Return to archive

title

COMMON GROUND. Discursive Orders in Architecture

author

Margitta Buchert

Abstract

Is it possible to characterize the relation of architecture and science, if it is not derived from established scientific conventions? This essay highlights one field of the multifaceted spectrum, which pops up in the context of this question, a field, which can be observed when expanding the focus from science to knowledge and processes of its formation and transformation. Focal point will be the question where and in which ways knowledge appears and marks a `common ground´. The investigations are revolved around the most important field of thematisation and mediation of architectural reality at the beginning of the 21st century to be found globally, the International Architecture Biennale, which takes place in Venice in a two year cycle. Furthermore special attention will be riveted on the biennale of 2012, which was dedicated to the theme `Common Ground´. The following notions are enmeshed with the consideration, that with a presentation and uncovering of knowledge and communication on it, we have here a kind of discourse in architecture that might not only process attitudes and a stabilization of the discipline, but also provides triggers for generic processes of scientific contexts and basic understandings of research and design in architecture.

This text was first published 2013, in: Common Ground. Systems of Discourse in Architecture. Diskursive Ordnungen in der Architektur, in: Fakultät für Architektur und Landschaft der LUH (ed.), Hochweit 13, Hannover: Internationalismus 2013, 9-17

How can the relation between architecture and science be characterized if we, first of all, do not start from established scientific conventions? From the very diverse spectrum that opens up with questions of this kind, fields are being focused on here that extend the view from science to areas of knowledge and its formation and transformation processes. These considerations are accompanied by the question of where and how the production of knowledge appears in architecture and marks a ‘common ground’. (fig.1)For test purposes, this will be examined using the example of the most important globally oriented thematization and mediation of architecture-reality at the beginning of the 21st century, the Venice Biennale, which takes place every two years. Moreover, special attention is paid to the Architecture Biennale of 2012, which was dedicated to the subject area of ‘Common Ground’. In various ways, the creative generation of knowledge and its communication will be observed as a phenomenon close to science, which not only expands the understanding of architecture and contributes to its development, but also provides impulses for scientific research contexts and basic understandings.

Discursive Practices

Many science-theorical and also political discussions of the last decades pointed out that with the fundamental analyzing and understanding of different, also unfamiliar ways of knowledge genesis, foundations for future potentials of the knowledge society and science can be discovered. 1 Cf. e.g. Michael Gibbons et al., Wissenschaft neu denken. Wissen und Öffentlichkeit im Zeitalter der Ungewissheit, Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft 2005, passim Architecture as an integrative discipline includes technical, aesthetic, economic, ecological and socio-cultural components. The related research areas include engineering, natural and economic sciences as well as human and cultural sciences. A variety of perspectives, conventions and guiding themes are characteristical to each specific field of research. Designing in architecture or design as well as artistic creation in the various visual and performing arts are controversially discussed as genuine empirical research tools and possibilities. 2 Cf. BIRD/Ralf Michel (ed.), Design reserach now! Essays and selected projects, Basel u.a.: Birkhäuser 2007, passim; Sabine Ammon/Eva Maria Froschauer (ed.), Wissenschaft Entwerfen. Vom forschenden Entwerfen zur Entwurfsforschung der Architektur, München: Wilhelm Fink 2013, passim

In order to extend basic understandings in these regards, contextualization with conceptual, critical, and curatorial practices can broaden horizons and provide impulses. These platforms of architectural productivity are found in the realm of both everyday professional practice and academic areas of activity, in addition to the field of design, central to architecture, and applied building and planning practice complexes. As interactively connected with these core areas, they form components of the architectural discipline that contribute to its self-understanding as well as to its epistemological genesis. 3 Cf. Felicity D. Scott, Operating platforms, in Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 65-69 The joint integration of the various segments into fields of knowledge formation is examined here in a tentative approach, against the background of the meaning and significance of discourse analysis as developed from works by Michel Foucault. 4 Michel Foucault, Die Ordnung der Dinge, 8th ed. Frankfurt a. Main: Suhrkamp 1989, esp. 24-28; Michel Foucault, Archäologie der Wissenschaft, 3rd ed. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1998, esp. 85-87, Andrea Kottmann/Hartmut Rosa/David Strecker, Soziologische Theorien, UTB: Stuttgart 2007, 283 With the discourse, a concept for understanding research and science as well as the complex systems of knowledge and reality production was outlined: Widespread notions of discourse as verbal argumentation in the sense of discussion or methodical presentation of a topic are expanded to include various practices in science and culture which influence discursive formations and have a knowledge- and insight-generating effect, and guide and promote orientation and positioning. 5 Cf. e.g. Michel Foucault, AW, op. cit. (note 4), esp. 68-74 The generative character of these practices in relation to knowledge building and reality construction plays a formative role. 6 Cf. Hannelore Bublitz, Diskurs, Bielefeld: Transcript 2002, esp. 56-60

