Return to archive

title

Dissemination of Architectural Culture: A View on Turkish Architects’ Journeys in the Pre-Digital Age

Author

Ceren Hamiloglu

supervised by

Ahsen Özsoy

Abstract

An architect is an intellectual person who develops a professional architectural identity and approach through an accumulation of their personal experiences, education and knowledge. Perhaps the most pivotal part in an architect’s ‘formation journey’ is the initial years they start constructing their architectural selfhood. The initial years in which a person “becomes” an architect, are signified by the mobility of young architects, ideas and encounters, through which an architecture culture forms and disseminates. The dissemination of ideas is facilitated through institutions, visual, verbal and textual representations. Traveling, with its ability to embody all of these components appears to be a fruitful practice through which architecture culture can be analyzed. During the twentieth century, new encounters provided a ground from which Turkish-speaking architects established a firmer professional position and disseminated new implementations in the architecture field. The purpose of this research is to understand how Turkish-speaking architects’ journeys in the pre-digital age, contributed to the period’s architectural discourse in Turkey. Therefore, the ways in which architects traveled, translated and disseminated their travel experiences were studied and evaluated through content analysis.

Introduction

Traveling, when described as transposition or relocation and encounter with a new place or context, is innate and still relevant to the architecture discipline. Academic Joan Ockman defines architect-travelers as “active” gazers who are able to “see by means of theorizing” and affirms the explosive effect of physical encounters during journeys.

1

Joan Ockman, “Bestride the World Like a Colossus: The Architect as Tourist” in Joan Ockman and Salomon Frausto, ed., Architourism: Authentic, Escapist, Exotic, Spectacular” (Munich: Prestel, 2005), pp. 158-185 (p. 161).

Surely, traveling or its representational scatters do not have the same effect today: the internet attenuated the necessity of transferring physical travel experiences.

However, until it became a mundane part of a hyper-mobile and digitalized world, traveling abroad to study and/or to inspect the architectural production of other -especially western- countries was valued so profoundly in Turkey, that successful architecture students were awarded with scholarships by the government to study and intern in countries such as Germany, Switzerland and France. These scholarships were offered to contribute to the efficacy of repositioning Turkey in the global scene, as well as modernizing the society. The 1416 legislation of sending students to foreign countries that came into force in 1929 demonstrates the first attempt in regulating students traveling abroad for education. Despite WWII, the number of students studying abroad increased every year. Germany –especially Stuttgart Architecture School- was the most frequent destination for Turkish-speaking architects between 1930-1960.

2

Emine Seda Kayım, “1920-1960: İstanbul – Stuttgart Hattı Kemali Söylemezoğlu’nun Kariyeri Üzerinden Türk-Alman Mimarlık İlişkilerini Okumak”, Unpublished Phd thesis (Istanbul: Yıldız Technical University, 2010).

Stuttgart was an intersection point for key figures who affected the architectural culture in Turkey: Paul Bonatz, Rolf Gutbrod, Hans Poelzig and Martin Elsaesser were all affiliated with the University of Stuttgart and either taught courses at universities or participated in architectural projects in Turkey. Especially until the 1950s, due to the Turkish state’s militaristic history and the presence of German academics in Turkey, there was a close affinity to German architecture culture.

Modern Turkey was founded on European notions of modernity and prosperity under the leadership of Kemal Atatürk. Especially in the first years following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, many architecture students studied, did internships or “study trips” in other countries to gain contemporary knowledge on architectural issues. Some of these study trips were funded by Turkish architecture journals and institutions (mostly the universities) until the 1970s. But why did Turkish architects travel? What did they bring back from their journeys? How did they choose to disseminate their experiences? To answer these questions, I turn to tacit knowledge, which cannot be easily explained through words and make up a considerable portion of the architectural discipline. Aspects of creativity, conveying feelings through spaces or finding niche solutions, in other words, the practicing of the discipline has large bearing on personal knowledge. According to Michael Polanyi, “personal knowledge”, which is gained through personal participation and practice, facilitates one’s ability to contact reality beyond the theories one relies on.

3

Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (New York: Harper & Row, 1964), 63-64.

This research aims to demonstrate that through their personal knowledges, Turkish architects used physical traveling as a means to materialize their knowledge, experience and new encounters before internet became wide-spread. Combined with oral history, unstructured interviews and memoirs; a group of architects, their trips and travel representations were analyzed as translations from tacit to explicit knowledge, or knowledge that could systematically disseminate.

