Return to archive

title

Rooms: Architectural Model-Making as Ethnographic Research

author

Ecaterina Stefanescu

Abstract

Within design and architecture, scale models can create worlds of proposition, speculation and fiction. This paper situates the model as a tool for observation, documentation and engagement; a slow, durational method that manifests a deep participation in the lives of place and people marginalised by wider society. Rooms was an artistic and research project undertaken as part of the Urban Nation artistic residency in Berlin which looked at the Romanian immigrant community inhabiting the city, the spaces they occupy and appropriate, and the objects that they surround themselves with. These instances were drawn, surveyed, documented and then recreated through 1:20 paper models. Built to an extreme level of detail the models of everyday space visualise, offer new insight, and give a sense of value and recognition to the lived realities of individuals. A situated mode of research, this form of representation transforms the seemingly mundane into an object of beauty and atmosphere, encouraging access and participation from the participant, maker and the viewer. The inherently collaborative aspect of this process reveals the tacit, implicit knowledge present in everyday actions.

Introduction

Within architecture, models play roles of proposition, speculation, and fiction. This paper situates the model as a means of observation, documentation, and engagement with marginalised and migrant communities. It investigates how studying the material culture of migrants through the medium of Ethnographic Model-Making showcases and validates the migrant’s liminal condition, and how acts of making add to community engagement practice. The paper will outline how models, as material vectors, move the conversation further, negotiating between the different actors involved in participatory art and community engagement: the participants, the maker(s), and the public.

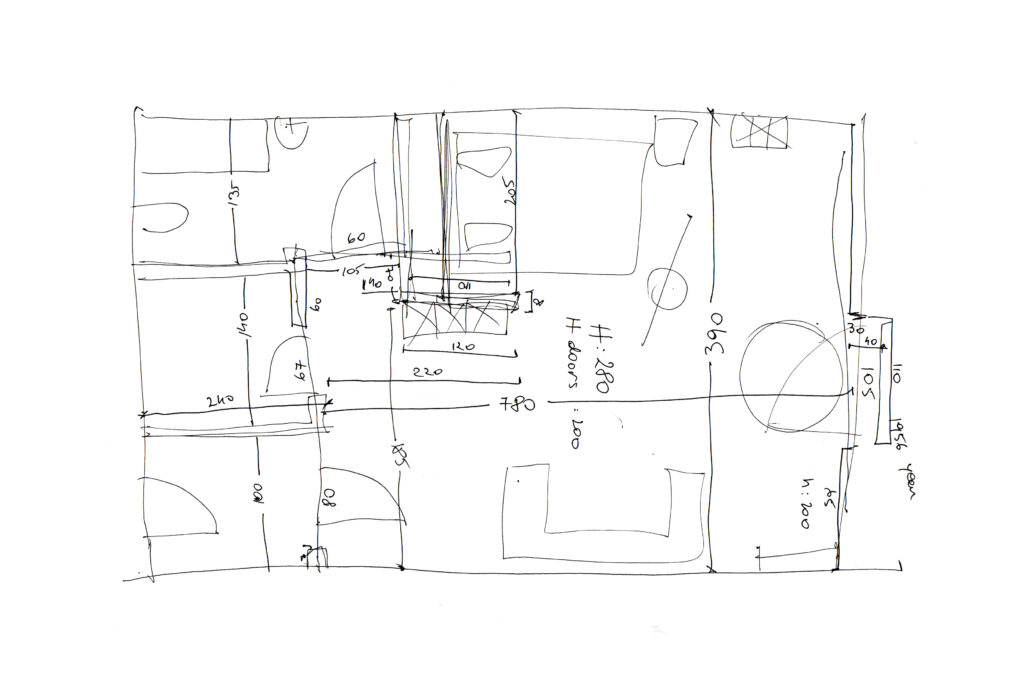

Fig. 1

This research explores Rooms, an artistic project examining the Romanian migrant community in Berlin through the spaces they occupy and the objects with which they surround themselves. The case studies – a Romanian shop and two domestic spaces – were documented, drawn, surveyed, and carefully recreated through 1:20 paper models (figure 1).

