Return to archive

title

From Unconventional Households to Unconventional Affordable Housing

authors

Gennaro Postiglione Paola Briata Constanze Wolfgring

Abstract

Over the past years, a multi-disciplinary group of scholars at Politecnico di Milano (UHUAH!) has been exploring how contemporary social and demographic dynamics challenge housing policies and projects. These issues have been at the core of teaching activities in design-based studios involving architecture students. Spurred on not only by the literature on the subject (Ronald/Elsinga, 2012), we are engaged in field research investigating the state of the art of dwelling practices, with the aim to develop alternative housing solutions (and typologies) able to overcome the distance that emerged between demand and supply. A gap mostly depending on the major changes that happened in the last twenty years in households composition, and in what is typically referred to as the family (Carlson/Meyer, 2014), with the consequent crisis of the ideal equivalence between “the family” and the “apartment typology” (Star strategies + architecture, 2016). The paper will therefore present relevant case studies from the Research by Design explorations conducted on existing building stock, a decision taken to empower Adaptive Reuse as a sustainable approach also in Housing. Our Design Manifesto considers the apartment as constituted by a system of independent rooms, in which the bed is not anymore the core device, while the connective space is interpreted as common shared areas (Connective = Collective).

Prologue

Over the past years, a multi-disciplinary group of scholars at Politecnico di Milano (UHUAH!) has been exploring how contemporary social, demographic, and economic dynamics challenge housing policies and projects. This question has been at the core of (1) teaching activities in architectural design studios and (2) field research investigating the state of the art of dwelling practices related to unconventional housing solutions (and typologies) able to overcome an increasing distance between demand and supply. This gap mostly results from major changes that have happened in the last twenty years regarding the composition of households and the conventional understanding of the nuclear family (Carlson/Meyer, 2014; Borasi 2022). Consequently, a crisis of the ideal equivalence between “the family” and a corresponding apartment typology, as promoted by the Modern Movement, can be recognized (Star strategies + architecture, 2016).

Moreover, changing economic and employment conditions have reduced housing affordability and increased precarious housing conditions (Costa et al., 2014), fostered multilocal living, and the emergence of new lifestyles (Rolshoven, 2017).

Starting from these societal transformations, this essay presents a research and teaching experience aimed at investigating ‘unconventional’ housing practices and projects, hence, understanding how individuals, households, and professionals (e.g., architects, planners) respond to these developments in the organization and design of housing solutions, and at exploring the potential of such solutions to promote housing affordability at the individual and urban scale.

Sustainable cities require affordable housing

The theoretical framework supporting our reflection draws from two streams of literature connecting the right to housing to the right to the city, as well as the right to housing to a design perspective “beyond growth-dependence” (Rydin, 2012).

The first stream has underlined how, in contemporary cities, the right to housing is more and more a specific and fundamental side of the right to the city. A home is first of all intended as a place where people can express physical domain (a decent place for dwelling), social domain (a place where both privacy and right to sociality are guaranteed), and legal domain (a certain degree of tenure security and legal protection against eviction) (Tosi, 2017). In many cities, not having a home is the main marker to determine who is in a serious condition of poverty and exclusion, and who is not (Blanco, León, 2016; Watt, Minton, 2016; Minton, 2017; Colini, 2019). Discussing how architecture can contribute to sustainable cities and communities therefore has to revolve around the question of what architects can do to increase affordable, accessible and adequate housing—not only in a logic of justice (the right to the city and the right to housing), but also regarding the sustainability of the concept of the city itself: throughout its history, the urban promise—the city as a market of life opportunities (Siebel, 2015) and a “machine of inclusion” (Benze/Rummel, 2020)—has attracted people to the cities, turning them into what they are in their most positive connotations: sites of growth, attraction, creativity, entrepreneurship, potential. The success of an urban agglomeration has directly been linked to the physical presence of its dwellers. Until the neoliberal turn, those who worked in a city, who kept its basic systems going, had good reason to believe that they were able to afford a home in the very city to whose liveability they contribute. More and more, however, this doesn’t add up. A global housing affordability crisis is unfolding, affecting particularly growing and attractive cities (Wetzstein, 2017). A prototypical example of this is the city of Milan: with average rents that have increased by over 32% between 2015 and 2020 to an average of 20,3€/m² in September 2020 (immobiliare.it, 2022), while average wages have increased by only 7,8% within this period (Corriere della Sera, 2020), housing unaffordability is no more ‘just’ a problem of socioeconomically marginal groups, but increasingly affects broad sections of the societal spectrum.