Venice Architectural Biennials

The Venice Architecture Biennale can be described as such a practice. After architectural themes were presented for the first time in the mid-1970s through the efforts of architect Vittorio Gregotti in the neighborhood or as part of the art biennials with Venice-related or historical exhibitions, Paolo Portoghesi conceived the first independent architecture biennial in 1980. 7 For this and for the following cf. Aaron Levy/William Menking, Architecture on display. On the history of the Venice Biennale of Architecture, London: Architectural Association 2010, from 12 and passim With the theme ‘La presenza del passato’, in addition to the presentation of current projects by international architects through plans, models and photographs in the central pavilion of the Giardini, which had served as art biennial grounds since 1895, a 1:1 project was shown on the water in front of the old town, the Teatro del Mondo designed by Aldo Rossi, which brought the Venetian tradition of floating theaters up to date. In addition, the empty Corderie building in the Arsenale area of the city of Venice was included now for the first time. Already the entrance of this large three-aisled, 316 m long Corderie with 84 round pillars had been transformed by Aldo Rossi with a portal installation. Other contributions by international architects were presented in it in the exhibition entitled ‘Strada Novissima’. It was arranged in the form of a street backdrop whose almost ceiling-high house facades had been built by stagehands from the Cinecittà in Rome according to designs by the invited architects, including Frank Gehry, Oswald Mathias Ungers, Léon Krier, Robert Venturi/John Rauch/Denise Scott Brown and Rem Koolhaas. 8 Cf. La Biennale di Venezia/Carlo Pirovano (ed.), La presenza del passato, Mailand: Electa 1980, esp. 38-48; Robert A. M. Stern, From the past: Strada novisssima, in: Log 20 (2010) 35-38

In particular, these proposals, which returned increased attention to the narrative components in architectural design as well as to historical typological references, together with Rossi’s projects, attracted international attention in the architectural discipline and provoked a broad controversial discussion on postmodern attitudes in architecture. 9 Cf. Paolo Portoghesi, in: id./Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note. 7), 39-41; cf. also Léa-Catherine Szacka, The 1980 Architecture Biennale: The street as a spatial and representational curating device, in: Oase 88 (2012), 14-25 Later, with the ‘Strada Novissima’, this Biennale became landmark and motor of a paradigm shift after the great abstraction of classical modernism. The echo both in everyday architectural practice and in academic research showed far-reaching effects, some of which continue to the present day.

Every Biennale’s artistic director has the privilege of inviting exhibition participants to the Arsenale area and the central Biennale pavilion in the Giardini. He or she conceives the thematic framework and thus provides a starting point for the crystallization of thematic contributions from the perspective of those invited. It is not surprising that in 1996, when national exhibitions were added to the national pavilions for the first time, the Austrian architect Hans Hollein conceived the Biennale exhibition he curated with the theme ‘The Architect as Seismograph’, thus referring to the purpose of the architectural profession to be forward-looking and to sense the future. 10 Cf. Hans Hollein, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 65-71 Some of these first architectural biennials addressed issues of architectural culture such as Islamic architecture (1986) or architectural education in international comparison (1991) and were also accompanied by competitions for projects in the city of Venice such as the reconfiguration of the Rialto Market, a parking garage at Piazzale Roma or the Palazzo del Cinema on the Lido. 11 Cf. Marco de Michelis, Architecture meets Venice, in: Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 29-34

This was followed by biennials, each focussing on current issues in architecture, such as the exhibition ‘Metamorph’ (2004), curated by the theorist Kurt W. Forster, which addressed the broad impact and formative effects of the digital shift in the conception and development of architectural design, especially hybrid projects, or the biennial ‘Cities. Architecture and society’, with which the curator, Richard Burdett (2006), showed the relations of social problems and architectural intervention in the cities of the world with a very large portion of statistics and documentary photographs. 12 Cf. Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 105-125 Both exhibitions highlighted the connection of the worldwide architectural events with technological, political and socio-cultural changes, as well as the necessity of a careful observation of the conditions of the present, in order to contribute to a balanced basis for the development of quality in the discipline.