The ways in which architects traveled was tied to their previous -visual, textual or verbal- encounters within the architecture discipline. Especially during journeys in the 1930s-40s, Turkish architects mostly focused on gaining a certain “know how” in relation to their existing architectural knowledge. Secondly, the “shock” of mobility had a productively triggering effect on architects: they often wrote about or lectured on their trips after they returned. To demonstrate this, I reflect on architects such as Seyfi Arkan, Şevki Balmumcu and Hulusi Güngçr who went on study trips and systematically produced articles or books with the knowledge they gained through them and the networks in which architects such as Ersen Gürsel, Muammer Onat, Orhan Şahinler and Doğan Kuban shared a similar architectural knowledge and culture.

This article focuses on the kind of tacit knowledge that is embodied, gained through personal experience by being on site and generating personal knowledge through translating that experience into an oral, visual or textual form. The only way in which architects’ travel experiences could systematically circle back into the architectural debates of the period, was through translation and materialization: as architects translated their “on-site” experiences into “off-site” representations (photographs, articles, lectures, class notes and memoirs), the embodied knowledge that was acquired on site, met an audience and disseminate as explicit knowledge.

“Acquired” Architectural Knowledge

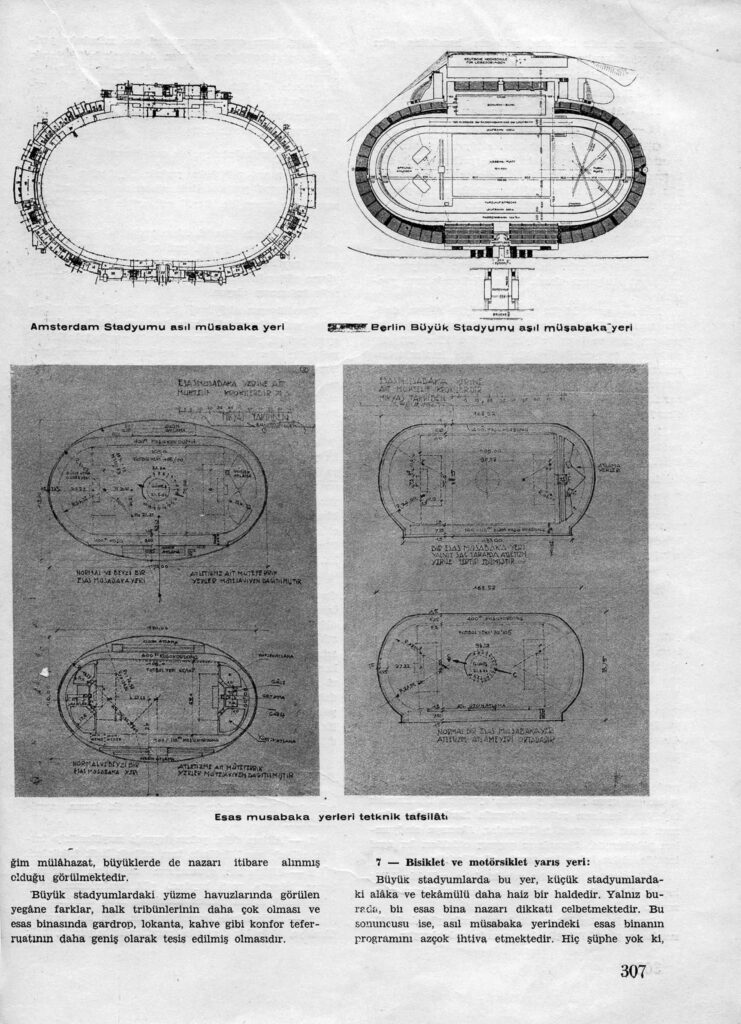

Figure 1: Page showing the plans and drawings of Amsterdam and Berlin Stadiums. Source: Seyfettin Nasıh, ‘Stadyumlar: Almanya Stadyumları Hakkında Bir Tetkin Raporu [Stadiums: A Study Report on German Stadiums]’, Arkitekt, 33-34 (1933), 307.