The second stream of literature is helpful to frame the types of contexts and buildings considered in our work. This is related to strategies that may be carried out in contemporary capitalist and neoliberal cities to have “prosperity without growth” (Jackson, 2011). These perspectives are interesting because they look quite far from radical thinking about “de-growth” (Latouche, 2007), but show how growth-dependence could create serious social, ecological and economic problems in the context of the capitalist city.

In this direction, Rydin (2012) has argued about resources and principles to promote planning, and urban and housing policies beyond growth dependence. Among the principles she suggests there is a broad idea of “resource” that does not only include economic assets but also, for example, the value of existing spatial and social practices that might be supported through design. At the same time, this is a perspective encouraging the reuse and recycling of existing buildings and facilities instead of building new ones.

Learning from practices, projects, and design

The adopted methodology combined the analysis of case studies, architectural ethnography (direct participant observation, interviews, photography, drawing, writing, etc.), and a research-by-design approach, applied within architectural design studios. Over a period of six years, BA and MSc architecture students have conducted design explorations on the Milanese existing (residential and non-residential) building stock—employing a logic of adaptive reuse as a sustainable approach in housing—with the task to develop unconventional affordable housing solutions. The research strives to contribute to the advancement of knowledge on the link between unconventional housing solutions and affordability in different ways: a) in conceptual terms, by attempting a systematic analysis and classification of the case studies collected in the past years—distinguishing between unconventional housing practices, housing solutions that are often bottom-up or third-sector driven targeting particular (often precarious) population groups, and unconventional housing projects, experimenting new ways of dwelling, often with an articulated architectonic design programme; b) in architectural terms, by discussing how architecture and design choices can promote the affordability of housing – through its layout (e.g. the minimization of private spaces in favour of shared spaces), the choice of materiality, the implementation of design elements allowing for flexibility and adaptability to changing household and life situations, self-build/renovation.

Diagrams and descriptions of household profiles have been mapped and grouped by typologies of users and compiled into an Atlas to reduce the reality’s complexity and to allow for the initiation of a design process with a different conceptual framework (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

1) Diagrams and descriptions of household profiles have been mapped and grouped by typologies of users and compiled into an Atlas to reduce the reality’s complexity and to allow for the initiation of a design process with a different conceptual framework (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

The fieldwork aimed at mapping different housing practices illustrating in which ways social transformations at the local and global scales directly impact on people’s lives, who seek solutions to their housing needs according to their specific socio-economic circumstances. For instance, the structural economic crisis of the last decade has led to a considerable increase in the number of households in which adult children (alone/as couples, with or without children) return to live with their parents, thus rebuilding extended families, typical of pre-industrial societies. In elderly households, we often noticed the presence of a live-in caregiver, a practice to avoid the recourse to more expensive institutional solutions. We moreover encountered cases in which the original family unit, consisting of a traditional nuclear family or a single parent, opens up to accommodate others with whom no family relationships exist; a process that we might define as “mutual aid or benefit”. Households offering a room and some space to share in their home, on a permanent or temporary basis (the latter has become increasingly common over the last few years), are often driven to do so by the need to supplement their monthly income. Similarly, households that manifest the need for co-living arrangements are often—though not exclusively—unable to access market housing (for example individuals with stable employment whose income does not allow them to afford market housing). Another significant group consists of individuals renting rooms in shared apartments, arising from the need to live in two or more places for work reasons; for this group, home-sharing is a comfortable and affordable solution. The results of our broad investigations of instances around the globe show the increasing popularity of home-sharing, even for older generations—particularly in large metropolises where housing is becoming less and less affordable.

