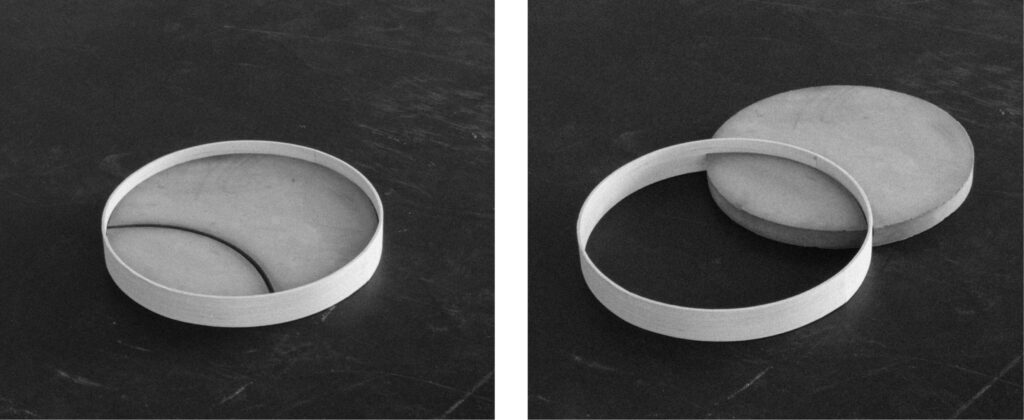

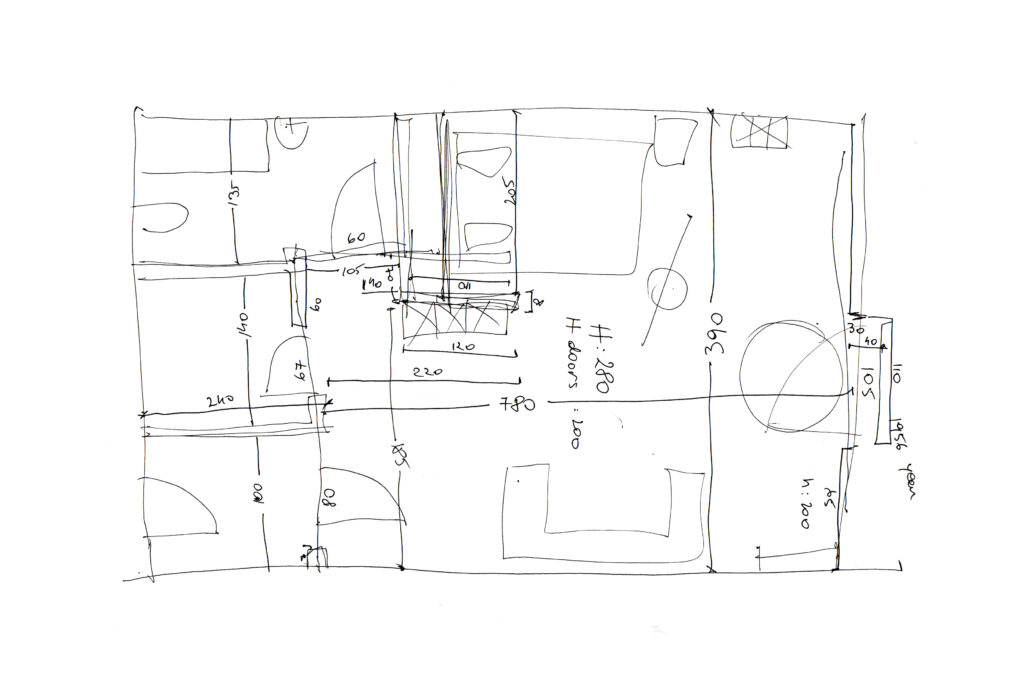

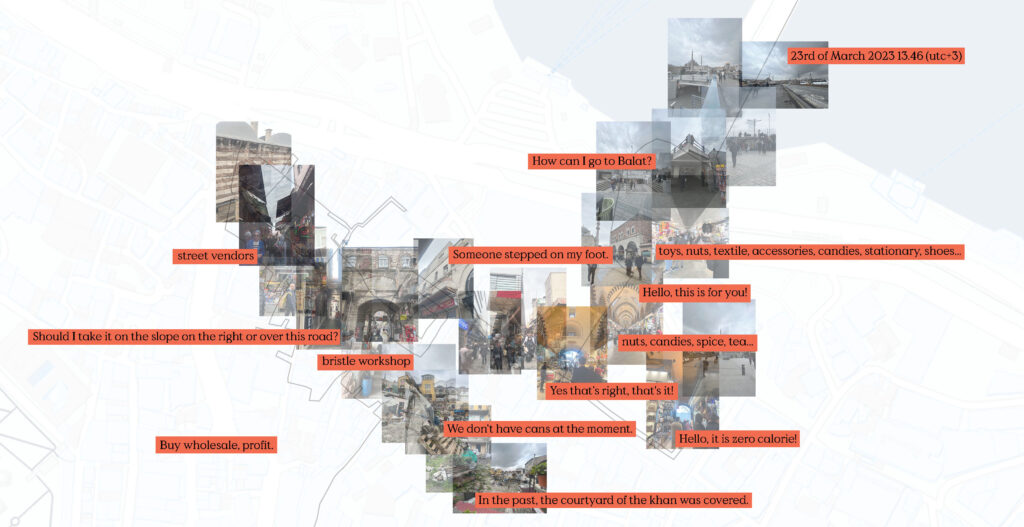

