Return to archive

title

A Post-Post Positional Praxis: Locating ideas of repair in a Southern city

Author

Jhono Bennett

Abstract

Abstract The legally implemented South African Apartheid city model of the 20th Century very specifically separated urban inhabitants along strict racial spatial definitions as set out by city practitioners and mandated by the national government on top of the existing colonial state model of segregation. These societal logics and legal systems have had a wide-scale systemic phyco-spatial effect on the many generations of urban dwellers who have no reference to patterns of living and space-making outside of this city-model. More specifically, the laws and regulations that carried these ideologies have instilled largely prejudiced tacit forms of understanding of self and ‘other’ that remain deeply entrenched in the spatial practitioners who are trusted to design and make within this context. For this reason, a critically proactive engagement with these harmfully biased tacit knowledge systems is a crucial endeavour across the built-environment practice – especially so in the architectural and the related spatial design disciplines. Such a deeply interpersonal recognition of such dynamics within spatial-design practice call for approaches, methods, and techniques that operate through considered and inclusive forms of practice that are often difficult to frame within the current ‘northern’ framings of the architect or the designer. Instead, other conceptual frameworks such as Southern Urbanism offer a more situated armature to locate these questions and begin an other-wisely based inquiry through these challenges. By thinking about an architectural - or more appropriately: a spatial design practice - through values and actions that are true to the locus of the site from which they exist, on the situated terms of the context that produce them, and through the languages – spoken, gestured and visual – that they are actioned through; the research holds an the potential to reveal other forms of more connective tacit knowledge that exist in these ways of making and maintaining urban spaces. Such an inquiry holds the potential to guide these practices both within the disciplines of the architect and support those engaging with these dynamics to expand their understandings of practice and the ‘Imaginative Geographies’ of separation and difference that continue to shape the post-Apartheid and post-Colonial cities of South Africa.

Locating a Tacit Collective Socio-Spatial Bias

A Tacitly Biased Socio-Spatial System

The twentieth-century South African Apartheid city model very specifically separated people socio-spatially along legally-justified racial categories, 1 Alan Mabin and Dan Smit, “Reconstructing South Africa’s Cities? The Making of Urban Planning 1900–2000,” Planning Perspectives 12, no. 2 (1997): 193–223; Leonard Thompson and Lynn Berat, A History of South Africa (Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2014). 56 -125 confining grossly unjust spatial access to the country’s resources to a White South African minority ruling class. Underpinned by the social ideologies of ‘separateness’ under the Apartheid state, these actions were implemented by practitioners through very explicit built infrastructures, overseen by officials at a city scale, and mandated by the national government policy frameworks that effectively continued the systems set in place by the preceding centuries of colonial control. These tacitly embedded socio-spatial logics have greatly contributed to the development of an interrelated entanglement of spatial injustices through racially unequal, economically stratified, and tacitly biased practices of spatial production. 2 Edgar Pieterse, “Post-Apartheid Geographies in South Africa: Why Are Urban Divides so Persistent?,” lecture, “Interdisciplinary Debates on Development and Cultures: Cities in Development – Spaces, Conflicts and Agency,” University of Leuven, 2009. It is widely understood that the generational effects of these socio-spatial systems of segregation have had deep psycho-spatial consequences throughout the built-environment, 3 Nqobile Malaza, “Black Urban, Black Research: Why Understanding Space and Identity in South Africa Still Matters,” in Changing Space, Changing City: Johannesburg after Apartheid, ed. Philip Harrison et al. (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2014), 553–67. and will most likely continue to do so for generations to come.

While the nature of these tacitly biased forms of built-environment production are hard to quantify, the embodied feelings of distrust expressed between various ‘others’, 4 Teresa Dirsuweit, “The Fear of Others: Responses to Crime and Urban Transformation in Johannesburg,” in Changing Space, Changing City, ed. Harrison et al., 546. the over-control and securitisation of shared spaces, and an endemically uneven distribution of crucial spatial resources demonstrate how these systems are tacitly reinforced in South African cities. 5 Vanessa Watson, “Deep Difference: Diversity, Planning and Ethics,” Planning Theory 5, no. 1 (March 2006): 31–50. In support of this, Doreen Massey emphasises the importance of acknowledging the lived aspects of spatiality and the importance this acknowledgement plays in the shared lives of people: ‘the way we think about space matters. It influences our understandings of the world, our attitudes to others, our politics’. 6 Doreen Massey, Space, Place, and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 1.

Figure 9.1: The Apartheid City Model (Davies, 1983).

More specifically, the layers of unequally distributed infrastructure and prejudiced industry standards, combined with spatially embodied consumer-driven demand, have deeply entrenched these tacit biases within the spatial professions and disciplines – which are also products of these systems – entrusted to guide the design and development of the urban form. The individuals who make up this broader collection of practitioners are not faceless victims of their context, but real people with their own interrelated relationships to people and built form. As one such spatial practitioner, the author of this chapter, highlights, this reality is not an external critique of an ‘otherly’ location, but an equally complicit part of this system deeply situated within the milieu of living and practising in South African cities.

In Support of a Southern Feminist Approach

Recognising these interrelationships between the embedded tacit biases of the city-form and the embodied socio-spatial practices of a context such as South Africa leads to an important question around what can be done, and how to address this complex set of issues through the disciplinary framings and tools available. Traditional urban scholarship guides one towards global ideals of ‘best’ urban practice or form, but many contemporary scholars warn us of where these values are framed 7 Sujata Patel, “Is There a ‘South’ Perspective to Urban Studies?,” in The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, ed. Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield (New York: Routledge, 2014), 37–48. and how they are operationalised across vastly different contexts. This warning underlines an ongoing critical discussion around the forms of spatial knowledge that shape and guide contemporary urban research, and the need for more contextualised, indigenously-based, and localised values of internalising and theorising from place. 8 Ananya Roy, “Worlding the South: Towards a Post Colonial Urban Theory,” in The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, ed. Parnell and Oldfield, 9–20. These discussions centre around calls for more contextually responsible readings of space that are true to the locations where they exist, valued through the situated terms of the context that produce them, and actionable through the languages – spoken, gestured, and visual – that they are located in.

