Return to archive

title

Presence, Presentation & Representation Between Model Making and Mediation of Material in Architectural Practice during Covid-19

author

Mara Trübenbach

Abstract

This paper presents one specific action, i.e. a remote empirical research within a PhD project embedded in the international research network “TACK: Communities of Tacit Knowledge: Architecture and its Ways if Knowing”. The aim of the digital ethnography was to understand processes and dynamics in an architectural office in relation to new conceptualizations of the material. In asking questions about the subject in the current pandemic context, the question of the media of such an enquiry was implicated in the thesis developed. On the one side, this study is both about finding a platform on which to discuss the idea of material, and is a speculation about the implication of that platform for the ideas developed using it. On the other, it deals with using an opportunity provided by Covid-19 to make that research, via a remote ethnography with the implication that this might be used to research lots of other things beyond materials. The study hopes to create a platform for discussion around researching, observing and mediating material ¬– revising understanding as well as increasing material literacy – beyond Covid-19.

In this paper one specific action, i.e. a remote empirical research within the dissertation project Material Orbit. A Rendering of Rituals, Decay and Trails of Dust in the Architectural Design Process (AHO, Oslo) is presented. The aim of the study was to understand processes and dynamics in an architectural office in relation to new conceptualizations of the material. In asking questions about the subject in the current context (Covid-19), the question of the media of such an enquiry was implicated in the thesis developed. On the one side, this paper is both about finding a platform on which to discuss the idea of material, and is a speculation about the implication of that platform for the ideas developed using it. On the other, the project hopes to create a platform for discussion around researching, observing and mediating material ¬– and revising understanding as well as Increasing material literacy – beyond Covid-19. The stake of different images used in this paper, represents the different types of statements embedded. Moreover, the study’s job is the reflected account of what I (ESR) actually did, expected and its further use for the PhD project. However, since the digital ethnography is part of a broader study, this paper contemplates a limited description.

The paper deals with using an opportunity provided by Covid-19 to make that research, via a digital ethnography with the implication that this might be used to research lots of other things beyond materials. Not only used as a research method but as a participative subfield in people’s everyday life to decentralize the “digital” within the digital 1 Pink, Sarah (2016): “Experience”, in: Sebastian Kubitschko & Anne Kaun (Ed.), Innovative Methods in Media and Communication Research, (eBook), Cham, CH: Springer Nature, p. 161-165. . Rather than focusing the study around a single architectural work, and mapping all the actors and influences on that “work” the strategy changed to focus instead on the trajectories of figures who traditionally would be thought of as having peripheral impact on the design of work – in this case one female model maker who worked across architectural teams within the practice. Thus, the enquiry became more precise in relation to labor agency 2 Tsing, Anna (2013): “Sorting out Commodities: How Capitalist Value Is Made through Gifts”, in: HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (1), pp. 21–43. i.e., the ethnographic study at London-based architecture practice HaworthTompkins (HT), relates to two approaches of the research: material systems and the issue of how architecture is valued via mediated concepts. It builds upon HT’s in-house model maker Ellie Sampson and the firm’s understanding of material. According to Albena Yaneva’s ethnography of the Rotterdam-based architectural firm OMA, there is a lack of missing out „social phenomena“ i.e., the process of making in the architectural discourse 3 Yaneva, Albena (2009): Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design, Rotterdam, NL: 010 Publisher. . Finally, the study hopes to contribute to the developments of finding alternative research methods within an evolution of digitized work habitats in both contemporary architecture practice and research.