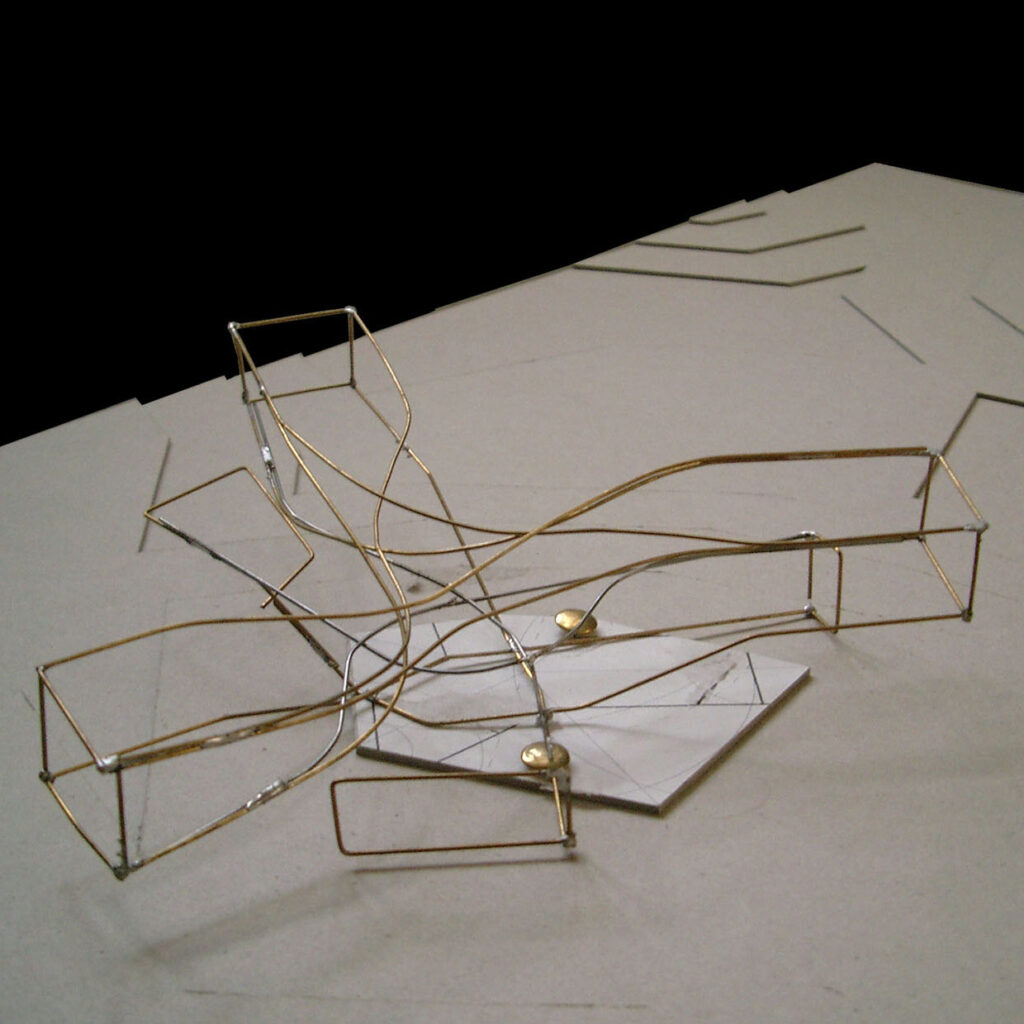

Herman Hertzberger, Sketch Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid, The Hague, The Netherlands, August 1984