These architects share a similar writing tone that is detailed, straightforward and descriptive of places, exhibitions and buildings. They were aiming at delivering what they acquired on site, that is, what directly lay in front of their eyes and the history behind it. The trips to Europe demonstrate the firm belief in Europe as the idealized location for cultivation and a site of static knowledge which is waiting to be acquired and delivered by an architectural figure. Architect Jilly Traganou asserts that the fascination with architectural journeys is based on the tendency that associates traveling with epistemology and the potential in mobility to provide insight. 7 Jilly Traganou, “For a Theory of Travel in Architectural Studies”, in Jilly Traganou and Miodrag Mitrasinovic, ed., Travel, Space, Architecture(Surrey: Ashgate, 2009), 4-26 (p. 5). Historically, in various cultural and religious beliefs, traveling and mobility was used as a means of having distance from home, getting closer to “the other”, as well as to oneself, and finding new knowledge and wealth in an unknown territory. 8 Winfried Löschburg, Seyahatin Kültür Tarihi [Kleine Kulturgeschichte des Reisens], translated by Jasmin Traub (Ankara: Dost Kitabevi Yayınları, 1998), 7-9. Despite the modernist fascination with movement and distance, undesired displacement and migration is the reality of most of the mobility occurring today. 9 Caren Kaplan, Questions of Travel: Postmodern Discourses of Displacement (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 23-25. Historically, traveling has maintained a position of home, destination, traveller and ‘the other’ and established a hierarchy between them. Dominant historical narratives focus on architects’ travels from the imperial centre to the colonial periphery. 10 Julie Willis, “Architectural Movements: Journeys of an Intercolonial Profession”, Fabrication 26, 2 (2016), 158-179 (p. 158).

In a number of memoirs, architects make a distinction between their trips within Turkey and those abroad. The former is often described as an act of “getting to know” or learn more about the “motherland”, while the latter consists of visiting examples of modernist architecture to gain know-how and to expand one’s personal knowledge on design. In Turkish architectural culture of the 1930s and 40s, Europe was a destination where well-designed buildings and settings could be encountered and internalized as part of the architect’s “individual repertoire”.

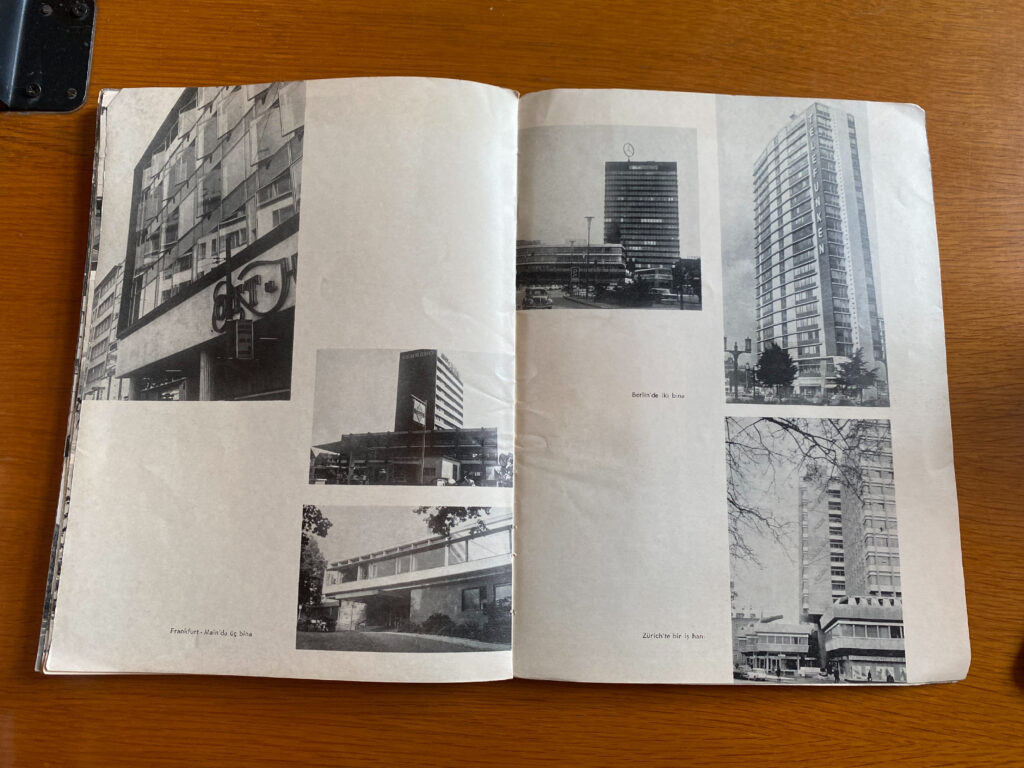

Figure 2 Pages from Hulusi Güngör’s How to Build Cities, Istanbul, 1969.