Such calls require approaches, methods, and techniques that operate through frameworks of practice that are often difficult to articulate outside of ‘Southern’ 9 Raewyn Connell, “Using Southern Theory: Decolonizing Social Thought in Theory, Research and Application,” Planning Theory 13, no. 2 (May 2014): 210–23. framings of contemporary research. Instead, emerging conceptual frameworks such as ‘Southern Urbanism’ 10 Abdou Maliq Simone, New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times (Cambridge: Polity, 2017). are available, and in the larger dissertation, being employed by the author as a more situated and contextually responsive armature to support the project’s research aims. This has been carried out to locate such intentions of addressing South African spatial injustices and initiate an enquiry that works through the challenges of practising within a post-colonial and post-Apartheid South African city.

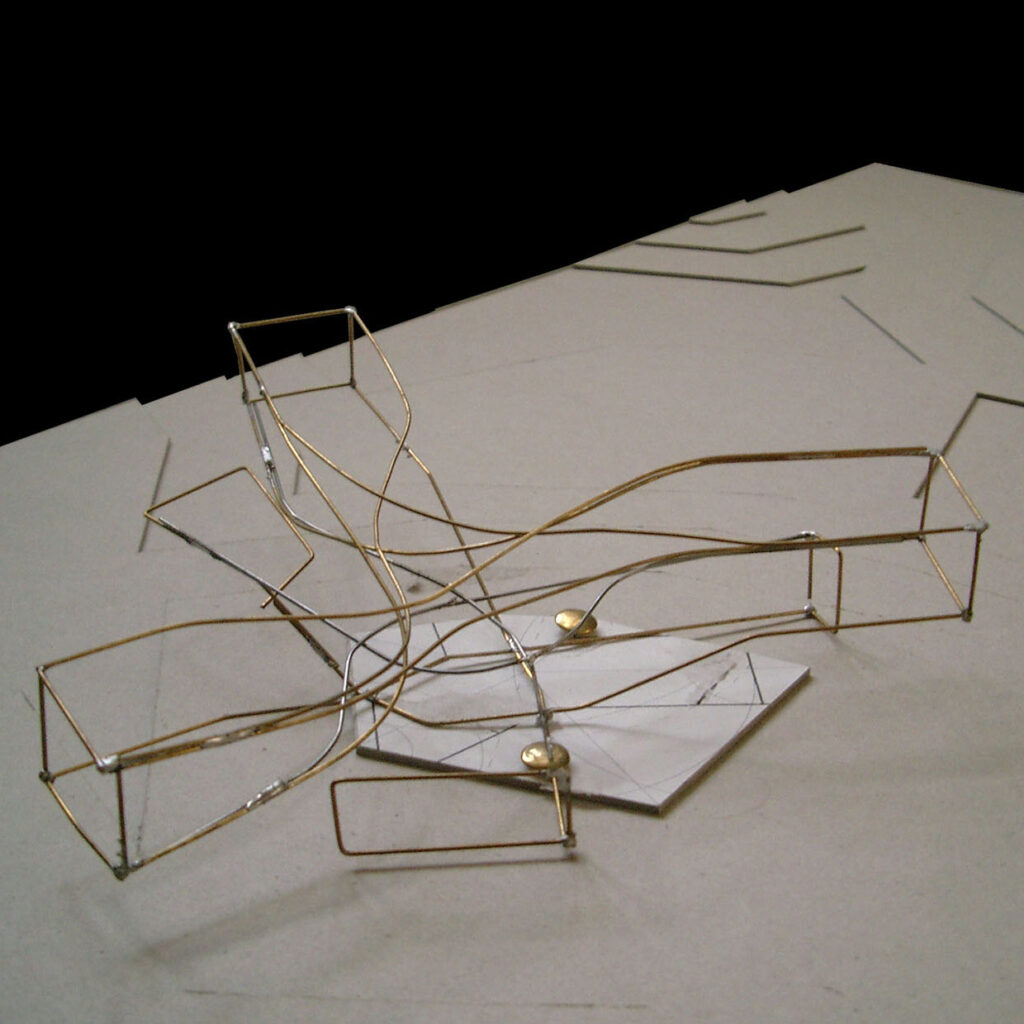

Figure 9.2: Developmental Gestures (Bennett, 2020)

When considering what a responsive architectural practice or, more appropriately, a spatial-design practice 11 An inclusive and transdisciplinary framing of design practices that works outside of professional and disciplinary boundaries that effect a social or Cartesian framing of ‘space’. could be in the face of such a complex set of local and global challenges, the locationally sensitive work being conducted through Southern Urban scholarship offers a Situated 12 Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (London: Routledge, 1991), 183–202. means to initially house such a methodological enquiry around how this can be done, while feminist readings on theoretical concepts of ‘Positionality’ 13 Wendy E. Rowe, “Positionality,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, ed. David Coghlan and Mary Brydon-Miller (London: SAGE Publications, 2014), 628 and ‘Praxis’ 14 Katherine R. Allen, “Feminist Theory, Method, and Praxis: Toward a Critical Consciousness for Family and Close Relationship Scholars,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 40, no. 3 (2023): 899–936; bell hooks, Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (New York: Routledge, 2003). are suggested in this chapter as a means of developing more actionable principles that speak to the positional and socio-spatial complexity of practising spatial-design in a ‘Southern’ city.