Since then, the exploration of questions about the foundations of architectural culture has become an increasingly emphasized content of the architecture biennials, for example with the theme ‘People meet in architecture’ for the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale. In her curatorial concept, the Japanese architect Kazuyo Sejima addressed the phenomenon of space as the basic theme of architecture and its specific qualities, as a designed living space as well as a socially formed space. 13 Cf. Hans Ulrich Obrist/Ryue Nishizawa/Kazuyo Sejima, People meet in architecture, in: ids., SANAA, Köln: König 2012, 83-103, esp. 91-94 and 102-102; Kazuyo Sejima, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 166-173 The exhibition project was connected with the intention of reducing the number of contributions and instead increasing their atmospheric intensity. The participants each had a larger area of space at their disposal for independent presentation. Due to this premise, a large number of architectural installations with a strong atmospheric effect were developed especially for this Biennale. In this way, exhibition presentations become an independent design which, distanced from the everyday conditions and tasks of architecture, can take on an artistic character as well as an experimental one. 14 For the experimental character of architecture-based exhibitions cf. Eve Blau, Curating architecture with architecture, in: Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 10-28, esp. 22; critical towards the artistic trait: Carsten Ruhl, Architekturausstellungen. Von der Präsentation zum autonomen Raum der Architektur, in: Wolfgang Sonne (ed.), Die Medien der Architektur, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2011, 303-330, esp. 313 und 330 To think of the appearing link between reflection and action in terms of experimentation can make it possible to observe more deeply the associated potentials for knowledge and epistemological genesis.

Fig. 1: Bernard Tschumi, Advertisements for Architecture Venice Biennale 2012, Photo: Margitta Buchert

Common Ground 2012

With its theme ‘Common Ground’, the Architecture Biennale 2012 virtually called for the exploration, actualization, and generation of a common ‘knowledge space’ of the architectural discipline. The relevance of the influence of the built environment, the continuity of the cultural task, and especially common and shared ideas that form the basis of architectural culture were to be explored, imagined or demonstrated. 15 Cf. David Chipperfield, Preface, in: id./La Biennale di Venezia (ed.), Common Ground. 13th International exhibition of architecture, Venedig: Marsilio 2012, 14-15, here 14; David Chipperfield, Introduction, in: id./Kieran Long/Shumi Bose (eds.), Common Ground: A critical reader, Venice: Marsilio 2012, 13-15 In other words, the architect and curator of this Biennale, David Chipperfield, sketched the outline of a research program in terms of the search for the unknown, the tracing of thesis-like ideas or the exploratory search for and interpretation of principles, coherences or continuities of architecture. With this objective, the Biennale can be characterized in a similar way to how in Western-international contexts research is described – in relation to science and in general. 16 Cf. Chalmers, Alan F., Wege der Wissenschaft. Einführung in die Wissenschaftstheorie, Berlin/Heidelberg/New York 2007, esp. 23-25 and 131-138 It is possible that there are merely incremental differences, occasional deviations, or discipline-specific discursive orders and modes of articulation. With regard to the way of presentation and mediation, and following remarks by Paolo Barratta, president of the Venice Biennale since 2007, it could be asked: Are the exhibitions mere instruments of knowledge, documentations, emotional experiences, or is it precisely the capacity of emotions and imaginations to introduce people to knowledge and to generate knowledge? 17 Cf. Paolo Baratta, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7) 181-195, here 182

David Chipperfield’s desired conceptual orientation of the 2012 Biennale contributions was directed against the currently dominant processes of individualization and separation as well as against the appropriation of architecture by economic, technical, and consumerist forces. 18 Cf. for this and fort he following David Chipperfield, Preface op. cit. (note 15), 14-15 He interpreted the focus ‘common ground’ himself in physical and in intellectual terms, on the one hand as the ground and fundament on which is built and which is collectively shared, as public and ‘civil’ space especially in cities. On the other hand, his intentions were aimed less at individual and autonomous project presentations than at the presentation of reflections and relations, for example, on the link between past and present, on fundamental cross-temporal ideas and research in architecture, or on problem fields in the contemporary world with which architectural production is directly connected. Collective group exhibitions of works of different, but by a common basic attitude connected architecture creators were evoked as well and, by invitation to participate also increasingly intended, architecture-critical contributions.