Academic Margitta Buchert elaborated “the individual repertoire” as acquired by perceptions, actions and memories, and involved “individual capabilities” defined by experiences such as travelling or sociality, and “intense perception and observation by on-site inspection of architecture.” 11 Margitta Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move”, in Lara Schrijver, ed., The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021), 83-96 (p. 89). Hulusi Güngör’s book entitled How to Build Cities (1969), which he compiled by using his own photographs from multiple trips in Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland (Figure 2) displays the practice of building a repertoire in action. The systematic delivery of his photographs under themes such as parks, marketplaces, stalls, and more, not only displays his approach to rapidly disseminate architectural knowledge, but it also shows the reflexivity of architects to collect and archive, in order to concretize those sources at a convenient time. 12 Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move”, 90.

Travel as Network and Legacy

Oral presentations and lectures seem to have a lasting effect on architects’ interests and reasons to mobilize. Most of the architects recall a presentation or a lecture they listened to, either as a student or a staff member in the university. Especially modernist architecture had resonated with young architects through various representations. For instance, Burhan Arif Ongun, who went to Paris to work with Le Corbusier in 1928-1930, mentions that he became acquainted with LC and Towards a New Architecture through Celal Esad Arseven’s lectures. 13 Uğur Tanyeli, Mimarlığın Aktörleri 1900-2000 (İstanbul: Garanti Galeri, 2007), 66-67. Arseven taught influential architectural history courses at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University (MSFAU) and was the author of Yeni Mimari [New Architecture] (1931) –the first written contribution to modernist architecture in Turkish language.

Figure 3 Pages from Orhan Şahinler’s A Study on Medieval City Squares and Neighborhoods in Central Italy (1964)

Ersen Gürsel was similarly influenced by Muammer Onat’s lectures on central Italy, became “obsessed with seeing all the European cities his tutors had mentioned” and applied for a research trip scholarship in Spain in 1967. 14 Ersen Gürsel, Interview with author, 05 June 2020. Onat had visited a friend who lived in a social housing estate on the outskirts of Rome in 1960, was intrigued by INA-CASA and spent his entire trip to research on it. He actually compiled a book draft based on his experiences -although he never published, he gave lectures about the subject. There was a recurring theme of Mediterranean architecture through trips to Italy in MSFAU: Orhan Şahinler also went to Italy in 1955 and 1962, and published a research and sketch book entitled A Study on Medieval City Squares and Neighbourhoods in Central Italy (1964) (Figure 3). He was followed by Muzaffer Sudalı and Olcay Ünlüsayın, who published a book 15 Muzaffer Sudalı, INACASA İş ve Konut Bir toplumsal dayanışma [INACASA Work and Housing A Societal Solidarity] (Istanbul: ITU, 1967). and an article 16 Olcay Ünlüsayın, “INA-CASA ve Toplu Sosyal Konut Üzerine [INA-CASA and on Mass Social Housing]”, Mimarlık, 156 (1978), 15-16. on INA-CASA, respectively. These architects consulted each other’s research and visited Italy to contribute to the discourse around post-war social housing. These examples collectively show that, the way in which architects mobilized themselves, as well as knowledge, is always strongly tied to architectural actors, oral trajectories and representations they encounter, and the networks through which they share tacit knowledges.

Figure 4 Turgut Cansever’s sketches showing the environment while on the road in Scandinavia, 1950. With Emine Cansever Öğün’s permission.

For instance, Enis Kortan recalls the 1953 special issue of L’architecture d’aujourd’hui magazine on architects who contributed to modernist architecture in the U.S.A and he immediately decides to visit and “inspect on” these Bauhaus school architects’ works “on the spot”.

17

Enis Kortan, Towards a Humanist Architecture (Istanbul: Boyut, 2012), 38.

Similarly, Turgut Cansever “was wondering about how the buildings that he knew from the magazines were doing” and went on a long trip around Europe.

18

Uğur Tanyeli and Atilla Yücel, Turgut Cansever: Düşünce Adamı ve Mimari [Turgut Cansever: A Man of Thought and Architect] (Istanbul: Garanti Galeri, 2017), 122,124.

After his return, Cansever, who is known for his elaborate attention to architectural details and materials, was asked to teach about what he had seen and he particularly elaborated on Scandinavian architecture.