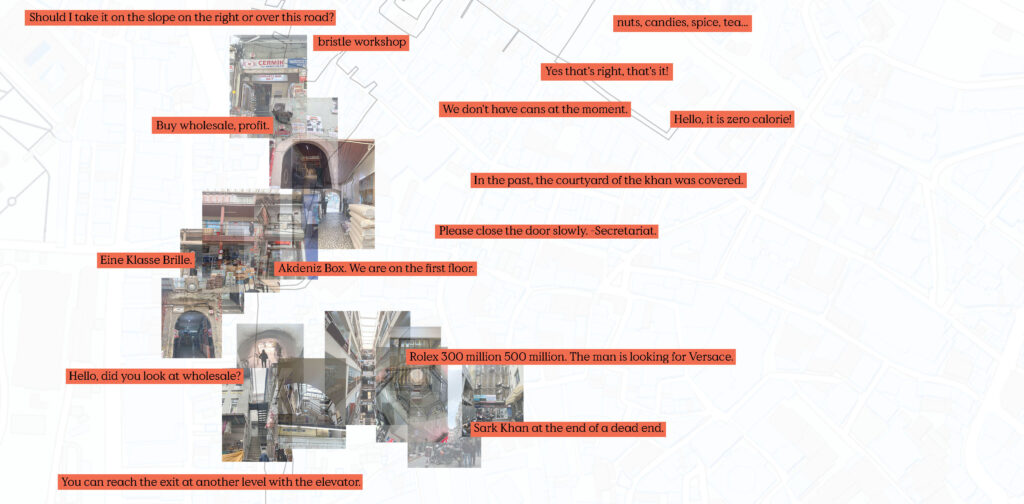

‘I, of course, don’t want to come across as a plodder!’ the Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger said. Together with architectural historian Herman van Bergeijk, to whom I was a student assistant, I visited him in his office in Amsterdam on a cold Winter Day in the early 2000s. Van Bergeijk, together with Deborah Hauptmann, had published a nice booklet presenting and discussing Hertzberger’s sketches from his notebooks, and aimed to propose a subsequent book, now focusing on another means of design, the vast amount of A3 chalk paper sketches produced by the architect.

While the notebooks offer him the opportunity to quickly note, draw and test ideas during meetings or on the go, the A3 papers are amongst his instruments while working in the office. Their size requires space, a desk, and a certain concentration. They allow him to sketch out certain ideas on a larger scale, as well as easily withdraw them, adjusting little details.