Fig. 2: David Chipperfield/Kieran Long/Sumi Bose (eds.), Common Ground Cover, Venice: Marsilio 2012, Photo: David Chipperfield Architects

The exhibition was shown in the Giardini, in the buildings and open spaces of the Arsenale, and occasionally in outdoor urban areas of Venice. Presentation media included sketches, graphics, models to mock-ups, material samples, objects, photographs, films, installations, and multimedia. A large number of the presentations had again been created especially for this Biennale. 19 This and the following remarks are based on the author’s participatory observation and documentation. Especially during the opening and closing weeks, there were numerous lecture and discussion events, openings of smaller exhibitions, and many national meetings, as well as the city experience in Venice, through which a distance to the exhibition was created, while at the same time reinforcing the experience and ideas of what this Biennale was supposed to be about. In addition, publications accompanying the exhibition and likewise the worldwide expert and culture journalistic medial dissemination expanded levels of information and understanding.(fig.2) While the exhibition catalog, with its few illustrations and brief descriptions of the individual exhibition projects, remains more documentary in character, the contributions in the additionally published, accompanying volume of essays feature in-depth theoretical reflections on the history and present of various facets of the thematic area of ‘common ground’. They were written by authors from the theory and practice of the architectural discipline as well as from neighboring disciplines such as art, engineering, or sociology, and address, for example, ethical and aesthetic questions of architectural production, buildings and ideas that transcend time, architectural projects, and reflections on their political relevance in conflict regions, on the connection between contemporary architecture and society, or on public and shared areas in the context of architectural and urban spaces.

A large number of people working globally in the field of architecture are addressed and informed by the presence and communication of the exhibition presentations of the Biennale and associated contents. Many of them also come to Venice, meet, communicate, discuss. Space is provided for universities and schools, and guided tours and events are planned. Many Italian and international architecture faculties with students and teachers take up the offer to hold seminars in rooms of the Biennale on the contents presented. According to the Biennale’s president, Paolo Barrata, this clearly shows the character of the Biennale as a place for research and discussion. 20 Paolo Barratta, The exhibition of resonances, in: David Chipperfield/La Biennale di Venezia (eds.), op. cit. (note 15), 12-13, here 13 At the same time, as a public presentation, the Biennale is also visited by a large non-specialist audience, visitors from all over the world as well as from the city of Venice. These exhibition attendances take up a relatively short time span of usually a few days, thereby, naturally, questions are posed about the role of tourism, location policy, and event culture in the production and reception of the biennials and in particular those about the contours of a long-term effect of the contents on architectural discipline.