Work sheet showing the main quantitative and qualitative information collected during the survey period (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

2) Work sheet showing the main quantitative and qualitative information collected during the survey period (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Following the production of the Atlas, each case study has been further investigated by the students individually through interviews with household members, a diary of domestic life, and collecting information about the behaviour, problems, and wishes of the occupants with regard to the organization and use of space. The information was diagrammed and daily household routines were cross-analysed regarding the shape of the space, the layout of furniture, and the general typology of the dwelling, distinguishing between private and collective spaces and their degrees of crowding.

Redrawing, by hand, the space—with its equipment—occupied by the investigated households (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

3) Redrawing, by hand, the space—with its equipment—occupied by the investigated households (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

The students were asked to re-draw the dwelling in plan and section, paying particular attention to the representation not only of the architectural structure but also of pieces of furniture or accessories that describe how people occupy and live in the spaces. Although there have been countless studies with multidisciplinary approaches, ranging from social over political to behavioural analyses, few scholars have so far studied the specifically spatial and architectural aspects—down to the level of furnishing details—of house-sharing conditions and practices. Adopting an ethnographic approach and making use of its manifold tools can contribute to gaining an understanding of the unique architectural and furnishing characteristics of dwellings and their uses, in order to describe their limits, needs, and potentials.

Drawing focusing on the life around furniture (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

4) Drawing focusing on the life around furniture (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Special attention was dedicated to the observation and the representation of different usages and rituals activated and/or supported by furniture. The drawings display how some furnishings were able to respond to the needs of the users, allowing uses that are different from those for which they were designed. Thereby emerged a catalogue of affordances (Gibson, 1966) of tables, carpets, beds, and their transformation into objects for the most diverse activities. Such affordances are potentially present in every artifact, but they find expression only where the user is able to activate them.

The collective house by Teige (1932) vs. the plan-efficiency scheme by Klein (1929) (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

5) The collective house by Teige (1932) vs. the plan-efficiency scheme by Klein (1929) (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Teige’s diagrams revisited by our research cluster (@ReCoDe-DAStU), expanding the inhabitant’s private space beyond the bedroom, proposing to include spaces for childcare and hygiene, and imagining a different interpretation of the bedroom.

6) Teige’s diagrams revisited by our research cluster (@ReCoDe-DAStU), expanding the inhabitant’s private space beyond the bedroom, proposing to include spaces for childcare and hygiene, and imagining a different interpretation of the bedroom.

Teige, Hilberseimer and Ginzburg proposed an alternative spatial and political vision to Klein’s diagram for an Existenzminimum. For Teige, the collective house is based on shared spaces, collective living, and public facilities, where individual privacy is limited only to the personal room (the cell), while Klein’s proposal is based on individualism, privacy, and miniaturization. Living at home is privatized within the flat walls and proportioned, according to the Existenzminimum, on the number of beds (equal to that of people) inhabiting the flat. This scheme has been the starting point for the development of national housing standards, and the editing of Neufert’s design manual. On the opposite, Teige’s ideas did not reach beyond the Soviet Union. Recently, thanks to research conducted by Aureli and Tattara (DOGMA), the politics, poetics and history of sharing in architecture have been rediscovered and became objects of theoretical and design explorations (DOGMA, 2017; 2019; Coricelli 2020).

The New Words of Housing [Design]: A Tentative Manifesto (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

The collected data constituted the basis for reflecting on spatial and distributional particularities to be considered when designing for shared housing, resulting in guidelines and recommendations for designing a housing typology for shared living—the five-point Tentative Manifesto.

The main core and innovative elements of the Manifesto are: a) the marginalization of the bed within the private room; b) the transformation of the Connective space into Collective areas; c) the updating of the idea of the flat into a constellation of rooms.