19

Tanyeli and Yücel, Turgut Cansever, 124.

His sketches of the natural and built landscape on the road through Denmark and Norway reflect the atmosphere of his trip through their positions, details and scales in the notebook (Figure 4).. There were probably other students who attended his aforementioned lectures and found themselves wanting to visit Scandinavia.

Similarly, Turkish architectural historian Doğan Kuban was deeply influenced by his mentor Paolo Verzone. As Verzone’s student, Kuban went on a research trip to Italy in 1954 and wrote his theses on Turkish and Italian architecture.

20

‘An Evaluation of Ottoman Baroque Architecture’, (unpublished doctoral thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 1954) and ‘The Formation of Interior Space in Ottoman Religious Architecture – A Comparison with Renaissance’ (unpublished docent thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 1958), respectively.

Kuban emphasized the importance of comparison as a way of interpretation and saw writing, traveling (especially in Europe), teaching and architectural translation as integral elements for his self-building. Yıldız Sey remembers attending many trips with Kuban and later trying to pursue this tradition themselves.

21

Bülend Tuna, Mimarlar Odasından Portreler: Yıldız Sey (Istanbul: TMMOB, 2021), 45.

Sey mentioned the frequency of trips to destinations they “needed to see and learn about” and through them, “would get to know Turkey and learn together with friends”.

22

Tuna, Mimarlar Odasından Portreler, 43-45.

Especially trips to Anatolia had an underlying motivation of “getting to know the country.”

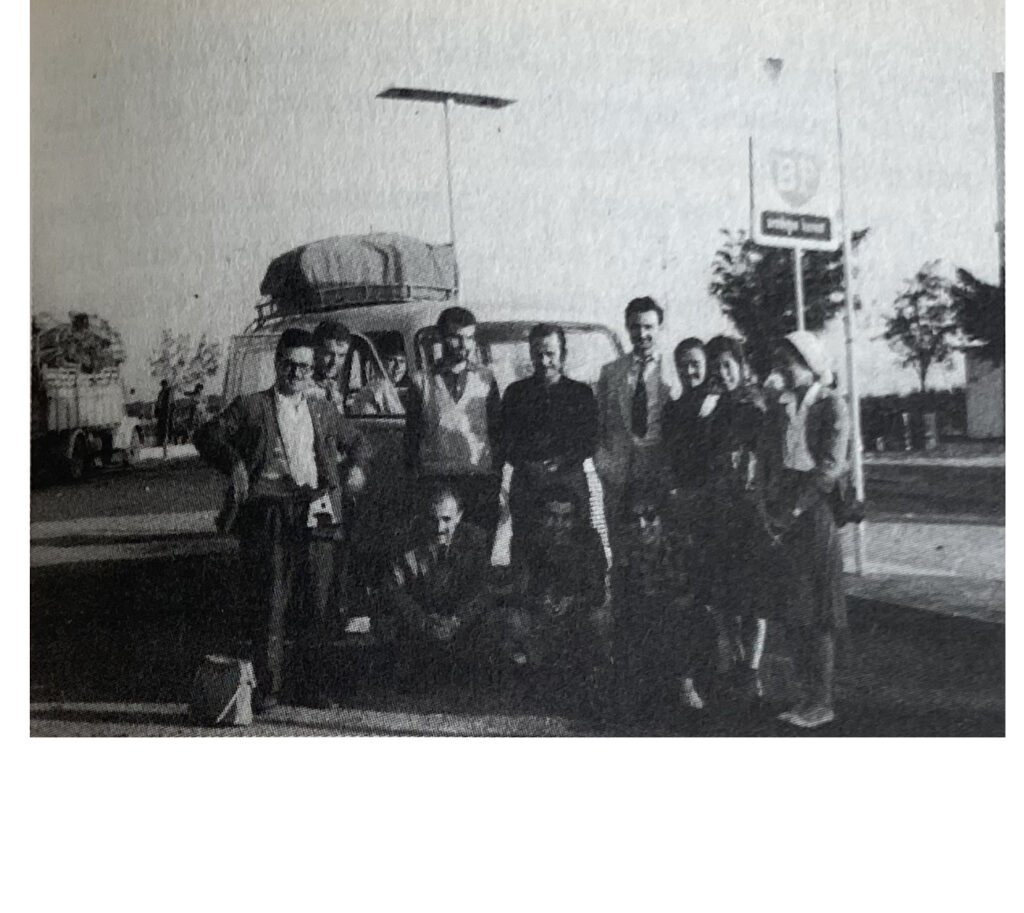

Figure 5 Doğan Kuban on a trip from Istanbul to Diyarbakır with his students

Kuban was a key figure in maintaining such trips throughout the 1960s and carried out the legacy of traveling throughout his academic life and organized many faculty-funded trips to Anatolia