Examples

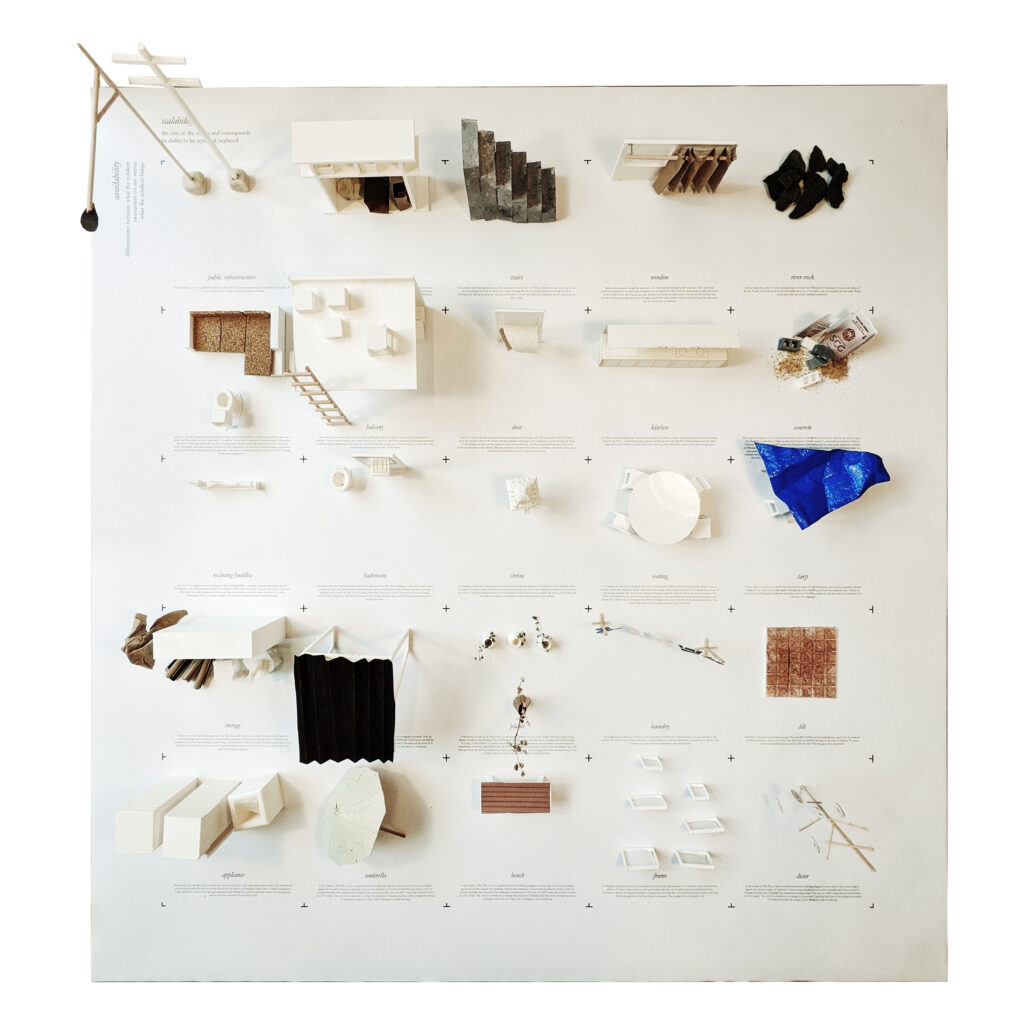

The responses to David Chipperfield’s concept emerged after a preparation period of about 1 year in wide-ranging variations, varying degrees of depth and content. For example, an installation of the Café Gran Horizonte from the unfinished 45-story high-rise tower Torre David in Caracas presented the results of a 12-month investigation by the architects of Urban Think Tank from Venezuela in photographs and films. It was developed in cooperation with journalist Justin McGuirk and photographer Iwan Baan. The research was carried out with the aim of deriving strategies for the future of their own architectural projects from the diverse qualities, comparable to a functioning urban fabric, of the appropriation and conversion of the ruined buildings there by socially underprivileged population groups. 21 Cf. also Urban Think Tank/Torre David/Gran Horizonte, in: David Chipperfield/la Biennale di Venezia (eds.) op. cit. (note 15), 154-155; Justin McGuirk, Gran Horizonte Torre David, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Long/Schumi Bose (eds.), op. cit. (note 15) 275-278 The installation presented by the Italian architect Gino Zucchi ‘Copycat. Empathy and envy as form makers’ was dedicated to an in-depth investigation of recurring forms and their variation in architecture and other areas of life and was presented with photographs, drawings and objects in clusters of metal showcases, for example of souvenir triumphal arches or highrises from different countries, insect shells or architectural working models as well as photographs of Milanese house facades or urban dress codes (fig.3a,b,c). Different dimensions of the relation of typification and morphological basic repertoires to variations and individual interpretation were presented in this way in an insightful and comprehensible way. 22 Cf. Gino Zucchi, Sharing forms: ‘Urbanity’ as emulation and habit, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Long/Schumi Bose, op. cit. (note 15), 113-118

Fig. 3a

Fig. 3b

Fig. 3c: Gino Zucchi, ‘Copycat. Empathy and envy as form makers‘ Installation Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, Photo: Margitta Buchert