Remote workshop and the invention of “Digital Mara”

The first main part of the ethnographic study dealt with how the model maker Ellie Sampson works and the collaborative process around it. The best thing to contextualize Ellie’s role is to picture HT’s workshop, which is located in the heart of the office and invites you to swing by, chat and point to models, materials and tools. The workshop not only serves as a productive place, but also generates a social environment for HT’s staff. By observing advices/critics, photos of process and interviews with the model maker, my ambition was to examine the (tacit) knowledge in model planning itself i.e. drawings e.g. for laser cutter, considering material thickness, mocking-up 3d CAD models and logistics for instance use, storage, relocation. This intention turned out to become a three-folded operation. First, starting with the knowledge of Ellie’s internal process and her craft world – creation of drawings and mediations in the production of the model. Second, going further with Ellie’s work in a broader operation in the practice as whole and her enrichment in the design team i.e., thinking through the design by talking to and interacting with Ellie on different levels. Third, the expertise in the practice of HaworthTompkins as a whole interacted with its environment.

The initial undefined idea of simulating a more active perspective like a Go-pro was soon implemented as a fun operation called “Digital Mara”, which introduces ‘vlogging’ almost as a research method. The physical transfer of myself, the scholar, had been assisted by a communication service tool – a black iPad in its 7th generation with a high-impact polycarbonate shell slipcover which travels via Norwegian post to Great Britain. Although it might be seen as ironic to investigate material matters without being able to physically attend the scene of the crime, this device offered a kind of material presence (covered with a haptic material it had to be unpacked and adopted by whichever staff member was hosting it) as well as, in its inert quietness and its machine dumbness, providing a fly-on-the-wall-view that could not be achieved through physical presence. The technical devise served as an experiment in research methods. Besides the stage reports and meetings, I joined Ellie for an extended session of 3-4 hours once a week, to get a hands-on perspective and watch how Ellie laser-cuts or assembles and glues pieces. This observation would run simultaneously while working on other stuff. Very similar to a co-working space, only digital. Both would be muted, listen to music and if there were questions, we would rase hand and interrupt each other.

Beneath the discovered digital surface of materiality

A few months back, while Ellie was demonstrating the various machines during a workshop induction to a new staff member, I remember hearing noises of machines and wanting to be there in person, too. This primarily is due to my background in architectural education and strong interest in craft, I guess. Principally I missed the other sensorial experiences I know would have been present in the room itself. Behind that digital surface of a clear glass LCD screen, I could only guess how the reaction of materials to the different operations would, for instance, smell. This happened actually quite often – hearing Ellie milling, sanding, spraying or laser-cutting and not being able to smell the freshly cut pieces. If I hadn’t experienced being in a workshop before, I wouldn’t know what is missed in the sense of smelling finished material. This memorable moment that is attached to different senses deeply highlights the difficulty of engagement in a digital study. As senses are part of architect’s knowledge, without even knowing so, they are embodied thinkers 4 Pallasmaa, Juhani (2009): “The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture”, Chichester, UK: AD Primers. . Nevertheless, “Digital Mara” served fairly sufficiently as representation for being on site. It actually raises awareness of the importance of “structures of feelings” embedded in the editing and writing process of the oral history 5 Gosseye, Janina, Naomi Stead, and Deborah Van der Plaat (2019): Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research., (1st Ed.), New York, US: Princeton Architectural Press. . I had the feeling that, regardless of whether it was taking pictures, working on machines or assembling parts, Ellie took “Digital Mara” with her, and thus, allowed me a perspective of being part of the whole process. My perception that is based on almost neutralized senses – perhaps one sees more when not drunk on the smell of laser-cut paper – leads to the methodological implication that because of certain limitations of sensation it opens up possibly opportunities in other directions of tacit knowledge in relation to material.

The new circumstances and the importance of the medium of visualization in digital environments in the office have also a big impact on the way Ellie works and communicates with her colleagues indeed. It reflects on both relationship between language and things, and the knowledge of transfer with and through material 6 Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015): “Objektstunden. Vom Materialwissen zur Materialbildung.”, In: Herbert Kalthoff, Torsten Cress, Tobias Röhl (Hg.), Materialität. Herausforderungen Für Die Sozial- Und Kulturwissenschaften, Paderborn, DE: Fink Verlag, pp. 171–193. .