23

Tr. Anadolu Gezilerinden İzlenimler: Bir Batı Anadolu Gezisi. Despite the difficulties of transportation and accommodation in 1960s’ Turkey, Kuban comments on the positive, exciting and bonding effects of these trips, as well as their roots for his love for Anatolia.

with his students (Figure 5), which resourced one of his books entitled Impressions from Anatolian Trips: A Western Anatolian Trip (1962). In the foreword of the book, Kuban frames culture as an entity that can only be understood in its environment and that architecture students find the opportunity to acquire realistic knowledge necessary for their formation through architectural trips.

24

Doğan Kuban, Anadolu Gezilerinden İzlenimler: Bir Batı Anadolu Gezisi (Istanbul: Istanbul Technical University Press, 1962).

His idea not only designates culture as a spatial phenomenon, but it also attributes a necessity to travel. Kuban seems to emphasize the kind of experience that is gained on site, incorporating all five senses and therefore is embodied, and planned out based on one’s personal knowledge and interests -which are the characteristics of the kind of experience that contributes to personal knowledge in Polanyi’s approach. These school trips contributed to the internalization of explicit knowledge such as architectural history, through experience.

Kuban deeply valued such trips and believed that collecting documents for future studies and archives is the major acquisition to be gained from them.

25

Doğan Kuban, A Renaissance Man, interview by Müjgan Yıldırım (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Yayınları, 2007), 146-148.

Kemal Ahmet Aru’s approach to traveling aligns with Kuban’s and reflects the reflexivity that some architects shared:

“in 1965, I was delegated to inspect in the USA and stayed there for three months. To see the education in the universities, collect material and attend some of the academics’ courses and juries there…one should collect all the information and deliver it to the right place. To filter, bring out and disseminate – this was my concern. I went around the whole world and collected various documents everywhere I went.”

26

Kemal Ahmet Aru et al., Anılarda Mimarlık, 23.

The tendency to collect through recording (such as photographs, drawings and other ephemera) and disseminate is perhaps particular to the architecture discipline, partly because architects converted travel media into an “inseparable part of their own existence as myths and icons.” 27 Rubén A. Alcolea and Jorge Tarrago, “Spectra: Architecture in Transit” in Craig Buckley and Pollyanna Rhee, ed., Architects’ Journeys:Building, Traveling, Thinking (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2011), 6-19, (9). In other words, the dissemination of their travel experiences help to construct architects’ own professional identities. Historian Sidney K. Robinson asserted that, despite architects collect travel images that are not much different than those by tourists, they can be impending because they might reappear in the form design. 28 Sidney K. Robinson, “Architects as Tourists”, Journal of Architectural Education, 3 (1980), 27-29. In fact, the aforementioned architects all expressed that their trips were defining moments and influential on their design and teaching careers.

Conclusion

The skill and experiences gained through traveling, coincides with what Michael Polanyi calls the ‘intelligent effort’: after receiving an education based on theoretical principles, architects strengthened their skill sets through observation and recording during their travels, and producing after their travels.

This variety of visual, verbal and written material, as well as the ways in which they disseminate through architects, institutions and publications, necessitates an understanding of architectural discourses through networks and relationships.

29

Helene Roth et al., Arrival Cities: Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020), 13.

As travel triggers productions, either in verbal or written form, the dissemination of ideas creates and sustains flux in architecture culture. An architect’s knowledge expands and changes as architects travel and reflect on and translate their traveling experience.

Traveling, along with other forms of embodied knowledge in architecture, incorporated experience and observation, which are both strongly tied to the individual’s own perception, and therefore, personal history and knowledge. In fact, Turkish architects’ travels demonstrate the practice of translation from experience to representation, or from tacit to explicit knowledge. Each trip, along with its associated experiences, actors and related network, draws a frame of the traveling architect’s way of “knowing”.

- Joan Ockman, “Bestride the World Like a Colossus: The Architect as Tourist” in Joan Ockman and Salomon Frausto, ed., Architourism: Authentic, Escapist, Exotic, Spectacular” (Munich: Prestel, 2005), pp. 158-185 (p. 161).