Urban scholar Vanessa Watson writes in support of such a Southern perspective on spatial practice. 15 Vanessa Watson, “The Case for a Southern Perspective in Planning Theory,” International Journal of E-Planning Research 3, no. 1 (2014): 23–37. Her work speaks to the relational recontextualisation of academic knowledge bases that has taken place across the humanities, recognised as the Southern Turn. 16 Connell, “Using Southern Theory.” Regarding urban studies, these are part of a collection of efforts that makes the case for the development of alternative theoretical resources against an existing dominant urban discourse. These sentiments are shared by scholars who, 17 Most commonly referenced is Ananya Roy’s offering of the term subaltern urbanism as a possibility for a different disposition towards Southern Theory. Jennifer Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development (New York: Routledge, 2013). in the face of neo-liberal and postcolonial discourses on cities, state that urban theoretical insights cannot be based on the experiences of a small selection of globally wealthy cities. In terms of the literature on Southern theories, these applied concepts are deeply concerned with practices of working ‘locationally’ 18 Teresa P. R. Caldeira, “Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, Transversal Logics, and Politics in Cities of the Global South,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35, no. 1 (2017): 3–20. from place and operating from the ‘periphery’, 19 Simone’s concept of the periphery is multivalent, and includes ideas of entanglements, spaces-in-between, and the concept of possibility. Simone, New Urban Worlds. and seek to exist beyond the epistemic hegemonies of relational ‘norths’. 20 Not a geographical north, but a relational hegemonic counterpoint. Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223–38. On this point of epistemic hegemony, it is important to articulate the author’s rationale for framing the larger dissertation through Southern principles as a positionally ethical 21 In reflection on Smith’s code of conduct for research. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999). means of acknowledging the ‘incommensurable limits’ 22 Wayne Yang and Eve Tuck, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40. of someone of their positionality to conduct critical decolonial academic work. 23 For this reason, the author acknowledges, but refrains from citing, texts by other decolonial scholars whose work is directed towards and in support of voices other than the author’s demographic position. This point is made to carefully acknowledge the distinction between decoloniality and decolonisation. Walter Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, “Decoloniality in / as Praxis Part One,” in On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018). The important link that has been identified between Southern and Decolonial literature is an acknowledgement of displaced communities of knowledge and the efforts required in rearticulating these knowledges through critical actions in addition to the conceptual displacement of localised academic vocabularies. In support of this, Gautam Bhan describes the ‘south’ as a relational condition. 24 Gautam Bhan, “Notes on a Southern Urban Practice,” Environment and Urbanization 31, no. 2 (January 2019): 639–54. Bhan carefully explains how it should not be seen as a geographical location, but as a set of moving peripheries in response to a more normative ‘northern’ hegemony on understanding the urban. 25 Bhan refers to the concept of ex-loci. Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff, Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving Toward Africa (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Framing a Practice Orientated Design-Based Enquiry

Drawing from concerns of location and responsive action in Southern theories, Positionality 26 Gillian Rose, “Situating Knowledges: Positionality, Reflexivities and Other Tactics,” Progress in Human Geography 21, no. 3 (1997): 305–20. as a concept for research practice grounds much of the larger dissertation that this chapter supports. The author’s concerns and framing of their own positionality within the larger study were deeply engaged with in earlier work, 27 Jhono Bennett, “Navigating the What-What: Spirit of the Order,” in “Species of Theses and Other Pieces,” ed. Meike Schalk, Torsten Lange, Elena Markus, Andreas Putz, and Tijana Stevanovic, special issue, Dimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge 2, no. 3 (April 2022): 229–45. but an important acknowledgement should be noted in a need for more situated 28 Haraway, “Situated Knowledges.” and positionally critical forms of knowledge production in post-colonial academic contexts. This is further expanded by the feminist operationalisations of Praxis, which call for a ‘translation of theory into action by working for social change locally, nationally, and globally’. 29 Allen, “Feminist Theory, Method, and Praxis,” 3. Similarly aligned scholars have expanded on these concepts and bring to this field more critically interpretative, actionable, and multi-locational concerns on situated knowledges in response to concerns of race, identity, and global power in the twenty-first century. In this regard, Lynette Hunter 30 Lynette Hunter, “Situated Knowledge,” in Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research: Scholarly Acts and Creative Cartographies, ed. Shannon Rose Riley and Hunter (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 151–53. Hunter makes reference to the contribution of Patricia Collins in the latter’s article, “Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought,” Social Problems 33, supplement 6 (1886): s14–s32. explains how such situated knowledge simultaneously refers to more tacit forms of understanding that exist both textually – what – and in action – how.

Building on the polymath Michael Polanyi’s work, 31 Michael Polanyi uses the example of tacitly recognising a face in a crowd by knowing the features of the face. He suggests that one can tacitly know something more comprehensive by focusing on the particulars of the facts, which enables one to ‘know more than we can tell’. See Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). the sociologist Harry Collins offers a framing of three different forms of tacit knowledge: the weak, ‘Relational Tacit Knowledges’; the medium, ‘Somatic Tacit Knowledges’; and the strong, ‘Collective Tacit Knowledges’. 32 Harry Collins, Tacit & Explicit Knowledge (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010). These collectively biased knowledge practices manifest in the built environment in contextually specific ways that only a handful of spatial disciplines are equipped to engage with, namely those concerned with the actioned subjectivities of design and making. This systemic aspect of spatial ‘knowledge-how’ in the built environment carries implications that reach beyond that of a single building’s scope, as these individual interventions ultimately add up to larger shared collective system of space that form the South African towns and cities. The different articulations of practice and theory are an important lens for this study, as acknowledged by Polanyi, who describes the importance of recognising the varied aspects of tacit knowledge at different levels of society, but points out that the individual body remains the ultimate instrument of external knowledge, whether practical or intellectual. 33 Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension. It is these themes of Collective Tacit Knowledges that this study draws most strongly from, specifically the forms of knowledge that are considered more collectively biased or prejudiced through the production of shared urban spaces, in this case South African cities.

