Christopher. 2020. The Nature of Order, Book 3: A Vision of A Living World: An Essay on the Art of Building and The Nature of the Universe. The Center for Environmental Structure. pp. 526-527.

. By using the abundant mud and clay of the area together with the expertise of the local potter, Alexander came up with an innovative solution that solved the problem of the roof span of the school. This came in the form of the conical “guna” tiles that he assembled inside the other.

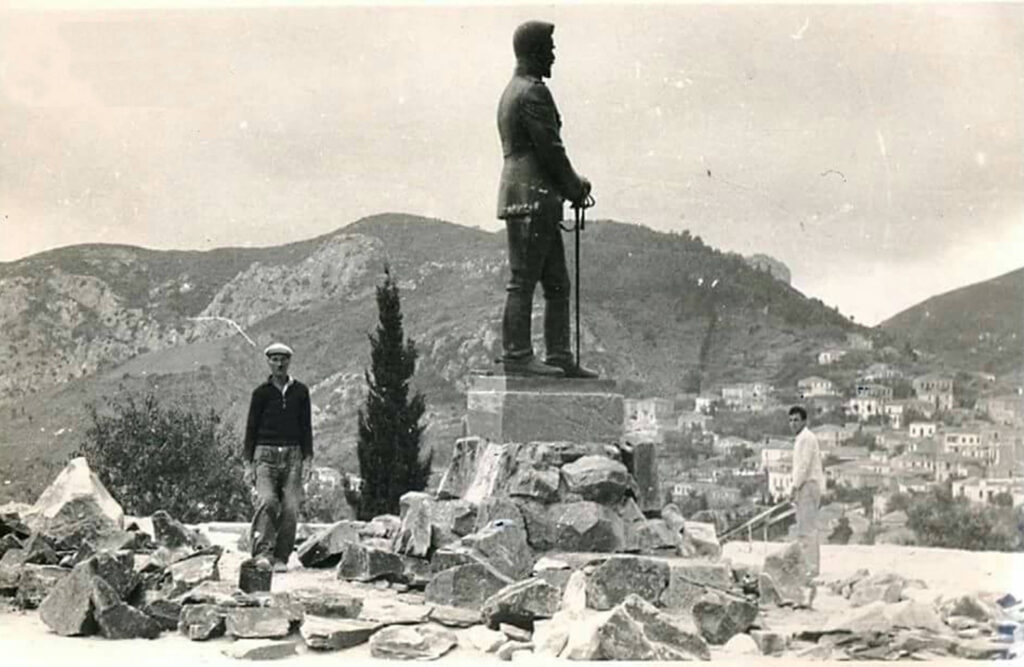

Figure 7: Dimitris Pikionis, his students, and the local craftsmen at work, Kymi 1961 (Archive of Agni Pikioni)

Figure 8: Dimitris Pikionis, his students, and the local craftsmen at work, Kymi 1961 (Archive of Agni Pikioni)

Nevertheless, Alexander was not the first example of an architect who admired the vernacular “knowing-how” of the building site and prioritized it against the “knowing-that” of the drawing board 20 Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.16. . I would like to draw attention to the works of one more architect who is known for his similar approach. I am referring to Dimitris Pikionis and specifically here I would like to discuss his last project; a small memorial dedicated to a fallen military hero. The project was commissioned to Pikionis in the same year and was executed exclusively in situ. His strategy was the reuse of the material found in the nearby threshing floor in order to construct the new interventions and the pedestal of the statue. From the pictures, we can see Pikionis working on the site with the local craftsmen and with the help of selected assistants. No prior preparation was made and no drawings were produced as they collectively negotiated every step on the site. They even worked the stones themselves, carving the new and repairing the old. What I consider crucial to highlight in both is that their method of work bears resemblance to the old diptych of “master-apprentice”. And as Polanyi explained, this constitutes a form of collaboration that is representative of the tacit transmission of knowledge, mainly through the imitation of physical gestures 21 Polanyi, Michael. 1974. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. First Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.53. .

EPILOGUE

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize what I consider to be the most significant aspect of Alexander’s argumentation compared to that of Rudofksy. As previously discussed, the issue of authorship holds a central position in the perspectives of both. However, it appears that for Alexander, authorship throughout the building process holds greater importance than the final built outcome. Although more malleable, this emphasis allows for the development of specific skills that cannot be acquired through other means. It serves as a medium through which architectural knowledge, rooted in the Tacit dimension, becomes tangible. At the same time, it reduces the sense of experiential alienation that architects often feel at the worksite and enables them to rediscover the lost sense of the “here and now” 22 I am referring here to the meaning of “here and now” in the way Walter Benjamin described it in his text “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935). of their Art. Both Alexander and Pikionis were pioneers in the exchanges between the vernacular “modus operandi” 23 Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.3. and the discipline of architecture; this was in my point of view their quest for meaning. In their projects, they did not strive for novelty nor for the expression of their individual personality. Instead, they functioned as mediators in the restoration of a new architectural Tradition—; a Tradition in which personal knowledge will be produced with great labour 24 This is a reference to Thomas Eliot’s quote that “Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour”. For more information: Morrissey, Lee. 2005. ‘T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” The Sacred Wood (1919)’. In Debating the Canon: A Reader from Addison to Nafisi, edited by Lee Morrissey, 29–34. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-04916-2_7. , but society will be always willing to preserve a great fund of it 25 This is a reference to Michael Polanyi’s quote that “A society which wants to preserve a fund of personal knowledge must submit to tradition”. For more information: Polanyi, Michael. 1974. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. First Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.53. . And this is because architects will be once again the ones who lead a collective endeavour with no desire to be imposed on it.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 945363.