- Emine Seda Kayım, “1920-1960: İstanbul – Stuttgart Hattı Kemali Söylemezoğlu’nun Kariyeri Üzerinden Türk-Alman Mimarlık İlişkilerini Okumak”, Unpublished Phd thesis (Istanbul: Yıldız Technical University, 2010).

- Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (New York: Harper & Row, 1964), 63-64.

- Seyfettin Nasıh, “Stadyumlar: Almanya Stadyumları Hakkında Bir Tetkin Raporu [Stadiums: A Study Report on German Stadiums]”, Arkitekt, 33-34 (1933), 299-314.

- Sibel Bozdoğan, Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 75.

- Şevki Balmumcu, “Küçük Seyahat”, Arkitekt 3, 39 (1934), 92-95.

- Jilly Traganou, “For a Theory of Travel in Architectural Studies”, in Jilly Traganou and Miodrag Mitrasinovic, ed., Travel, Space, Architecture(Surrey: Ashgate, 2009), 4-26 (p. 5).

- Winfried Löschburg, Seyahatin Kültür Tarihi [Kleine Kulturgeschichte des Reisens], translated by Jasmin Traub (Ankara: Dost Kitabevi Yayınları, 1998), 7-9.

- Caren Kaplan, Questions of Travel: Postmodern Discourses of Displacement (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 23-25.

- Julie Willis, “Architectural Movements: Journeys of an Intercolonial Profession”, Fabrication 26, 2 (2016), 158-179 (p. 158).

- Margitta Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move”, in Lara Schrijver, ed., The Tacit Dimension: Architecture Knowledge and Scientific Research (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2021), 83-96 (p. 89).

- Buchert, “Design Knowledges on the Move”, 90.

- Uğur Tanyeli, Mimarlığın Aktörleri 1900-2000 (İstanbul: Garanti Galeri, 2007), 66-67.

- Ersen Gürsel, Interview with author, 05 June 2020.

- Muzaffer Sudalı, INACASA İş ve Konut Bir toplumsal dayanışma [INACASA Work and Housing A Societal Solidarity] (Istanbul: ITU, 1967).

- Olcay Ünlüsayın, “INA-CASA ve Toplu Sosyal Konut Üzerine [INA-CASA and on Mass Social Housing]”, Mimarlık, 156 (1978), 15-16.

- Enis Kortan, Towards a Humanist Architecture (Istanbul: Boyut, 2012), 38.

- Uğur Tanyeli and Atilla Yücel, Turgut Cansever: Düşünce Adamı ve Mimari [Turgut Cansever: A Man of Thought and Architect] (Istanbul: Garanti Galeri, 2017), 122,124.

- Tanyeli and Yücel, Turgut Cansever, 124.

- ‘An Evaluation of Ottoman Baroque Architecture’, (unpublished doctoral thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 1954) and ‘The Formation of Interior Space in Ottoman Religious Architecture – A Comparison with Renaissance’ (unpublished docent thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 1958), respectively.

- Bülend Tuna, Mimarlar Odasından Portreler: Yıldız Sey (Istanbul: TMMOB, 2021), 45.

- Tuna, Mimarlar Odasından Portreler, 43-45.

- Tr. Anadolu Gezilerinden İzlenimler: Bir Batı Anadolu Gezisi. Despite the difficulties of transportation and accommodation in 1960s’ Turkey, Kuban comments on the positive, exciting and bonding effects of these trips, as well as their roots for his love for Anatolia.

- Doğan Kuban, Anadolu Gezilerinden İzlenimler: Bir Batı Anadolu Gezisi (Istanbul: Istanbul Technical University Press, 1962).

- Doğan Kuban, A Renaissance Man, interview by Müjgan Yıldırım (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Yayınları, 2007), 146-148.

- Kemal Ahmet Aru et al., Anılarda Mimarlık, 23.

- Rubén A. Alcolea and Jorge Tarrago, “Spectra: Architecture in Transit” in Craig Buckley and Pollyanna Rhee, ed., Architects’ Journeys:Building, Traveling, Thinking (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2011), 6-19, (9).

- Sidney K. Robinson, “Architects as Tourists”, Journal of Architectural Education, 3 (1980), 27-29.

- Helene Roth et al., Arrival Cities: Migrating Artists and New Metropolitan Topographies in the 20th Century (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2020), 13.