1

This research has been undertaken as part of the Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art – “Fresh AIR” artistic residency in Berlin between October 2021 and March 2022. The residency, titled “Reflecting Migration”, was intended to replace common stereotypical portrayals of migrants. The final artistic outputs included three models of Romanian immigrant spaces and a series of collages which were exhibited as part of a group show at the Bülow90 Gallery in Berlin between March and July 2022. See Fresh A.I.R. #6 Exhibition of the Artists in Residence „Reflecting Migration “(2022), Stiftung Berliner Leben <https://www.stiftung-berliner-leben.de/fresh-a-i-r-6-exhibition-of-the-artists-in-residence/> [accessed 16 October 2022].

For migrants, the nostalgic association with native objects and places helps to build identity. But it can also create a more complex condition, where an inner, intangible border is created that seeks to protect the migrant from the loss inherent in their displacement. Modelling their everyday spaces gives a sense of value and recognition to the lived realities of individuals and communities often ignored and marginalised, revealing this complex inner predicament. The models draw attention to their everyday spaces, showing them as objects of beauty and atmosphere through the dedication required to realise this form of three-dimensional representation.

Ethnographic Model-Making is a methodology which reveals the tacit knowledge existent within communities that often gets lost or mis-appropriated through conventional community consultation exercises and data collection.

Migrancy

Researching the experience of diasporic communities, Andreea Deciu Ritivoi writes about the conundrum that immigrants face when arriving in a new country. They are forced to change their way of being to adapt and integrate into a host society and culture, but this adjustment is often experienced as a kind of ‘loss’.

2

Andreea Deciu Ritivoi, Yesterday’s Self: Nostalgia and the Immigrant Identity (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), 1.

According to Ritivoi, feelings of nostalgia are a marker of the journey for the migrant, and ‘a defensive mechanism designed to maintain a stable identity’ in the face of this inevitable loss.

3

Ritivoi, 9.

Material objects emerge as symbols of stability for migrants, when personal uncertainty occurs as their surroundings change or move.

4

Maurice Halbwachs, The Collective Memory, trans. by Francis J. Ditter, Jr. and Vida Yazdi Ditter (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 129.

Sociologist Maurice Halbachs identifies domestic spaces occupied by an individual as bearing the inhabitant’s imprint, through furniture, decorations, and objects.

5

Halbachs, 128-129.

By clinging to objects that trigger nostalgia, individuals long for a sense of stability.

Ritivoi further describes that an individual’s identity is dependent on their environment, so migrants seek to recreate their habitat in the image of their place of origin and their inner self.

6

Ritivoi, 8.

By re-establishing the world of home in their new surroundings – through bringing objects of nostalgia, buying produce imported from their country of origin in traditional shops and preparing national food – they attempt to halt the inevitable change and loss, and transform their new surroundings into the places for which they long.

As an immigrant myself, I have experienced this transient position and sense of loss. I was born and grew up in Romania, but I have been living abroad for 12 years, and have a complex and hard to define relationship with my country of origin. Moving around so much meant that it was very difficult to carry many personal objects with me, so the way I maintained my connection to my country was through foods and drinks, searching for Romanian shops everywhere I would go to get a taste of back home.

The foreign grocery store is at the centre of a city’s scattered diaspora. As immigrants now tend to live more dispersed in a city, the shop is at the heart of their immigrant experience, as the place where they can meet each other, network, and get produce from their country of origin. Visually, the foreign commercial unit is often a mystery to most passers-by, with non-native language signs and shop windows plastered with posters and produce leaflets.

Along with the selling of Romanian produce, meats, drinks, sweets and other groceries to the large diaspora from the area, the shop is also a place where the Romanian language is spoken freely, and where the jokes, opinions and conversations are understood by all, rendering it an important social hub.

Through its design, opening and existence, the Romanian Shop constitutes a “spatial production of locality”.

7

Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 180.

With the addition of a temporal dimension through the introduction of ‘rituals’ – in this case, the quotidian action of doing one’s grocery shopping and spending time with fellow Romanians – the nature of this spatial practice and the social performance that comes with it is what creates the notion of locality and social cohesion for the community members.