Not all contributions showed themselves to be research-led in a comparable intensity, yet many of the other presentations, against the backdrop of the overarching theme of ‘Common Ground’, conveyed the possibility of expanding insights and bodies of knowledge. Another such example is the project ‘Pictographs – Statements of contemporary architects’ initiated by Valerio Olgiati, with which he sought to highlight the multifaceted complex of ‘common ground’ in inspiration and imagination. 23 Cf. for this Valerio Olgiati, The visible origin of architecture, in: id., The images of architects, Luzern: Quart 2013, 3-4 (fig.4) Using a white architectural installation consisting of a panel suspended from the ceiling above a large illuminated table, the architect defined an exhibition setting for the presentation of photographs and pictographs. He had asked 44 architects from around the world to submit depictions with important content and references for them, which act as the basis of their work and which they hold in mind when they design. These were displayed in small glass frames with black borders on the table and showed, for example, photographs of nature by Kazuyo Sejima, African loam architecture and landscapes by David Adjaye or classics of modern architecture by Alberto Campo Baeza, photographs of the reading and sketching architectural icon Mies van der Rohe by Eduardo Souto de Moura, photographs of Aldo Rossi, Joseph Beuys and others role models by Herzog & de Meuron or wallpaper and other pattern cutouts by Jürgen Mayer H.. 24 Cf. Valerio Olgiati, in: La Biennale di Venezia/David Chipperfield (eds.) op. cit. (note 15), 122 As a form of writing with images, Olgiati commented on this exploratory approach. Even if what is presented here remains open to interpretation, it equally contains fundamentals of the history and present of architecture, that for many people, often also for non-professionals, become comprehensible through visualization, just like the reference to nature, reading and reflection, drawing, everyday life practices and people from whom lessons were learned, and exemplary buildings, structures, materials.

Fig. 4: Valerio Olgiati, Pictographs, Installation Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, Photo: Nicolas Saieh

Without requiring extensive commentary, the three architectural sculptures by the Portuguese architects Francisco and Manuel Aires Mateus, Alvaro Siza, and Eduardo Souto de Moura were also presented, in a reduced design, differentiated from one another, and developed and experienced in a site-specific manner in the outdoor space of the Arsenale. 25 Cf. Paolo Barrata, The exhibition of resonances, in: David Chipperfield/La Biennale di Venezia (eds.), op. cit. (note 15), 12-13, here 13 (fig.5) They offered spatial descriptions that made it possible to perceive fundamental aesthetic qualities of architectural space more intensively and, as in the case of Eduardo Souto de Moura’s project, for example, by perceiving the different wall opening configurations as a series of variants presented towards the water area, also to recognize through comparison that quality does not result incidentally and that design practice can also be connected to a researching approach.

Fig. 5: Alvaro Siza, Architecture, Installation Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, Photo: Margitta Buchert

Knowledge Genesis

From the start, the thematic framing ‘Common Ground’ was not fixed to a single stable conception of architecture and thus not to an already clearly contoured segment of knowledge, as is often the case in traditional scientific research. 26 Cf. for this also Philipp Ursprung, Exponierte Experimente. Herzog & de Meurons Modelle, in: Sabine Ammon/Eva Maria Froschauer (eds.) op. cit. (note 2) 289-307, esp. 305 Rather, in the Venice Architecture Biennale, a collectively relevant question of a certain time period receives discipline-specific attention and is subject to comparative and critical discussion.(fig.6) With the respective topic and due to the circumstances of the biennial, contexts arise that thematically separate a segment from the orderlessness of the infinite noise – which has grown exponentially at the latest since the continuous flow of internet information – of current activities and orientations of the architectural discipline. They bring this into a frame and presence that holds ready a potential of knowledge generation and opens up possibilities for orientation and positioning. 27 Cf. Michel Foucault, Die Ordnung des Diskurses. Inauguralvorlesung am Collège de France, 2.12.1970, München: Carl Hanser 1974, 35

Fig. 6: Muck Petzet, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, German Pavilion Venice Architecture Biennale, Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Le_pavillon_de_lAllemagne_(Biennale_darchitecture_de_Venise)_(8085408054).jpg (Commons Wikimedia)