In outlining the possible modalities for engaging with such forms of tacit knowledge, the definition of what constitutes design – or even practice – used by the author differs slightly from contemporary writing on design research. 34 Nigel Cross, “Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science,” Design Issues 17, no. 3 (Summer (2001): 49–55; Linda N. Groat and David Wang, Architectural Research Methods (Hoboken: Wiley, 2013). Instead, they align more closely with built-environment practitioner and scholar Donald Schön’s critique of the positivist aspects of traditional ideas of design 35 Donald A. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 2013). towards more iterative and transformative concerns on iterative engagement through the idea of repair and maintenance. While traditional design-led research can be understood as a knowledge-focused methodology that integrates design practices and processes to examine what can be learned through practitioner action, 36 Simon Grand and Wolfgang Jonas, eds., Mapping Design Research: Positions and Perspectives (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2012); Abel, Design Research. design researcher Amollo Ambole 37 Amollo Ambole, “Rethinking Design Making and Design Thinking in Africa,” Design and Culture 12, no. 3 (2020): 331–50. makes an important case for decentring the way we understand design from a ‘northern’ perspective.

In this regard, Schön’s own work on such reflective approaches to practice makes an important distinction between research and practice, but offers iterative reflection as a means of interpreting practice and extracting the more explicit forms of what he classifies as research. In this regard, a practice-orientated approach is considered to involve an enquiry into methods, systems, programmes, and policies of professional practice, with the ultimate aim to employ research knowledge towards bettering the implementation of practice. 38 Nick J. Fox, “Practice-Based Evidence: Towards Collaborative and Transgressive Research,” Sociology 37, no. 1 (2003): 81–102. Towards this goal, the larger dissertation frames the research enquiry as practice-oriented, but design-based.

Locating Practice Values in a Southern City

The Post-Post City

Johannesburg is a city that was never meant to be. Its locational origins were determined by the randtjieslaagte, a small section of un-surveyed land, 39 The name given to the uitvolgrond – left over land – between surveys. and was built so rapidly and in response to such extractive industrial forces that to this day we do not know which Johannes the name of the city refers to. 40 Clive M. Chipkin, Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950 (Johannesburg: STE Publishers, 2008). Joburg is not located near any natural water resources, 41 Joburg draws its major water via a dam that is supplied by South Africa’s neighbouring country, Lesotho. and the urban form that most directly influenced the city was shaped by the inverted splash of a meteor that struck this part of the earth 2 billion years ago. This cosmic impact forced the gold seam closer to the surface, which was discovered in the mid-nineteenth century and played a key role in the British invasion of the independent Boer Republic, the Transvaal, decades later. The East/West axis of the meteorologically informed geology of the ‘mining belt’ – a strip of industrial infrastructure built in response to the gold – originally split Joburg across a clear northern (affluent) and southern (labour force) divide. The human capital that shaped the spatial formation of Joburg reflects the multitude of national, ethnic, and cultural bodies and voices that each played their part in producing a 120-year-old city that today is one of the most unequal metropolises in the world. 42 South African Cities Network SACN, State of Cities Reports – SA Cities (4th Edition), Knowledge Hub, 2016.

In 1994, the first democratic elections in South Africa were held, ushering in the beginning of the ‘new South Africa’ under what Archbishop Desmond Tutu termed the Rainbow Nation. 43 Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa. The newly revoked pass laws 44 Apartheid-era laws that controlled and curtailed the movement of non-White South Africans. and the dismantling of the Apartheid State saw a mass-influx of people to urban centres among a host of internal migrations from various groupings of South Africa. As the largest city in South Africa, Joburg became a centre for this urban influx and continued its role as the promised ‘city of gold’. Joburg was again a focal point of political shifts as the leaders of the #FeesMustFall movement guided the protesting students through the streets of the city to the seat of government in the nation’s capital, Pretoria, to demand their right to the country’s resources – through access to higher education 45 Rekgotsofetse Chikane, Breaking a Rainbow, Building a Nation: The Politics Behind #MustFall Movements (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2018). –against increasing socio-economic disparity, racial inequality, and the call for a decolonised education system.

Figure 9.3: Times Magazine Cover (Times, 2019)

This period saw the end of the rhetoric of Rainbowism 46 The colloquial term for the disregard or sugar-coating of race-related issues around the mantra of the Rainbow Nation. Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, “The Game’s the Same: ‘MustFall’ moves to Euro-America,” in Fees Must Fall: Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa, ed. Susan Booysen (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016), 74–86. and brought to the fore a more critical discourse on social justice that championed the importance of a truly decolonial reconfiguration of post-Apartheid academia, society, and South Africa more broadly. It appears that the country is currently in a phase of renegotiating their framed epoch as, at the time of writing, there is not a ‘new’ framing concept in use by any part of South African society. For now, the author has borrowed from the colloquial conceptualisation of time that describes Now as this very moment, Just-Now as an indefinite period between a few hours and few days, and Now-Now as a time that is coming, but may never come: the Post-Post Apartheid city.

Southern Revisitations

Although Johannesburg was built before the Group Areas Act 47 The Group Areas Act was the legal policy that required people of different government-classified race groups to live in different government-defined areas in either Townships or rural Homelands known as Bantustans, located hundreds of kilometres from urban centres. was put in force in the 1950s, the separative patterns of labour, industry, and housing put in place by both the Traansvaal government 48 The Traansvaal was the independent Boer Republic that preceded the colonial Union of South Africa, formed in 1911. Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa. and, later, British colonial forces preceded an urban structure that was later entrenched through the control of labour between the city centre, the townships, 49 Townships were the areas designated for non-White South Africans. During Apartheid, Black South Africans were legally denied access to ‘White South Africa’. Today, the word is used interchangeably with poor, non-White areas. and the rural homelands through the larger Apartheid system. The twentieth-century Apartheid city model, implemented by law, very specifically separated inhabitants and users along strict zoning and racial definitions as set out by city planners and mandated by the national government. Each adopted an internal core – a Central Business District (CBD) – that acted as a hub between industrial areas, outlying white neighbourhoods, and non-white townships, and severely controlled access times, modes, and users. 50 R. J. Davies, “The Spatial Formation of the South African City,” GeoJournal 2, supplement 2 (1981): s59–s72.