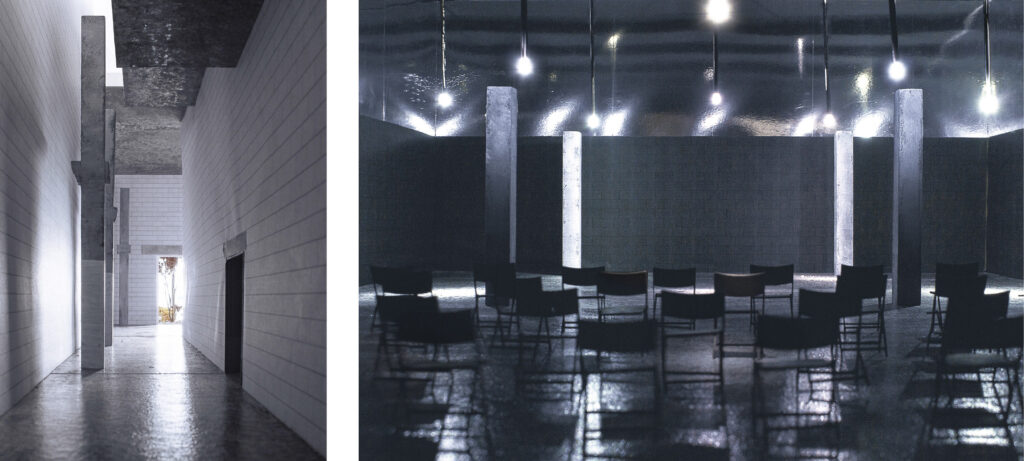

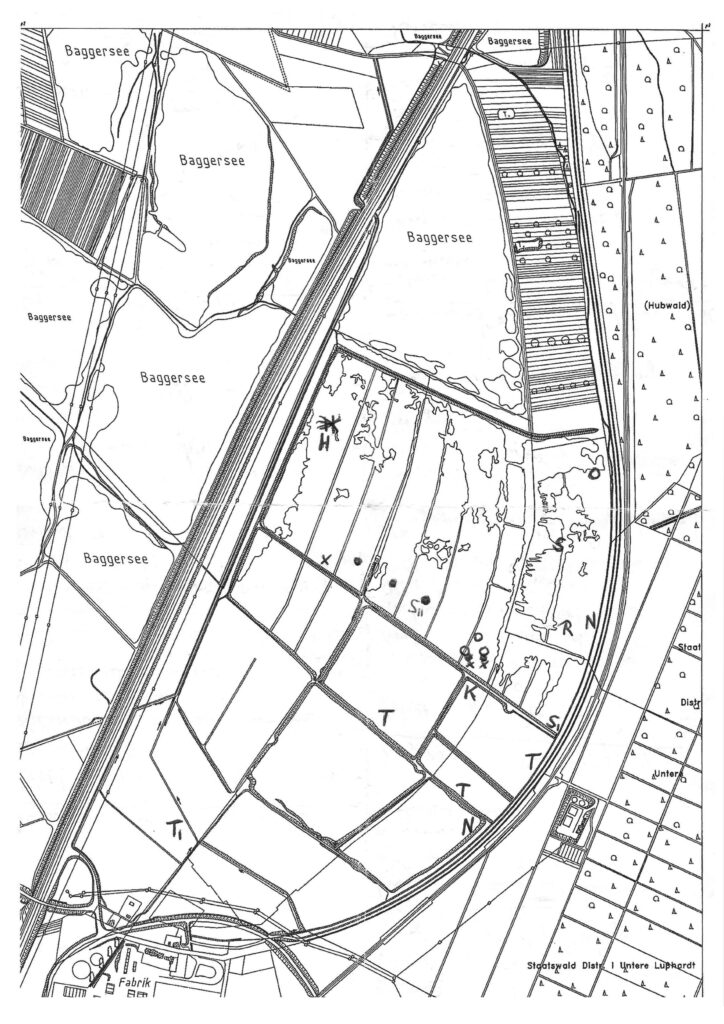

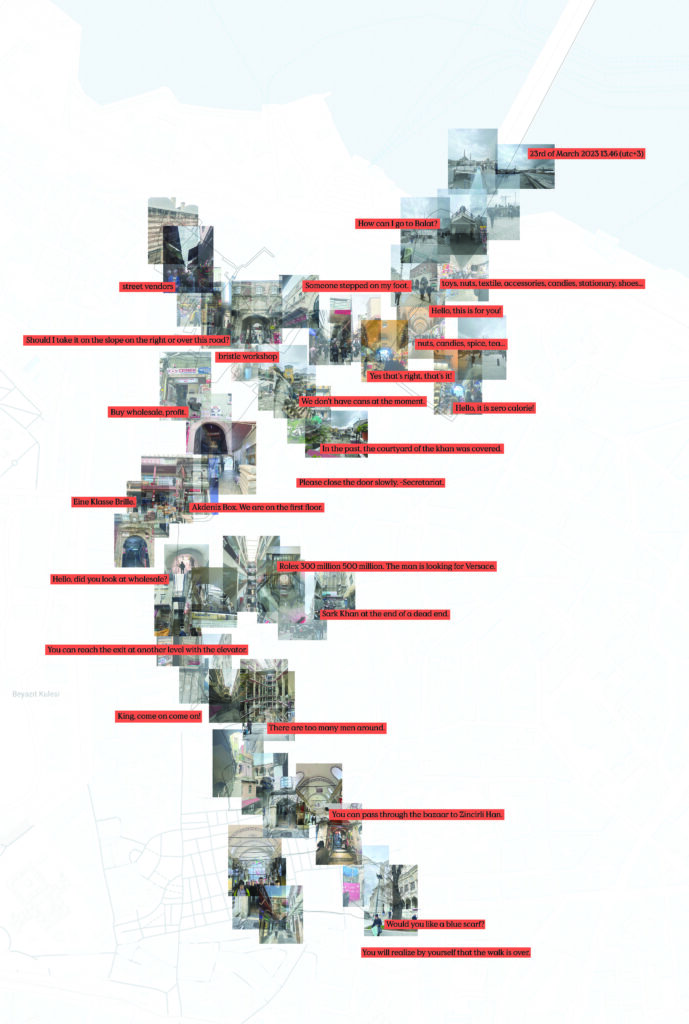

While proposing this idea for the new book, Hertzberger hesitated. Would it not picture him as a plodder? He nevertheless gave Van Bergeijk and myself permission to have a first look in the archive and to explore a few series of his sketches. Scrolling through his sketches, they already revealed a first glimpse of Hertzberger’s method of designing. He works systematically, always on the same A3 chalk paper and mostly with pencil. Sometimes he articulates the contours with black fineliner. Sometimes he draws out a perspective on the whole size of the paper, but mostly, the sheet of paper is full of small scribbles, exploring a single idea in different variations. Often an idea is drawn several times – which is why the chalk paper is important: it is easy to trace over from a previous drawing, to change just a few details. Exploring the sketches, one sees the development from the research of the site, first ideas for the building, the testing of several variants, detours, even strays, to a final idea, which has to be picked up again after a good night sleep, a discussion with to employees in the office, the design being presented to the client, after a conversation with a constructor, or how otherwise new information affects the possibilities.