Ellie said: “Corona virus and people working from home has led to more formalization of how the procedures of model making work in the office. Because you have to be more prepared. But not just prepared for what you are showing people, [but in terms of] samples, processes within the office as in making sure and checking with people that the laser-cutting is finalized before I cut it. Because they are not there to give me a kind of on-the-ground feedback. It has also formalized elements like ordering materials, because it takes longer to have things delivered, sometimes they don’t have things in stock, certain places are not open all the time. Those practicalities have changed the process a lot more. So, I now collect like shopping lists in a more thought-through way. I group together projects to make sure that we have all of the material ready for people. I think in general, […] throughout my time as model maker at HT, it always helps to be more prepared, particularly with the project like the Warburg […]. Overall, I haven’t noticed it’s being less efficient. I think, […] for me anyway working in this way, has shown people the need for a bit more time to prepare […]. There have to be compromises. Normally, before lockdown, time was the compromise.” 7 Sampson, Ellie. Personal interview “Zoom Interview”, 10th Oct 2020.

These kind of changed modes of practice in which a digital screen is being inserted between actors communicating within the practice make visible other issues that lie beneath the surface of such interactions and that are close to my empirical study subject. One concern precisely the way in which the practice thinks about materials, materials choice, and the communication of these choices to clients and consultants before the building is constructed.