The model employed various natural and manmade ‘buffers’ to separate these areas that included industrial zones, rivers, mountains and, in the case of Johannesburg, the unusable extracted ore from mining known locally as the ‘mine dumps’.

Figure 9.4: The Apartheid National Segregation (Davies, 1983)

Apartheid-era townships were placed at the edges of these urban centres and operated as dormitory towns to which homeland residents with families would be allocated by the government; as a result, they were severely underserviced. In addition to the township housing, several multi-storeyed ‘hostel’ housing options were allocated to those looking for work near cities. These systems allowed single men or women from homeland areas to apply for state-controlled housing in the form of multi-storey hostels in order to work in the mines and industry of the city and surrounding areas. 51 Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa. These hostels were typically divided ‘culturally’ along South Africa’s larger tribal groupings and further separated by gender.

Beyond the technical challenges inherent in this work, these efforts continue to be mired by detrimental, tacitly-embedded stigmas and embodied perceptions which undermine much of the work undertaken in this sector. This observation was more broadly captured in the larger dissertation during a series of reflective ‘revisitations’ by the author through their own practice work undertaken with a Zulu men’s hostel, Denver, from within their role within a small practice collective. 52 Aformal Terrain – AT – was a collaborative and collective architecture/urbanism/landscape group that closely engaged with complex urban conditions. This collaboration worked for many years with the leadership of Denver, providing socio-technical support towards the ‘upgrading’ of the informal settlement through the governmental programmes in place. These experiences were revisited through the Site-Writing 53 Jane Rendell, “Critical Spatial Practice: A Feminist Sketch of some Modes and what Matters,” in Feminist Practices, ed. Lori Brown (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 17–55. methods developed in the larger dissertation, captured in a series of visual exercises entitled ‘Re-Returning to the Mining Belt’ (see Fig. 9.4–8), which additionally drew from a decade of work in similar contexts across South Africa.

Figure 9.5: Mining Belt Revisitations 1 (Bennett, 2021)

Figure 9.6: Mining Belt Revisitations 2 (Bennett, 2021)

Figure 9.7: Mining Belt Revisitations 3 (Bennett, 2021)

Figure 9.8: Mining Belt Revisitations 4 (Bennett, 2021)

Figure 9.9: Mining Belt Revisitations 5 (Bennett, 2021)

Sites such as Denver actively blur already tacitly-biased categories by being both an ‘informal settlement’ as well as in the ‘occupied building’ category. The socially collective, physically supportive, and contextually incremental means of managing people and built infrastructure employed by Denver residents that were revealed by this revisit to Denver demonstrate what ideas of both social and physical repair and contextualised concepts of maintenance could mean outside of the ‘formalised/northern’ readings of infrastructure and built form. Typically, they provide more affordable and socially cohesive living opportunities for those who cannot afford safer options, but at a potentially high risk of danger and precarious living conditions. This observation is in direct contradiction to how top-down upgrading efforts tend to ignore the existing leadership and social maintenance structures, side-line existing social patterns, and impose contextually-sensitive systems in place of what is currently at work: implementing physical ‘solutions’ that often quickly fall into physical disrepair shortly after being imposed upon a partly willing group of people. This sentiment is not intended to romanticise the living conditions of informal settlements, but rather to point out that the values that underpin their continued existence and growth remain unengaged with, largely due to what is considered ‘best global’ practice by local governmental actors for an urban practice such as ‘informal settlement’ upgrading. Such ‘northern’ values are often superimposed upon local conditions through governmental and professional practitioners’ top-down approaches. 54 Nabeel Hamdi, Small Change: About the Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities (London: Earthscan, 2013).

Locating a Post-Post Positional Praxis

Towards a Reparative Praxis

In response to these embedded tacit systems of socio-spatial bias in the built form, embodied through city-practitioners, the author has seen in their Site-Writing investigations how such systems manifest in anti-poor, anti-foreign national, and anti-‘informality’ undertows that are deeply present in this sector of urban spatial practice. 55 Marie Huchzermeyer, Cities with ‘Slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa (Claremont, SA: UCT Press, 2011). As there is no technical or legal definition of ‘informality’ in South Africa – as engaged with in the ‘Spirit of the Order’ 56 Bennett, “Spirit of the Order: Navigating the What-What.” revisitation in the larger dissertation – these tacitly biased readings are a strong example of how Collective Tacit Knowledge in socio-spatial systems shapes the understandings of what is acceptable within a city, and what is undesired. Such readings draw much basis from localised ‘northern’ internalisations of ‘good’ urbanity and who has the right to the resources of the post-post South African city. Such contradictory understandings and actions towards what are termed ‘upgrading’, as revealed in the larger dissertation, betray these prejudices, and often perpetuate the very inhumane living conditions through actions such as eviction or sabotage of people’s homes to encourage their departure from an area. These misreadings allude to a very present cognitive dissonance and reading of the people and city that the author feels is best explained by Edward Said’s term, imaginative geographies, 57 Edward W. Said, Orientalism (London: Vintage, 1979) 97. a concept that speaks to the collective biases of those outside of a particular spatial reality and the perpetuating factors of societal power that continue to support a prejudiced view of a place.

Figure 9.10: Constellation’s of Spatial Practice (Bennett, 2022)

There is an acknowledged, seemingly contradictory approach that is being outlined in this chapter. On the one hand, the author asks the reader to recognise the cross-positional complexities of being situated within an embedded system and the embodied tacit bias of being situated in a fundamentally unjust socio-spatial system. On the other hand, the reader is also asked to take seriously the nuance and located values of urban paradigms outside of a ‘northern’ framing of the city towards a more contextually attuned modality of practice within a post-post city, such as Johannesburg. It is at the intersection of these contradictions that the author highlights why the importance of a critically-situated, creative, and design-based approach is such a crucial means for interrogating these conditions and responsibly proposing ways of staying with 58 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016). these complexities. This approach requires one to work through these challenges by means of a considered and iterative Praxis, based on the feminist application of actioning theory towards social change as a means of tying such theoretical intent back into context.