For the Romanian diaspora, the re-design of generic commercial units with the Romanian tricolour of Blue, Yellow and Red is an act of what Ela Kacel called “self-localization” in a newly appropriated place.

8

In the case study further elaborated on within this paper, a former branch of now defunct German drugstore company Schlecker located on the corner of a building in Friedenau, became a Romanian shop.

Taking cues from Halbachs, she describes how migrants create locality by giving meaning to places, which in turn take on a new liminal identity, and gives the example of the foreign grocery store that is a bridge between the host and the origin country.

9

Ela Kaçel, “Self-Localization of Migrants and Photographers in Cities via Self-Images,” Candide. Journal for Architectural Knowledge 12 (2021), 119–136, here 122.

The store has the potential to become a new place for the collective memory of migrants as the shopping experience is compounded by the nostalgic element of the items on sale and the relationships that develop with fellow nationals. In the same way in which emotional association is to be found at the scale of the object, at the urban scale, the shop is not only the main commercial hub for the Romanian diaspora in the city, but also acts as the repository for the preservation and consumption of memory.

Ethnographic research

To study and document these everyday spaces and observe the rituals associated with them, the project applied an ethnographic research approach, which included situated actions of visiting and engaging with these places. I took part in the acts of consumption taking place, meeting and conversing with the owners and employees as well as regular customers.

Fig. 2

To take engagement with the community and its spaces even further however, architect Lee Ivett advocates for a performative act of making, which allows the artist to register not only the physical material environment, but also the behaviour within that environment through public, in-situ making. 10 As he writes, by “participating in many aspects of a place through the act of making”, local insight is gained through first-hand experience. Through his work with(in) marginalised communities in Glasgow, Lee Ivett designed and led on projects which focus on the act of making as a participatory activity that has the potential to gather meaningful data and impact directly on a place. “I am from Reykjavik”, an artistic project by Sonia Hughes for which Ivett co-designed the structure and the artistic act, tests the methodology of making as performance in a public space. See Lee Ivettt, The Act of Making as Participation and Enquiry (2021), I am from Reykjavik <https://www.iamfromreykjavik.com/portfolio-item/the-act-of-making/> [accessed 16 October 2022]. In Rooms, although the act of creation was a one-sided activity, it allowed me to occupy and embed myself in the spaces. Through this situated mode of practice, the activities and rituals of the people working or using the shop slowly reveal themselves, and the importance of the Shop not only as a commercial amenity, but as a social and meeting hub for the Romanian diaspora becomes apparent.

Fig. 3

The visual methods I used included site sketching, drawing and spatial surveying as durational ways through which I not only observed and documented the spaces in two dimensions, but which were also the catalyst for further conversations and informal interviews with project participants (figure 2). In one particular Romanian Shop, I met a young woman working there, and a pensioner frequenting the shop to socialise with other Romanians. Over a period of a few months, their interest in the project grew, allowing me to gain trust and access, into their spaces and into their lived realities (figure 3).

11

Both participants were forthcoming and interested in the research, allowing me to gain access. No names or addresses were to be used within the academic dissemination of the project, and a verbal agreement was made to document their spaces and some of their personal objects.

The value of “visual research methods” as described by Gillian Rose lie not only in their potential ease of dissemination, but also in producing insight that simple interviews, for example, cannot. Furthermore, by concentrating on the ordinary and the mundane, valuable but otherwise overlooked experiences are revealed in everyday actions.

12

Gillian Rose, “On the relation between ‘visual research methods’ and contemporary visual culture”, The Sociological Review, Vol. 62, 24–46 (2014) DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.12109,24-46, here 27-28.

The acquisition of tacit knowledge through the process of making is a known method utilised in ethnographic and anthropological research.

13

Ralf Liptau,”R is for Representation”, in Olivia Horsfall Turner et al., eds., An Alphabet of Architectural Models, (London: Merrell, 2021), 82-84.

Through the act of making, anthropologist Tim Ingold argues that the researcher at once exists as observer and participant, and there is no differentiation between implicit knowledge and told, articulated knowledge when the observation does not take the form of data collection.