Different levels of knowledge can be found in hybrid forming, as for example in the mixing of everyday knowledge and theoretical knowledge, of knowledge that is related to things, to processes, to people and groups or of subjective and intersubjectively shareable knowledge, of explicit and so-called ‘implicit’ knowledge, to name just a few specifications. 28 Cf. for this also Joan Ernst van Aken, Valid knowledge for the professional design of large and complex design processes, in: Design Studies 26 (2005)/4, 379-404, esp. 487-390; Michel Foucault, Von der Subversion des Wissens, 8th-9th ed. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer 1993, esp. 48-52 Even if individual interpretations have a high degree of subject-specificity, even if knowledge components occur here that can only be vaguely formulated in language, the knowledge generated can act as a resource that can be drawn upon in future processes of action and that allows new contexts to emerge.

Architecture biennials undoubtedly belong to the discursive practices that contribute to the discipline-specific production of knowledge and its habitualized mediation, dissemination, and communication with a global reach. They are characterized by multi-perspective approaches that correspond to heterogeneity of a diverse world. They are not only documenting, rather also generating, are at the same time discourse and field of practice, whose types and characteristics in the context of knowledge genesis and science could only be outlined here. If the research potentials were to be observed reflexively by the participants beyond a historical analysis – and maybe only observed further–, since contents also flow into research and practice, they could make a significant contribution to the visibility of specifically architectural research and also to the differentiation of types of research or fields of research in which design plays a knowledge-generating role. A collective body of knowledge can be expected here, which can have an action-empowering effect, enable structuring and at the same time orientation, which, it could be added, cannot be gained in this way if one’s own practice is only carried on continuously. 29 Cf. also Ryue Nishizawa, in: Hans Ulrich Obrist/id./Kazuyo Sejima, op. cit. (note 13) 92 und 98 The fear, for example expressed by Valerio Olgiati, that architecture will lose its enigmatic effect because nothing will remain untouched and everything will be uncovered and explored, can be set against the span of an immense potentiality that opens up when filters and structurings in a conceptual and experimental free space are also collectively generated and reflected upon in relation to discursive orders of the ‘common ground’. 30 Cf. Valerio Olgiati, op. cit. (note 24), 122; Pier Vittorio Aureli, The common and the production of architecture. Early hypotheses, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Ling/Schumi Bose (eds.), op.cit. (note 15), 147-156, esp. 147-149; furthermore: Michel Foucault, Short cuts, Frankfurt a.M.: Zweitausendeins 2001, 15-16

© Margitta Buchert 2013

Copyright for all images reside with the photographers/holders of the picture rights. The sources and owners of rights are given to the best of our knowledge; please inform us of any we may have omitted.

- Cf. e.g. Michael Gibbons et al., Wissenschaft neu denken. Wissen und Öffentlichkeit im Zeitalter der Ungewissheit, Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft 2005, passim

- Cf. BIRD/Ralf Michel (ed.), Design reserach now! Essays and selected projects, Basel u.a.: Birkhäuser 2007, passim; Sabine Ammon/Eva Maria Froschauer (ed.), Wissenschaft Entwerfen. Vom forschenden Entwerfen zur Entwurfsforschung der Architektur, München: Wilhelm Fink 2013, passim

- Cf. Felicity D. Scott, Operating platforms, in Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 65-69

- Michel Foucault, Die Ordnung der Dinge, 8th ed. Frankfurt a. Main: Suhrkamp 1989, esp. 24-28; Michel Foucault, Archäologie der Wissenschaft, 3rd ed. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1998, esp. 85-87, Andrea Kottmann/Hartmut Rosa/David Strecker, Soziologische Theorien, UTB: Stuttgart 2007, 283

- Cf. e.g. Michel Foucault, AW, op. cit. (note 4), esp. 68-74

- Cf. Hannelore Bublitz, Diskurs, Bielefeld: Transcript 2002, esp. 56-60

- For this and for the following cf. Aaron Levy/William Menking, Architecture on display. On the history of the Venice Biennale of Architecture, London: Architectural Association 2010, from 12 and passim

- Cf. La Biennale di Venezia/Carlo Pirovano (ed.), La presenza del passato, Mailand: Electa 1980, esp. 38-48; Robert A. M. Stern, From the past: Strada novisssima, in: Log 20 (2010) 35-38