Mediating material literacy

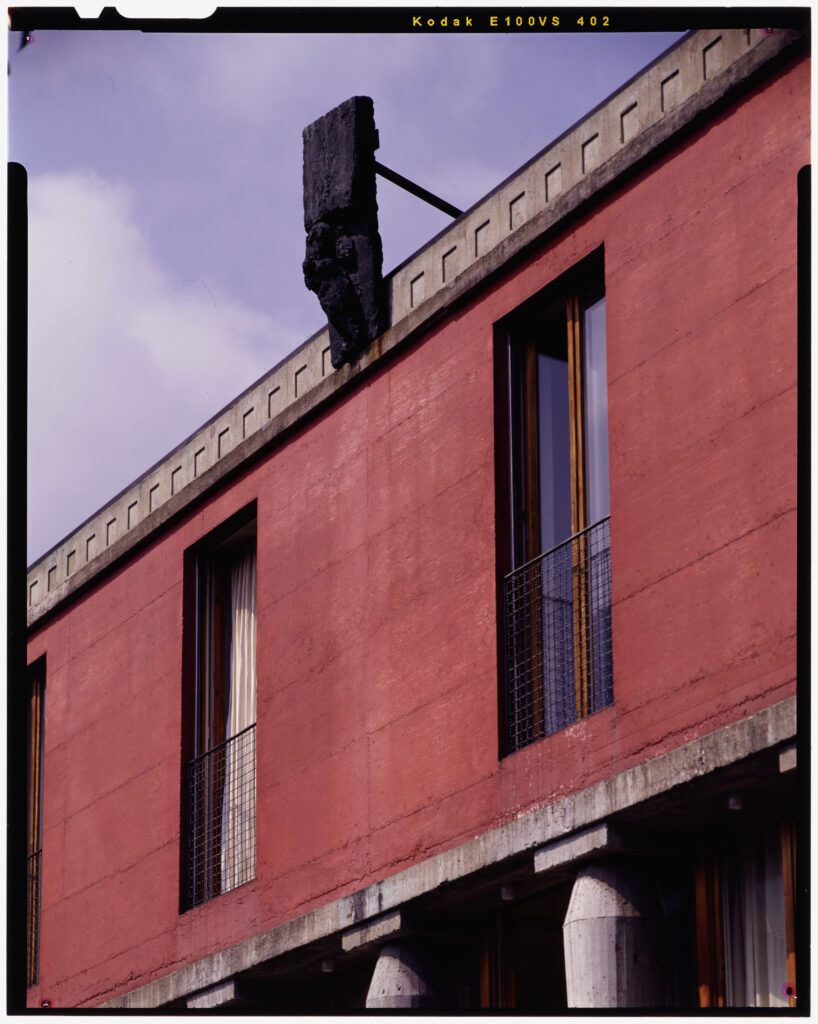

The latest model for the “Warburg Renaissance” project was made by Ellie just when the lockdown started in March. Although her living room became temporarily HT’s new workshop, she could not completely finish the model and some parts still have to be re-done. The process begins by discussing needs and wants of the architects. Based on a prepared document from Ellie on the presentation of material, the design team talked about which option they like best. It gets clear fairly quickly that the explanation of material i.e., the verbal language becomes a requirement to communicate features of physicality. Especially, if the communication partner does not know the material and bits gets lost by translating physical experience to verbal language. The space and physical objects should not be seen distinct as both interact with each other and influence the perception 8 Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1948): The World of Perception., (Translated by Oliver Davis), Oxford, UK; New York, US: Routledge. . Furthermore, this verbalization inverses the discussion from the outside towards the inside and emphasizes the “emancipatory potential of discourse” which occurs when insider knowledge and outsider views meet 9 Kockelkorn, Anne (2019): “Uncanny Theatre – A Postmodernist Housing Play in Paris’s Banlieues, 1972 – 1992. In Productive Universals Specific Situations”, in: Anne Kockelkorn and Nina Zschocke (Eds.), Berlin, DE: Sternberger Press, pp. 336–81. . Ellie said this has increased her understanding of material a lot and that she “need[s] to talk about it in a different way” 10 Sampson, Ellie. Personal interview “Zoom Interview”, 10th Oct 2020. . The importance of representation, reality and the mediation of material becomes even more crucial when they talk about the fact that they cannot decide about all material online, because they simply don’t know what it looks like in reality. This identifies a lack of clarity by architects when it comes to formulate architectural ideas and not being able to get an embodied consciousness 11 Pérez-Gómez, Alberto (1987): “Architecture as Embodied Knowledge.”, in: Journal of Architectural Education 40 (2), pp. 57–58. .

Another aspect is the trial to keep the material as realistic as possible to avoid photoshopping of colour and light later, but still consider Photoshop as a tool for representation. The photoshopping occurs by the presentation images of models that are the only possibility to currently engage with them. The main destination of models now is as images as opposed to as physical objects. Furthermore, there are discussions about what angle of photo is wanted in order to fit the model for that certain perspective. This participatory method and relationship between people and artificial world regard the act of photography rather as a “form of question than a statement of apparent fact” 12 Bremner, Craig, and Mark Roxburgh (2015): “A Photograph Is Evidence of Nothing but Itself.”, in: The Routledge Companion to Design Research, London, UK; New York, US: Routledge, pp. 203-214. . Former CGI’s made in Sketch-UP and digital plans serve both as a reference and as an orientation to take shots from. Ellie once mentioned, she is not a professional photographer. Noticeable though that a lot of time is spent on taking pictures of her models either to present to clients and staff, or to compare to older design versions. There is almost a typical order of building a model, taking pictures and changing afterwards in Photoshop. Ellie’s tacit knowledge of the model’s features probably helps her to shed light on when shooting. The images are also part of HT’s Instagram account. This represents on the one hand Ellie’s process of work, and on the other it has a huge impact on the discussion around mediated material in the digital community. There is a lack in experiencing and interpretating nowadays as we differently engage with the building or site than before social media 13 Mahmoudi Farahani, Leila, Motamed, Bahareh and Ghadirinia, Maedeh (2018): “Investigating Heritage Sites through the Lens of Social Media.”, in: Paul A.Rodgers and Joyce Yee (Ed.), Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 42 (2), Oxon, US; New York, US: Routledge, pp. 188–98. . According to Farahani, Motamed and Ghadirinia, this gap needs to be acknowledged and critically reflected when heritage sites – or as in this case materials – are mediated and, in some cases, manipulated by editing pictures.