Among the various concepts that are recognised in the growing field of Southern Urbanism, ideas of ‘Repair’ 59 Bhan, “Notes on a Southern Urban Practice,” 7. within Southern cities which hold to more collective forms of both physical and social maintenance have emerged as an imperative line of propositional framing. In support of this development, more social-justice concepts of ‘Reparative Practices’ 60 Vanesa Caston Broto, Linda Westman, and Ping Huang, “Reparative Innovation for Urban Climate Adaptation,” Journal of the British Academy 9, supplement 9 (October 2021): s205–s18. have found their way into the emerging model of Praxis 61 As understood as a link of action to reflection in the work of bell hooks and Paulo Freire: bell hooks, Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope; Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (London: Penguin, 2017). being developed by the author, and are framed in the larger dissertation as a means of navigating the complexities of being part of a location’s endemic issues and drawing theoretical basis from within. This is further supported by the initial findings from the field work of the larger dissertation, ‘Constellations of Spatial Practice’, where interviewed spatial-design practitioners described how they iteratively and reflexively ask themselves how they should frame the project between their partners and the different agents of change – i.e., government, private sector, and support NGOs – to channel and scaffold the support they have been providing. These findings have been initially interpreted through a praxis tool, ‘A Spatial Practice Phrase Book’ 62 This tool has been structured as a ‘Phrase Book’ to allow for multiple situated interpretations of local concepts and terms, guided by Southern principle of location and place. (Fig. 9.11). These practitioners shape their actions to respond on the grass-roots human scale while speaking to the higher order principles of sustainable city-making in a Southern African urban context. These actions were seen to be carried out over many years, and required a relationship to Repair that went beyond simple physical maintenance and spoke to the socio-spatial values of social repair through iterative social engagement and constant re-evaluation through checking in.

Regarding the case offered in this study, the author believes that the daily proximities of such inequality in a context like South Africa over generations – and generations to come – requires such an iterative and simultaneous layered approach of understanding and proactive action towards a spatial-design praxis of both reflection and action. Although the study focuses on post-post South Africa and similar Southern cities, the positionally critical and systemically complex approaches needed to both understand and work through such a tacitly biased system of spatial injustice are not limited to this context. This investigation reveals not only the relevance of such an enquiry to South Africa, but offers a methodological means of interrogating other embedded and embodied forms of spatial inequality and biased Collective Tacit Knowledge across the world. The larger arc of the dissertation’s research holds the potential to reveal forms of more connective tacit knowledges – in the face of prejudiced built forms – that exist through ways of making and maintaining spaces through ideas of social and physical repair across a rapidly urbanising world.

Figure 9.11: A Spatial Phrase Book (Bennett, 2021)

Bibliography

- Abel, Chris. 2011. Design Research. CTBUH Journal.

- Allen, Katherine R. “Feminist Theory, Method, and Praxis: Toward a Critical Consciousness for Family and Close Relationship Scholars.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 40, no. 3 (2023): 899–936.

- Ambole, Amollo. “Rethinking Design Making and Design Thinking in Africa.” Design and Culture 12, no. 3 (2020): 331–50.

- bell hooks. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Bennett, Jhono. “Navigating the What-What: Spirit of the Order.” In “Species of Theses and Other Pieces,” ed. Meike Schalk, Torsten Lange, Elena Markus, Andreas Putz, and Tijana Stevanovic.

- Special issue, Dimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge 2, no. 3 (April 2022): 229–45.

- Bhan, Gautam. “Notes on a Southern Urban Practice.” Environment and Urbanization 31, no. 2 (January 2019): 639–54.

- Broto, Vanesa Caston, Linda Westman, and Ping Huang. “Reparative Innovation for Urban Climate Adaptation.” Journal of the British Academy 9, supplement 9 (October 2021): s205–s18.

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. “Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, Transversal Logics, and Politics in Cities of the Global South.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35, no. 1 (2017): 3–20.

- Chikane, Rekgotsofetse. Breaking a Rainbow, Building a Nation: The Politics Behind #MustFall Movements. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2018.

- Chipkin, Clive M. Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950. Johannesburg: STE Publishers, 2008.

- Collins, Patricia. “Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought.” Social Problems 33, supplement 6 (1886): s14–s32

- Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving Toward Africa. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Connell, Raewyn. “Using Southern Theory: Decolonizing Social Thought in Theory, Research and Application.” Planning Theory 13, no. 2 (May 2014): 210–23.

- Cross, Nigel. “Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science.” Design Issues 17, no. 3 (Summer (2001): 49–55.

- Davies, R. J. “The Spatial Formation of the South African City.” GeoJournal 2, supplement 2 (1981): s59–s72.

- Dirsuweit, Teresa. “The Fear Of Others: Responses To Crime And Urban Transformation In Johannesburg.” In Changing Space, Changing City: Johannesburg after Apartheid, edited by Philip

- Harrison et al., 546–52. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2014.

- Fox, Nick J. “Practice-Based Evidence: Towards Collaborative and Transgressive Research.” Sociology 37, no. 1 (2003): 81–102.

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin, 2017.

- Grand, Simon, and Wolfgang Jonas, eds. Mapping Design Research: Positions and Perspectives. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2012.

- Groat, Linda N., and David Wang. Architectural Research Methods. Hoboken: Wiley, 2013.

- Hamdi, Nabeel. Small Change: About the Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities. London: Earthscan, 2013.

- Haraway, Donna J. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 183–202.

- London: Routledge, 1991.

- Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

- Huchzermeyer, Marie. Cities with ‘Slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. Claremont, SA: UCT Press, 2011.

- Hunter, Lynette. “Situated Knowledge.” In Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research: Scholarly Acts and Creative Cartographies, edited by Shannon Rose Riley and Hunter, 151–53. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Mabin, Alan, and Dan Smit. “Reconstructing South Africa’s Cities? The Making of Urban Planning 1900–2000.” Planning Perspectives 12, no. 2 (1997): 193–223.

- Malaza, Nqobile. “Black Urban, Black Research: Why Understanding Space and Identity in South Africa Still Matters.” In Changing Space, Changing City: Johannesburg after Apartheid, edited by

- Philip Harrison et al., 553–67. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2014.

- Massey, Doreen. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

- Mignolo, Walter, and Catherine E. Walsh. “Decoloniality in / as Praxis Part One.” In On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, 1–14. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Mpofu-Walsh, Sizwe. “The Game’s the Same: ‘MustFall’ moves to Euro-America.” In Fees Must Fall: Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa, edited by Susan Booysen, 74–86. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016.

- Patel, Sujata. “Is There a ‘South’ Perspective to Urban Studies?” In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, edited by Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield, 37–48. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Pieterse, Edgar. “Post-Apartheid Geographies in South Africa: Why Are Urban Divides so Persistent?” Lecture, “Interdisciplinary Debates on Development and Cultures: Cities in Development – Spaces, Conflicts and Agency,” University of Leuven, 2009.

- Rendell, Jane. “Critical Spatial Practice: A Feminist Sketch of some Modes and what Matters.’ In Feminist Practices, edited by Lori Brown, 17–55. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

- Robinson, Jennifer. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Rose, Gillian. “Situating Knowledges: Positionality, Reflexivities and Other Tactics.” Progress in Human Geography 21, no. 3 (1997): 305–20.

- Rowe, Wendy E. “Positionality.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, edited by David Coghlan and Mary Brydon-Miller. London: SAGE Publications, 2014. 15-19

- Roy, Ananya. “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research35, no. 2 (2011): 223–38.

- Roy, Ananya. “Worlding the South: Towards a Post Colonial Urban Theory.” In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, edited by Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield, 9–20. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- SACN, South African Cities Network. 2016. State of South African Cities Report, ’16. Edited by Kristina Davidson and Geci Karuri-Sebina. Johannesburg, South Africa: e South African Cities Network. http://www.sacities.net/the-state-of-south-african-cities-report-2016.

- Said, Edward W. Orientalism. London: Vintage, 1979.

- Schön, Donald A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books, 2013.

- Simone, Abdou Maliq. New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times. Cambridge: Polity, 2017.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books, 1999.

- Thompson, Leonard, and Lynn Berat. A History of South Africa. Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2014.

- Watson, Vanessa. “The Case for a Southern Perspective in Planning Theory.” International Journal of E-Planning Research 3, no. 1 (2014): 23–37.

- Watson, Vanessa. “Deep Difference: Diversity, Planning and Ethics.” Planning Theory 5, no. 1 (March 2006): 31–50.

- Yang, Wayne, and Eve Tuck. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

- Alan Mabin and Dan Smit, “Reconstructing South Africa’s Cities? The Making of Urban Planning 1900–2000,” Planning Perspectives 12, no. 2 (1997): 193–223; Leonard Thompson and Lynn Berat, A History of South Africa (Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2014). 56 -125

- Edgar Pieterse, “Post-Apartheid Geographies in South Africa: Why Are Urban Divides so Persistent?,” lecture, “Interdisciplinary Debates on Development and Cultures: Cities in Development – Spaces, Conflicts and Agency,” University of Leuven, 2009.

- Nqobile Malaza, “Black Urban, Black Research: Why Understanding Space and Identity in South Africa Still Matters,” in Changing Space, Changing City: Johannesburg after Apartheid, ed. Philip Harrison et al. (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2014), 553–67.

- Teresa Dirsuweit, “The Fear of Others: Responses to Crime and Urban Transformation in Johannesburg,” in Changing Space, Changing City, ed. Harrison et al., 546.

- Vanessa Watson, “Deep Difference: Diversity, Planning and Ethics,” Planning Theory 5, no. 1 (March 2006): 31–50.

- Doreen Massey, Space, Place, and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 1.

- Sujata Patel, “Is There a ‘South’ Perspective to Urban Studies?,” in The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, ed. Susan Parnell and Sophie Oldfield (New York: Routledge, 2014), 37–48.

- Ananya Roy, “Worlding the South: Towards a Post Colonial Urban Theory,” in The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, ed. Parnell and Oldfield, 9–20.

- Raewyn Connell, “Using Southern Theory: Decolonizing Social Thought in Theory, Research and Application,” Planning Theory 13, no. 2 (May 2014): 210–23.

- Abdou Maliq Simone, New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times (Cambridge: Polity, 2017).

- An inclusive and transdisciplinary framing of design practices that works outside of professional and disciplinary boundaries that effect a social or Cartesian framing of ‘space’.

- Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (London: Routledge, 1991), 183–202.

- Wendy E. Rowe, “Positionality,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Action Research, ed. David Coghlan and Mary Brydon-Miller (London: SAGE Publications, 2014), 628

- Katherine R. Allen, “Feminist Theory, Method, and Praxis: Toward a Critical Consciousness for Family and Close Relationship Scholars,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 40, no. 3 (2023): 899–936; bell hooks, Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (New York: Routledge, 2003).

- Vanessa Watson, “The Case for a Southern Perspective in Planning Theory,” International Journal of E-Planning Research 3, no. 1 (2014): 23–37.

- Connell, “Using Southern Theory.”

- Most commonly referenced is Ananya Roy’s offering of the term subaltern urbanism as a possibility for a different disposition towards Southern Theory. Jennifer Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development (New York: Routledge, 2013).