14

Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (London: Routledge, 2013), 5.

Through practice and experience the transfer of knowledge between the different actors involved in this process takes place, and the Maker, through the model/vector, simultaneously observes, documents and analyses.

15

Ingold, 109.

Models

Fig. 4

The reproduction of the spaces three-dimensionally constituted a formal analysis: through physically re-making the commercial, and later, the domestic interiors, I was forced to re-inhabit the spaces, and embed myself in the lives of the people whose spaces I was depicting (Figure 4). By manually constructing the interiors and all the items within, the level of insight amassed about the rooms and their inhabitants could not be replicated by simply observing or documenting the spaces in two dimensions. Richard Sennet talks about the “evolutionary dialogue between the hand and the brain”.

16

Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London: Penguin, 2009), 151.

He writes that the information received though the hands is richer, more sensate than through the eye, and argues for the tacit knowledge created by “hand habits”.

17

Sennet, 10.

The haptic and participatory benefit of models, together with their didactic potential, has been utilised in the on-going artistic and research project “The Giant Doll’s House” run by Catja de Haas Architects.

18

Started in 2014, the social arts project asked participants to create models of their past, present or imaginary homes within the confines of a shoebox. The international project involved people from different backgrounds, including schoolchildren, community members and refugees, aiming to raise awareness about the importance of home and utilising the act of making to explore ‘ideas of identity, both shared as well as personal’. About the Giant Dolls’ House Project ([n.d.]), The Giant Dolls’ House Project <https://giantdollshouse.org/about> [accessed 8 January 2023].

The project quotes Gaston Bachelard, who talks about the condensing of value within miniatures. Bachelard suggests that the scaled-down version of the object is richer and more packed with insight than the real object, and by creating something small and gazing upon it, one generated insight and understanding that would not be possible by simply studying the real thing.

19

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. by Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 150.

But more so than this, the miniature increases the importance and value of the object being depicted, revealing it as a ‘refuge of greatness’.

20

Bachelard, 155.

The care and attention employed in the making of the miniatures for Rooms implies an engagement that goes beyond the ordinary, therefore emphasising their importance. As opposed to two-dimensional representations of spaces, the model allows participants and viewers to examine, think about and imagine more readily the volume, objects, light and atmosphere of a place; “models have a “hereness” that makes structures they describe tangible, present bodies”.

21

Matthew Mindrup, The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, The Exemplar and the Muse (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 2019), 2.

The realism of representation, in this case, adds to the sensory nature of the research. Through the extreme level of detail, external observers and the public are encouraged to occupy and embed themselves in what Sarah Pink terms ‘the ethnographic place’ of the model. By viewing it from multiple directions, it forces an empathetic response that draws attention to the importance, worth and draw of these quotidian spaces for their users.

22

Sarah Pink, Doing Sensory Ethnography, (Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing, 2009), 42.

This form of representation reveals the simple, ordinary spaces as objects of beauty and enchantment.

Rooms also uses the act of making to explore ideas of identity. The models of the migrant interiors are not only physical representations of the spaces and objects within, but also of the complicated, liminal identities of their inhabitants. The focus on recreating the mundane minutiae renders this liminal condition tangible, revealing the value that migrants place on objects and artefacts that help them maintain a connection to back home (figure 5).

Fig. 5

Using architectural models as participatory tools in conducting visual ethnographic research has been tested in a study as part of a design research looking at domestic spaces in the UK. 23 The project and paper argued that architecture models are appropriate “visual probes” within participatory events to advance design research and enquiry, in this case, between material possessions and housing design. But whereas Marco et al. produce an abstracted, analytical model as part of their process, the models for Rooms have been produced in such a way as to render them as objects of art, immediately recognisable through the care and attention given to every detail. Elena Marco et al., “The Architectural Model as Augmenting a Sensory Ethnography”, The Design Journal, 24:6, 843-864,(2021), DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2021.1949237, 846. Similarly testing the model as a visual probe, I brought one of the domestic models back to the Romanian Shop where I initially met the project participants, and observed the reactions towards it: from the apartment’s owner, to friends who have visited the real space, and complete strangers. As the reactions varied, there was no doubt that even a small experiment such as this could generate a huge and important amount of insight. 24 The event took place in October 2022, after the closing of the exhibition. Only in the space for a limited amount of time during the day, the model was then taken back to the owner’s apartment and became of treasured artistic possession.