Diagram for the Unit and its possible spatial interpretations (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

8) Diagram for the Unit and its possible spatial interpretations (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

As presented in the Manifesto, the Unit is a space open to hosting a single or a couple Nucleus; for every further person who might belong to the same Nucleus, one simple room is added. From a perspective of design interventions on the existing building stock, the strategy is to implement the project by using three-dimensional (walk-in cabinet), bi-dimensional (wardrobes and bookshelves), mono-dimensional (sliding/foldable panels), and zero-dimensional (doors, windows, curtains) devices.

Diagram for the Conn/ll-ective space and its possible spatial interpretations (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

9) Diagram for the Conn/ll-ective space and its possible spatial interpretations (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

As presented in the Manifesto, the Conn/ll-ective space is a continuous area among Units and Clusters. It is constituted by a multitude of corners, flowing along the Aggregation, connecting different service areas equipped with kitchen/s, tables and/or sofas, etc.

The continuous conn/ll-ective space is consistently arranged into distinct areas of different shapes and sizes to accommodate different occupants at the same time, avoiding tensions or conflicts due to their appropriation and/or occupation. Particular attention is given to spatial solutions for the elderly, aimed at minimizing feelings of loneliness and isolation for those living alone. Private spaces are characterised by greater vitality, creating areas for social interactivity to which only members of the cluster have access, thus ensuring a balance between moments of conviviality and sharing and more private, intimate moments.

10–19) Reloading Grattacielo Baselli (P. Portaluppi, 1952, Milan) – (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

To carry out the design exercise, residential and non-residential buildings in Milan were chosen from a wide range of twentieth-century examples. The projects reveal with immediacy the differences in organization and layout of interior space, testifying to the complexity of housing needs and the vitality of new configurations, as well as the attempt to articulate public, private, and collective spaces in new ways.

External views of Grattacielo Baselli.

10) External views of Grattacielo Baselli.

Grattacielo Baselli footprint (main structure and external walls).

11) Grattacielo Baselli footprint (main structure and external walls).