- Teresa P. R. Caldeira, “Peripheral Urbanization: Autoconstruction, Transversal Logics, and Politics in Cities of the Global South,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35, no. 1 (2017): 3–20.

- Simone’s concept of the periphery is multivalent, and includes ideas of entanglements, spaces-in-between, and the concept of possibility. Simone, New Urban Worlds.

- Not a geographical north, but a relational hegemonic counterpoint. Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, no. 2 (2011): 223–38.

- In reflection on Smith’s code of conduct for research. Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 1999).

- Wayne Yang and Eve Tuck, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

- For this reason, the author acknowledges, but refrains from citing, texts by other decolonial scholars whose work is directed towards and in support of voices other than the author’s demographic position. This point is made to carefully acknowledge the distinction between decoloniality and decolonisation. Walter Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, “Decoloniality in / as Praxis Part One,” in On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018).

- Gautam Bhan, “Notes on a Southern Urban Practice,” Environment and Urbanization 31, no. 2 (January 2019): 639–54.

- Bhan refers to the concept of ex-loci. Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff, Theory from the South: Or, How Euro-America Is Evolving Toward Africa (New York: Routledge, 2016).

- Gillian Rose, “Situating Knowledges: Positionality, Reflexivities and Other Tactics,” Progress in Human Geography 21, no. 3 (1997): 305–20.

- Jhono Bennett, “Navigating the What-What: Spirit of the Order,” in “Species of Theses and Other Pieces,” ed. Meike Schalk, Torsten Lange, Elena Markus, Andreas Putz, and Tijana Stevanovic, special issue, Dimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge 2, no. 3 (April 2022): 229–45.

- Haraway, “Situated Knowledges.”

- Allen, “Feminist Theory, Method, and Praxis,” 3.

- Lynette Hunter, “Situated Knowledge,” in Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research: Scholarly Acts and Creative Cartographies, ed. Shannon Rose Riley and Hunter (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 151–53. Hunter makes reference to the contribution of Patricia Collins in the latter’s article, “Learning from the Outsider Within: The Sociological Significance of Black Feminist Thought,” Social Problems 33, supplement 6 (1886): s14–s32.

- Michael Polanyi uses the example of tacitly recognising a face in a crowd by knowing the features of the face. He suggests that one can tacitly know something more comprehensive by focusing on the particulars of the facts, which enables one to ‘know more than we can tell’. See Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

- Harry Collins, Tacit & Explicit Knowledge (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension.

- Nigel Cross, “Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science,” Design Issues 17, no. 3 (Summer (2001): 49–55; Linda N. Groat and David Wang, Architectural Research Methods (Hoboken: Wiley, 2013).

- Donald A. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (New York: Basic Books, 2013).

- Simon Grand and Wolfgang Jonas, eds., Mapping Design Research: Positions and Perspectives (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2012); Abel, Design Research.

- Amollo Ambole, “Rethinking Design Making and Design Thinking in Africa,” Design and Culture 12, no. 3 (2020): 331–50.

- Nick J. Fox, “Practice-Based Evidence: Towards Collaborative and Transgressive Research,” Sociology 37, no. 1 (2003): 81–102.

- The name given to the uitvolgrond – left over land – between surveys.

- Clive M. Chipkin, Johannesburg Transition: Architecture and Society from 1950 (Johannesburg: STE Publishers, 2008).

- Joburg draws its major water via a dam that is supplied by South Africa’s neighbouring country, Lesotho.

- South African Cities Network SACN, State of Cities Reports – SA Cities (4th Edition), Knowledge Hub, 2016.

- Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa.

- Apartheid-era laws that controlled and curtailed the movement of non-White South Africans.

- Rekgotsofetse Chikane, Breaking a Rainbow, Building a Nation: The Politics Behind #MustFall Movements (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2018).

- The colloquial term for the disregard or sugar-coating of race-related issues around the mantra of the Rainbow Nation. Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, “The Game’s the Same: ‘MustFall’ moves to Euro-America,” in Fees Must Fall: Student revolt, decolonisation and governance in South Africa, ed. Susan Booysen (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2016), 74–86.

- The Group Areas Act was the legal policy that required people of different government-classified race groups to live in different government-defined areas in either Townships or rural Homelands known as Bantustans, located hundreds of kilometres from urban centres.

- The Traansvaal was the independent Boer Republic that preceded the colonial Union of South Africa, formed in 1911. Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa.

- Townships were the areas designated for non-White South Africans. During Apartheid, Black South Africans were legally denied access to ‘White South Africa’. Today, the word is used interchangeably with poor, non-White areas.

- R. J. Davies, “The Spatial Formation of the South African City,” GeoJournal 2, supplement 2 (1981): s59–s72.

- Thompson and Berat, A History of South Africa.

- Aformal Terrain – AT – was a collaborative and collective architecture/urbanism/landscape group that closely engaged with complex urban conditions.

- Jane Rendell, “Critical Spatial Practice: A Feminist Sketch of some Modes and what Matters,” in Feminist Practices, ed. Lori Brown (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 17–55.

- Nabeel Hamdi, Small Change: About the Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities (London: Earthscan, 2013).

- Marie Huchzermeyer, Cities with ‘Slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa (Claremont, SA: UCT Press, 2011).

- Bennett, “Spirit of the Order: Navigating the What-What.”

- Edward W. Said, Orientalism (London: Vintage, 1979) 97.

- Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Bhan, “Notes on a Southern Urban Practice,” 7.

- Vanesa Caston Broto, Linda Westman, and Ping Huang, “Reparative Innovation for Urban Climate Adaptation,” Journal of the British Academy 9, supplement 9 (October 2021): s205–s18.

- As understood as a link of action to reflection in the work of bell hooks and Paulo Freire: bell hooks, Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope; Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (London: Penguin, 2017).

- This tool has been structured as a ‘Phrase Book’ to allow for multiple situated interpretations of local concepts and terms, guided by Southern principle of location and place.