The Model as Vector

Planning, programming, and untangling tacit knowledge is inherently a difficult and messy undertaking. Working within a community using ethnographic methodologies of researching and creating means there were no set preconceptions and only vague expectations of outputs. The approach and method of study and production for Rooms embraced this messiness of generating and disseminating instinctive observations and understanding. The spatial model appeared as the most appropriate way to engage with the liminal interiors and belongings of migrants and the complex lives and moments playing within, as the vector through which not only is the knowledge gained and spread, but these lives are elevated.

Conclusion

Experiencing a sense of loss through the change in their surroundings, migrants seek to replicate the nostalgic past through everyday objects and spaces that speak not only of their place of origin, but also of their identity. The culture of origin, representing the longed-for realm of their nostalgic past, is projected unto the quotidian of the host culture through material possessions. But in a foreign context, this produces a liminal identity when the culture of origin, recalled through nostalgic associations with objects and physical artefacts, is juxtaposed unto new surroundings.

Rooms demonstrates the use and appropriateness of a novel Ethnographic Model-Making methodology. By miniaturising the contested, transitory immigrant space, the maker comes to understand the space and the objects intimately, and by hand-making the art-object, gets to participate in the lives of the individuals and the community depicted.

The models become the device through which the community’s experiences are told. Modelling migrant spaces not only produces a visual representation of the places, but also explores the liminal identity of migrants on a deeper level. The models become objects of atmosphere and beauty, which recognise, acknowledge, and bring value to the feelings experienced by the community and their lived reality within this transitory condition.

Bibliography

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

About the Giant Dolls’ House Project ([n.d.]), The Giant Dolls’ House Project <https://giantdollshouse.org/about> [accessed 8 January 2023].

About Us ([n.d.]), Revoelution <https://www.revoelution.org.uk/about> [accessed 26 February 2023].

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space, translated by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1994.

Fresh A.I.R. #6 Exhibition of the Artists in Residence „Reflecting Migration“(2022), Stiftung Berliner Leben<https://www.stiftung-berliner-leben.de/fresh-a-i-r-6-exhibition-of-the-artists-in-residence/> [accessed 16 October 2022].

Halbwachs, Maurice. The Collective Memory, translated by Francis J. Ditter, Jr. and Vida Yazdi Ditter. New York: Harper & Row, 1980.

Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge, 2013.

Ivett, Lee. The Act of Making as Participation and Enquiry (2021), I am from Reykjavik<https://www.iamfromreykjavik.com/portfolio-item/the-act-of-making/> [accessed 16 October 2022].

Kaçel, Ela. “Self-Localization of Migrants and Photographers in Cities via Self-Images,” Candide. Journal for Architectural Knowledge 12 (2021): 119–136.

Liptau, Ralf. ”R is for Representation”. In An Alphabet of Architectural Models, edited by Olivia Horsfall Turner, Simona Valeriani, Matthew Wells and Teresa Fankhanel, 82-84. London: Merrell, 2021.

Marco, Elena, Williams, Katie, Oliveira, Sonja, Sinnett, Danielle. “The Architectural Model as Augmenting a Sensory Ethnography”. The Design Journal, 24:6, (2021): 843-864. DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2021.1949237.

Mindrup, Matthew. The Architectural Model: Histories Of The Miniature And The Prototype, The Exemplar And The Muse, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019)

Pink, Sarah. Doing Sensory Ethnography. Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing, 2009.

Ritivoi, Andreea Deciu. Yesterday’s Self: Nostalgia and the Immigrant Identity. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002.

Rose, Gillian. “On the relation between ‘visual research methods’ and contemporary visual culture”, The Sociological Review, Vol. 62, 24–46, (2014): 24-46. DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

Sennett, Richard. The Craftsman. London: Penguin, 2009.