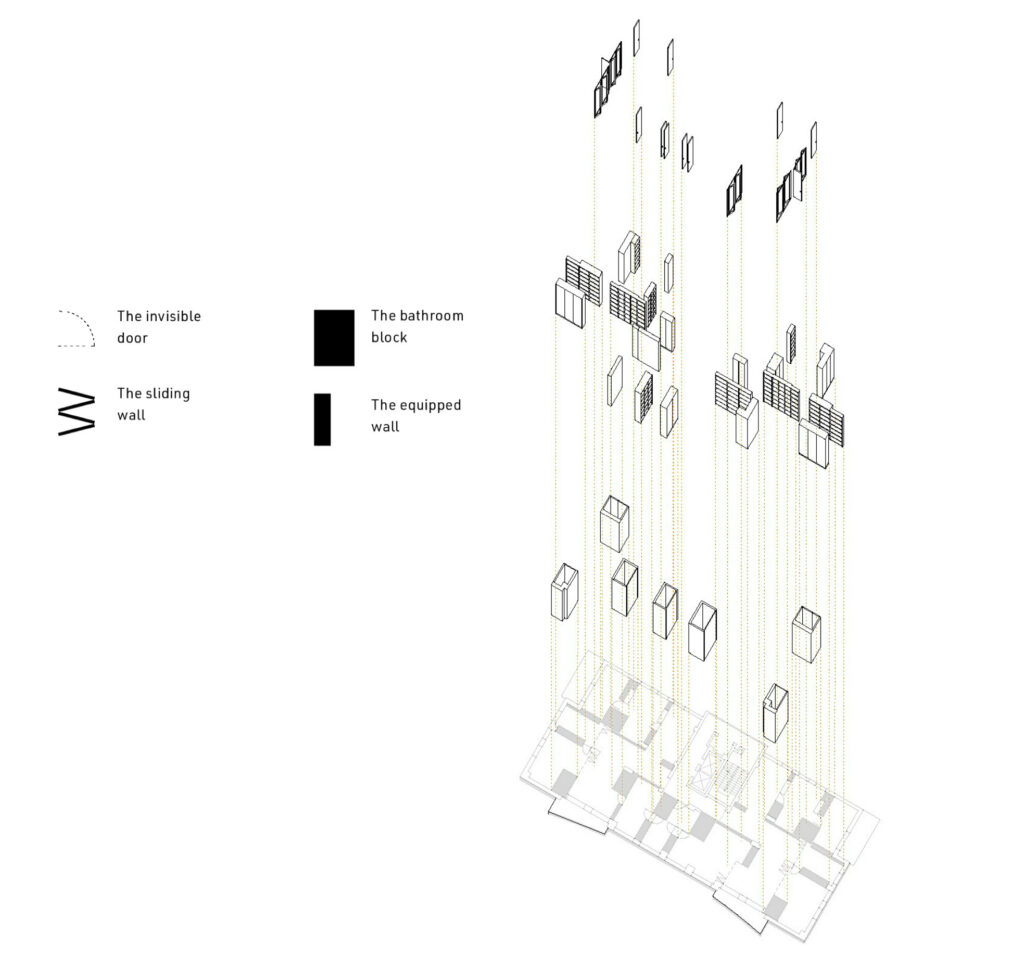

Design strategy: a set of devices is set in place in dialogue with the existing structure (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

12–13) Design strategy: a set of devices is set in place in dialogue with the existing structure (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

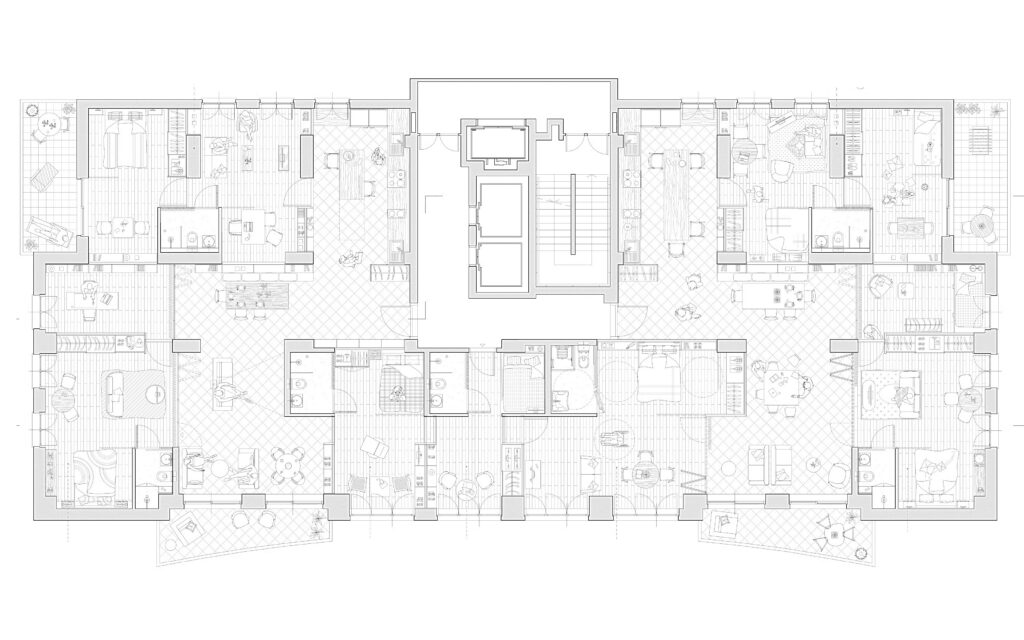

Design proposal: a possible floor plan for Grattacielo Baselli highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

14–15) Design proposal: a possible floor plan for Grattacielo Baselli highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: detail of a Cluster for elderly with a caregiver (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

16) Design proposal: detail of a Cluster for elderly with a caregiver (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Special attention is paid to the interaction between the social space of the Cluster and that of the Aggregation. Foldable doors and curtains are set in place allowing for permeability between the two areas, expanding the space for the elderly towards the “interior shared space” as an inner square on which to interact during the day.