It is also supported by a doctoral grant from the Sophie Afenduli Foundation.

- The term “vernacular” derives from the Latin “verna” which means “homeborn slave”.

- With the exact words of Rudofsky: “It is so little known that we do not even have a name for it. For want of a generic label, we shall call it vernacular, anonymous, spontaneous, indigenous, rural, as the case may be” (Rudofsky, Bernard. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, 1965).

- Ibid.

- I am referring here to the famous quote of Nikolaus Pevsner: “A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture” (Pevsner, Nikolaus. An Outline of European Architecture. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963. p.15.)

- I am mostly referring to the recent publications of scholars such as Hilde Heynen, Daniel Maudlin, Carmen Popescu and Marcel Vellinga.

- The reference here is to Filarete’s conception of the “shelter” as a response to the expel from Paradise found in Filate, Antonio. Treatise on Architecture. New Haven: Yale U. Press. 1965 (1465).

- I am referring here to scholars deriving from the intellectual Tradition of Husserl and Heidegger such as Gilbert Ryle Karsten Harries and Richard Sennet.

- In his text “Building and the Terror of Time”, Karsten Harries considered “primitivism” or “vernacularism” as an effort of Modernism to find an idealized past as a form of reference. In detail: Harries, Karsten. 1982. ‘Building and the Terror of Time’. Perspecta 19. pp.59–69.

- In his work “The Origins of the Work of Art”, Martin Heidegger criticized the modern tendency towards museumification by claiming that it alienates works of Art from their true content and context. As he characteristically claimed “their relocation in a collection has withdrawn them from their world” (Heidegger, Martin. 2002. Heidegger: Off the Beaten Track. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p.20).

- Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.16.

- For more information concerning Sibyll Moholy-Nagy’s relationship with the Modern Movement and her decision to embark on the study of American vernacular architecture, please refer to the following: Heynen, Hilde. 2008. ‘Anonymous Architecture as Counter-Image: Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s Perspective on American Vernacular’. The Journal of Architecture 13 (4). pp.469–91.

- Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl. 1957. Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture in North America. New York: Horizon Press Inc. p.154.

- Sennett, Richard. 2009. The Craftsman. 1st edition. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

- Sennett, Richard. 2016. ‘Craftsmanship’. Lecture at Museum für angewandte Kunst – Wien, 44:56. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIq4w9brxTk, last accessed at April 20, 2023.

- Christopher Alexander was the first ever PhD student in Architecture at Harvard University. In 1963, he was awarded the doctoral degree for his thesis ‘The synthesis of form; some notes on a theory’ under the supervision of Serge Chermayeff. This is the original document that later will be published as ‘Notes on the Synthesis of Form’: https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=01HVD_ALMA211882071160003941&context=L&vid=HVD2&lang=en_US&search_scope=everything&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=everything&query=lsr01,contains,990037347430203941&mode=basic&offset=0,last accessed at April 20, 2023.

- Alexander, Christopher. 1964. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, Mass. pp. 46-70.

- Ibid. p.59.

- Among the scholars of his work, this project is known for its original mathematical treatment, as well as for the diagrams that Alexander developed and that they were the prelude to his magnum opus “A Pattern Language”.

- Alexander, Christopher. 2020. The Nature of Order, Book 3: A Vision of A Living World: An Essay on the Art of Building and The Nature of the Universe. The Center for Environmental Structure. pp. 526-527.

- Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.16.

- Polanyi, Michael. 1974. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. First Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.53.

- I am referring here to the meaning of “here and now” in the way Walter Benjamin described it in his text “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935).

- Ryle, Gilbert. 1945. ‘Knowing How and Knowing That: The Presidential Address’. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 46. p.3.

- This is a reference to Thomas Eliot’s quote that “Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour”. For more information: Morrissey, Lee. 2005. ‘T.S. Eliot (1888–1965) “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” The Sacred Wood (1919)’. In Debating the Canon: A Reader from Addison to Nafisi, edited by Lee Morrissey, 29–34. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-04916-2_7.

- This is a reference to Michael Polanyi’s quote that “A society which wants to preserve a fund of personal knowledge must submit to tradition”. For more information: Polanyi, Michael. 1974. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. First Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.53.