- This research has been undertaken as part of the Urban Nation Museum for Urban Contemporary Art – “Fresh AIR” artistic residency in Berlin between October 2021 and March 2022. The residency, titled “Reflecting Migration”, was intended to replace common stereotypical portrayals of migrants. The final artistic outputs included three models of Romanian immigrant spaces and a series of collages which were exhibited as part of a group show at the Bülow90 Gallery in Berlin between March and July 2022. See Fresh A.I.R. #6 Exhibition of the Artists in Residence „Reflecting Migration “(2022), Stiftung Berliner Leben <https://www.stiftung-berliner-leben.de/fresh-a-i-r-6-exhibition-of-the-artists-in-residence/> [accessed 16 October 2022].

- Andreea Deciu Ritivoi, Yesterday’s Self: Nostalgia and the Immigrant Identity (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), 1.

- Ritivoi, 9.

- Maurice Halbwachs, The Collective Memory, trans. by Francis J. Ditter, Jr. and Vida Yazdi Ditter (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 129.

- Halbachs, 128-129.

- Ritivoi, 8.

- Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 180.

- In the case study further elaborated on within this paper, a former branch of now defunct German drugstore company Schlecker located on the corner of a building in Friedenau, became a Romanian shop.

- Ela Kaçel, “Self-Localization of Migrants and Photographers in Cities via Self-Images,” Candide. Journal for Architectural Knowledge 12 (2021), 119–136, here 122.

- As he writes, by “participating in many aspects of a place through the act of making”, local insight is gained through first-hand experience. Through his work with(in) marginalised communities in Glasgow, Lee Ivett designed and led on projects which focus on the act of making as a participatory activity that has the potential to gather meaningful data and impact directly on a place. “I am from Reykjavik”, an artistic project by Sonia Hughes for which Ivett co-designed the structure and the artistic act, tests the methodology of making as performance in a public space. See Lee Ivettt, The Act of Making as Participation and Enquiry (2021), I am from Reykjavik <https://www.iamfromreykjavik.com/portfolio-item/the-act-of-making/> [accessed 16 October 2022].

- Both participants were forthcoming and interested in the research, allowing me to gain access. No names or addresses were to be used within the academic dissemination of the project, and a verbal agreement was made to document their spaces and some of their personal objects.

- Gillian Rose, “On the relation between ‘visual research methods’ and contemporary visual culture”, The Sociological Review, Vol. 62, 24–46 (2014) DOI: 10.1111/1467-954X.12109,24-46, here 27-28.

- Ralf Liptau,”R is for Representation”, in Olivia Horsfall Turner et al., eds., An Alphabet of Architectural Models, (London: Merrell, 2021), 82-84.

- Tim Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture (London: Routledge, 2013), 5.

- Ingold, 109.

- Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London: Penguin, 2009), 151.

- Sennet, 10.

- Started in 2014, the social arts project asked participants to create models of their past, present or imaginary homes within the confines of a shoebox. The international project involved people from different backgrounds, including schoolchildren, community members and refugees, aiming to raise awareness about the importance of home and utilising the act of making to explore ‘ideas of identity, both shared as well as personal’. About the Giant Dolls’ House Project ([n.d.]), The Giant Dolls’ House Project <https://giantdollshouse.org/about> [accessed 8 January 2023].

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. by Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 150.

- Bachelard, 155.

- Matthew Mindrup, The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, The Exemplar and the Muse (Cambridge: the MIT Press, 2019), 2.

- Sarah Pink, Doing Sensory Ethnography, (Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing, 2009), 42.

- The project and paper argued that architecture models are appropriate “visual probes” within participatory events to advance design research and enquiry, in this case, between material possessions and housing design. But whereas Marco et al. produce an abstracted, analytical model as part of their process, the models for Rooms have been produced in such a way as to render them as objects of art, immediately recognisable through the care and attention given to every detail. Elena Marco et al., “The Architectural Model as Augmenting a Sensory Ethnography”, The Design Journal, 24:6, 843-864,(2021), DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2021.1949237, 846.

- The event took place in October 2022, after the closing of the exhibition. Only in the space for a limited amount of time during the day, the model was then taken back to the owner’s apartment and became of treasured artistic possession.