Design proposal: different solutions of Units equipped according to the users’ profile: the room has a quality that goes beyond its functionality, and it is open to a plurality of usages. This is what we have defined as Typological Affordances or spatial resilience (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

17) Design proposal: different solutions of Units equipped according to the users’ profile: the room has a quality that goes beyond its functionality, and it is open to a plurality of usages. This is what we have defined as Typological Affordances or spatial resilience (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: possible interior elevation with a focus on materiality (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

18) Design proposal: possible interior elevation with a focus on materiality (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: different layout according to how rooms are bound together (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

19) Design proposal: different layout according to how rooms are bound together (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

The presence of a second or third door allows for an easy re-arrangement of the Aggregation layout. Circularity in the accessibility of spaces guarantees a high degree of flexibility without any transformation of the space.

20–23) Reloading La Viridiana (L. Caccia-Dominioni, V. Magistretti, 1969 Milan) – (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Other investigations by design have been conducted on La Veridiana, a Milanese masterpiece from the 1960s. The singularity of the design lies in the proposal for putting in place a unique system device able to accommodate the space for Units and Clusters as well as for articulating the Conn/ll-ective space, reducing the intervention to a minimum footprint.

External view of one of the La Viridiana blocks (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

20) External view of one of the La Viridiana blocks (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

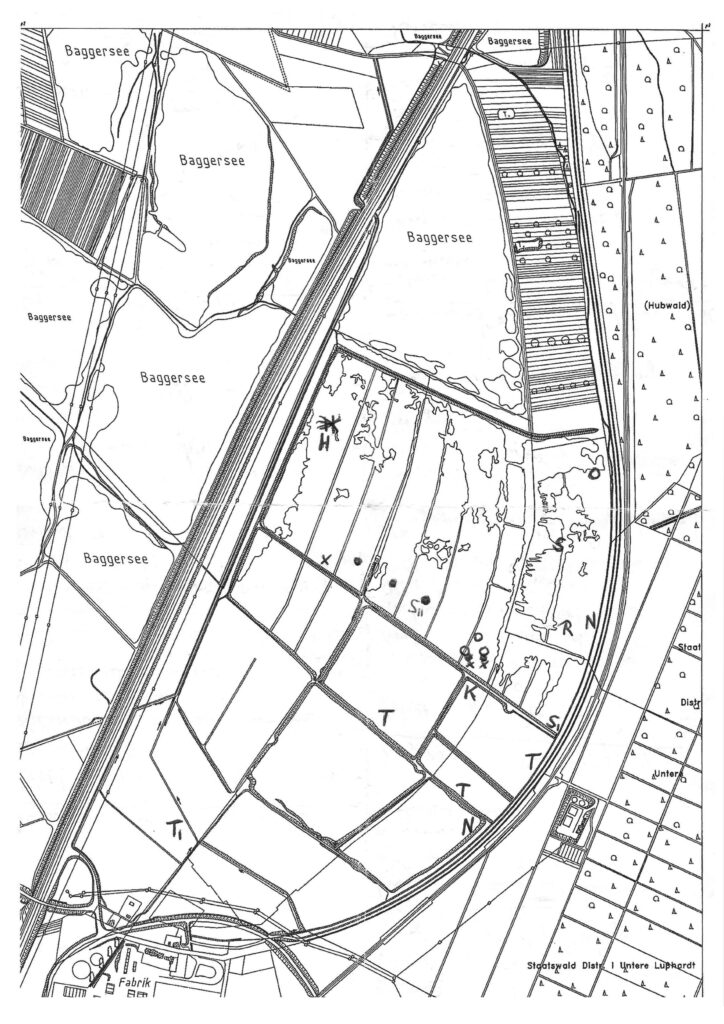

La Viridiana footprint (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

21) La Viridiana footprint (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design strategy: a set of devices is set in place in dialogue with the existing structure (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