The digital ethnography is reflected as an experiment, providing opportunities and limitations within the method. One of the main lack is the missing informal conversation between Ellie, her team and me, which would happen during lunch break or door-to-door chats. Of course, another very important aspect is the absence of sensational experience – intuitive engagement with the model and materials – accompanied by the limited view of the transmitted happening due to a narrow angle of the camera. Despite all this, a great alternative window in relation to my wider aim of the PhD project to investigate how materials are conceptualized in architectural practice opened, which would not have happened in this way if there was no digital but personal observation. It unfolds conversations that would be invisible otherwise because they would not need to be screeded. Communication is not only a soft skill anymore but becomes, besides mediation, a reinforced instrument that has been strongly trained since online events are part of the daily architectural practice. What kind of vocabulary is used not only sheds light on how language can become a transformational tool in design processes, but also makes aware of the distinction between material literacy. Even though it takes more time to forensically prepare the design and model process stages, consultations become more efficient in terms of being precise while discussing the design and explaining materials. By engaging with the case study, the research takes into account the environment surrounding the material matters i.e. implications and agencies of material application. The remote ethnographic study hopes to unfold the potential of how to get inside a sealed box i.e., architectural practice and to bring aspects of tacit knowledge of a model maker to life. Moreover, the PhD project will benefit from the great work and expertise of Ellie and her colleagues and will include insights and reflection of the remote work in architectural practice.

- Pink, Sarah (2016): “Experience”, in: Sebastian Kubitschko & Anne Kaun (Ed.), Innovative Methods in Media and Communication Research, (eBook), Cham, CH: Springer Nature, p. 161-165.

- Tsing, Anna (2013): “Sorting out Commodities: How Capitalist Value Is Made through Gifts”, in: HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (1), pp. 21–43.

- Yaneva, Albena (2009): Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design, Rotterdam, NL: 010 Publisher.

- Pallasmaa, Juhani (2009): “The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture”, Chichester, UK: AD Primers.

- Gosseye, Janina, Naomi Stead, and Deborah Van der Plaat (2019): Speaking of Buildings: Oral History in Architectural Research., (1st Ed.), New York, US: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015): “Objektstunden. Vom Materialwissen zur Materialbildung.”, In: Herbert Kalthoff, Torsten Cress, Tobias Röhl (Hg.), Materialität. Herausforderungen Für Die Sozial- Und Kulturwissenschaften, Paderborn, DE: Fink Verlag, pp. 171–193.

- Sampson, Ellie. Personal interview “Zoom Interview”, 10th Oct 2020.

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1948): The World of Perception., (Translated by Oliver Davis), Oxford, UK; New York, US: Routledge.

- Kockelkorn, Anne (2019): “Uncanny Theatre – A Postmodernist Housing Play in Paris’s Banlieues, 1972 – 1992. In Productive Universals Specific Situations”, in: Anne Kockelkorn and Nina Zschocke (Eds.), Berlin, DE: Sternberger Press, pp. 336–81.

- Sampson, Ellie. Personal interview “Zoom Interview”, 10th Oct 2020.

- Pérez-Gómez, Alberto (1987): “Architecture as Embodied Knowledge.”, in: Journal of Architectural Education 40 (2), pp. 57–58.

- Bremner, Craig, and Mark Roxburgh (2015): “A Photograph Is Evidence of Nothing but Itself.”, in: The Routledge Companion to Design Research, London, UK; New York, US: Routledge, pp. 203-214.

- Mahmoudi Farahani, Leila, Motamed, Bahareh and Ghadirinia, Maedeh (2018): “Investigating Heritage Sites through the Lens of Social Media.”, in: Paul A.Rodgers and Joyce Yee (Ed.), Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 42 (2), Oxon, US; New York, US: Routledge, pp. 188–98.