- Cf. Paolo Portoghesi, in: id./Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note. 7), 39-41; cf. also Léa-Catherine Szacka, The 1980 Architecture Biennale: The street as a spatial and representational curating device, in: Oase 88 (2012), 14-25

- Cf. Hans Hollein, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 65-71

- Cf. Marco de Michelis, Architecture meets Venice, in: Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 29-34

- Cf. Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 105-125

- Cf. Hans Ulrich Obrist/Ryue Nishizawa/Kazuyo Sejima, People meet in architecture, in: ids., SANAA, Köln: König 2012, 83-103, esp. 91-94 and 102-102; Kazuyo Sejima, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7), 166-173

- For the experimental character of architecture-based exhibitions cf. Eve Blau, Curating architecture with architecture, in: Log: Observations on architecture and the contemporary city 20 (2010) 10-28, esp. 22; critical towards the artistic trait: Carsten Ruhl, Architekturausstellungen. Von der Präsentation zum autonomen Raum der Architektur, in: Wolfgang Sonne (ed.), Die Medien der Architektur, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag 2011, 303-330, esp. 313 und 330

- Cf. David Chipperfield, Preface, in: id./La Biennale di Venezia (ed.), Common Ground. 13th International exhibition of architecture, Venedig: Marsilio 2012, 14-15, here 14; David Chipperfield, Introduction, in: id./Kieran Long/Shumi Bose (eds.), Common Ground: A critical reader, Venice: Marsilio 2012, 13-15

- Cf. Chalmers, Alan F., Wege der Wissenschaft. Einführung in die Wissenschaftstheorie, Berlin/Heidelberg/New York 2007, esp. 23-25 and 131-138

- Cf. Paolo Baratta, in: Aaron Levy/William Menking, op. cit. (note 7) 181-195, here 182

- Cf. for this and fort he following David Chipperfield, Preface op. cit. (note 15), 14-15

- This and the following remarks are based on the author’s participatory observation and documentation.

- Paolo Barratta, The exhibition of resonances, in: David Chipperfield/La Biennale di Venezia (eds.), op. cit. (note 15), 12-13, here 13

- Cf. also Urban Think Tank/Torre David/Gran Horizonte, in: David Chipperfield/la Biennale di Venezia (eds.) op. cit. (note 15), 154-155; Justin McGuirk, Gran Horizonte Torre David, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Long/Schumi Bose (eds.), op. cit. (note 15) 275-278

- Cf. Gino Zucchi, Sharing forms: ‘Urbanity’ as emulation and habit, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Long/Schumi Bose, op. cit. (note 15), 113-118

- Cf. for this Valerio Olgiati, The visible origin of architecture, in: id., The images of architects, Luzern: Quart 2013, 3-4

- Cf. Valerio Olgiati, in: La Biennale di Venezia/David Chipperfield (eds.) op. cit. (note 15), 122

- Cf. Paolo Barrata, The exhibition of resonances, in: David Chipperfield/La Biennale di Venezia (eds.), op. cit. (note 15), 12-13, here 13

- Cf. for this also Philipp Ursprung, Exponierte Experimente. Herzog & de Meurons Modelle, in: Sabine Ammon/Eva Maria Froschauer (eds.) op. cit. (note 2) 289-307, esp. 305

- Cf. Michel Foucault, Die Ordnung des Diskurses. Inauguralvorlesung am Collège de France, 2.12.1970, München: Carl Hanser 1974, 35

- Cf. for this also Joan Ernst van Aken, Valid knowledge for the professional design of large and complex design processes, in: Design Studies 26 (2005)/4, 379-404, esp. 487-390; Michel Foucault, Von der Subversion des Wissens, 8th-9th ed. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer 1993, esp. 48-52

- Cf. also Ryue Nishizawa, in: Hans Ulrich Obrist/id./Kazuyo Sejima, op. cit. (note 13) 92 und 98

- Cf. Valerio Olgiati, op. cit. (note 24), 122; Pier Vittorio Aureli, The common and the production of architecture. Early hypotheses, in: David Chipperfield/Kieran Ling/Schumi Bose (eds.), op.cit. (note 15), 147-156, esp. 147-149; furthermore: Michel Foucault, Short cuts, Frankfurt a.M.: Zweitausendeins 2001, 15-16