22) Design strategy: a set of devices is set in place in dialogue with the existing structure (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: a possible floor plan for La Viridiana highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

23) Design proposal: a possible floor plan for La Viridiana highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

24–28) Reloading San Siro (INA casa Office, 1937 Milan) – (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

External view of the San Siro neighbourhood (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

24) External view of the San Siro neighbourhood (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

San Siro footprint (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

25) San Siro footprint (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: a possible floor plan for San Siro highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

26) Design proposal: a possible floor plan for San Siro highlighting the different devices set in place (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Design proposal: possible usages of the space according to the inhabitants’ profiles (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

27) Design proposal: possible usages of the space according to the inhabitants’ profiles (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

Exhibition “ReCoDe – Reloading Contemporary Dwelling”, Politecnico di Milano, 2016 (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

28–29) Exhibition “ReCoDe – Reloading Contemporary Dwelling”, Politecnico di Milano, 2016 (@ReCoDe-DAStU).

References

- Benze A, Rummel D (2021) Inklusionsmaschine STADT. JOVIS, Berlin/Boston

- Blanco I, León M (2017) Social innovation, reciprocity and contentious politics: Facing the socio-urban crisis in Ciutat Meridiana, Barcelona. Urban Studies 54(9):2172–2188.

- Borasi G (2022) A Section of Now. CCA Spector Books, Berlin

- Carlson M, Meyer D (2014) Family Complexity: Setting the Context. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 654(1):6–11

- Coricelli F. (2020), New Domestic Rentalscape. A critical insight into middle-class housing, Dissertation, Politecnico di Torino.

- Corriere della Sera (2020) Lavoro a Milano, la classifica degli stipendi. https://milano.corriere.it/notizie/economia/22_giugno_01/lavoro-milano-classifica-stipendi-85dd1f50-e171-11ec-bb0d-bf3a1b8d46c7.shtml Accessed 05 October 2022

- Costa G, Bezovan G, Palvarini P, Brandsen T (2014) Urban Housing Systems in Times of Crisis. In: Ranci C et al. (eds.) Social Vulnerability in European Cities, Palgrave Macmillan, London, p 160-186

- Dogma (2017), The Room of One’s Own, Black Square, Milano.

- Dogma (2019) Loveless. The Minimum Dwelling and its Discontents, Black Square, Milano 2019.

- Gibson J (1966) The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. Allen & Unwin, London

- Immobiliare.it (2022) Quotazioni immobiliari nel comune di Milano. https://www.immobiliare.it/mercato-immobiliare/lombardia/milano/ Accessed 05 October 2022

- Jackson T (2011) Prosperity without growth: Economics for a finite planet. Earthscan, Abingdon/New York

- Latouche S (2007) La scommessa della decrescita. Feltrinelli, Milan

- Minton A (2017) Big Capital. Who is London for? Penguin, London

- Ronald R, Elsinga M (2012) Beyond Homeownership: Housing, Welfare and Society. Routledge, London

- Rolshoven J (2007) The Temptations of the Provisional. Multi-Locality as a Way of Life. Ethnologia Europaea 37(1-2):17-25

- Rydin Y (2012) Governing for Sustainable Urban Development. Earthscan, Abingdon/New York

- Siebel W (2015) Die Kultur der Stadt. Suhrkamp, Berlin

- Star strategies + architecture (2016) The Interior of the Metropolis. Domestic Urbanism. MONU 24:106-113

- Tosi A (2017) Le case dei poveri. Mimesis, Sesto San Giovanni

- Watt P, Minton A (2016) London’s Housing Crisis and its Activisms. City vol. 20(2):204-221

- Wetzstein S (2017) The global urban housing affordability crisis. Urban Studies 54(14): 3159–3177