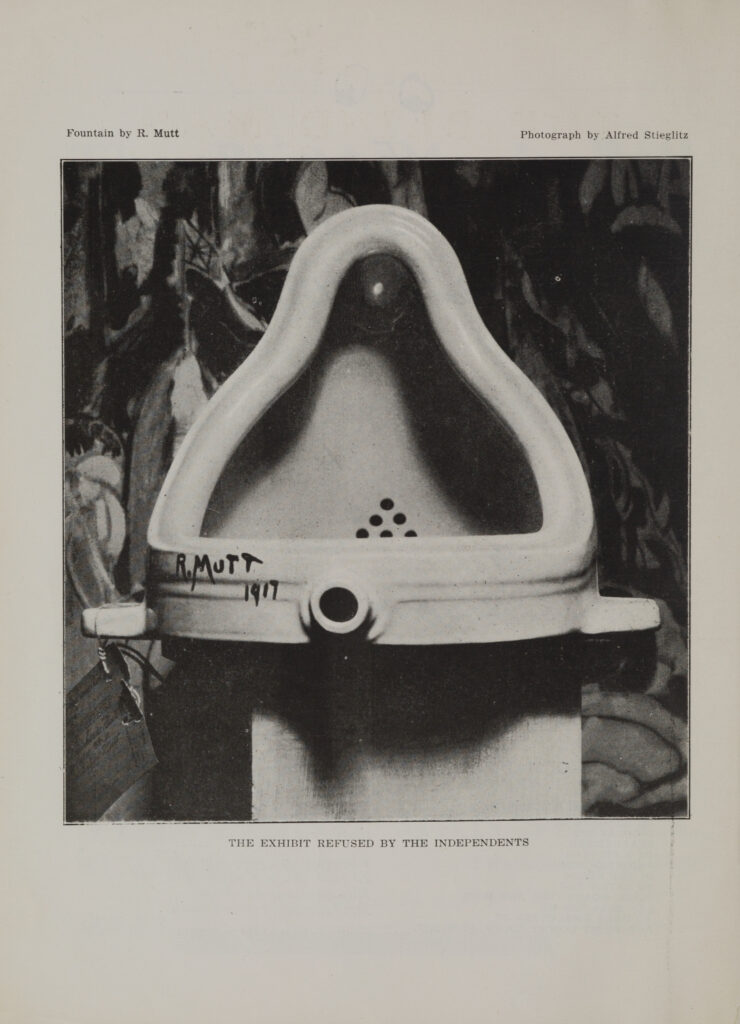

Not that Hertzberger hid these sketches from the public eye. He showed any of them in his lectures for students and published them in his books, or otherwise presented them in exhibitions. But to collect and present the whole series made him hesitate. Wouldn’t it earn him the image of a plodder? His concern is understandable against the backdrop of Dutch architecture culture at the time, where, in the wake of OMA, firms like MVRDV were gaining worldwide fame with their conceptual architecture. A strong concept, a singular idea, defining in every detail the shape and structure of the building. Such yet radical concepts were usually presented through simple diagrams, making it seem as if the design was the inevitable outcome of a rational look at the brief and site conditions. The ease with which these firms developed their concepts – or at least how their work was presented – no doubt made Hertzberger question whether he wanted to present his sketches.

The book Van Bergeijk proposed back then never was published, though not because of Hertzberger’s doubts about his image as a plodder. In hindsight, however, I see some importance in what Hertzberger associates with ‘plodding’.

In this paper I want to examine this importance and will argue that Hertzberger was closer, not only to the reality of architectural design than all these series of rational diagrams (which obviously only be produced after the fact, after the design process is over), but also closer to the political dimension of architecture. Designing is plodding – and architects should embrace that. It cannot be reduced to the inevitable outcome of rational processes, neither is it achieved by a single, more or less divine thought. For even if there is this moment of clear insight, wherein everything seems to be in place, a moment every designer certainly will recognize, this is precisely because already much effort had been investigated and tested into the process, while it only gives reason to thoroughly test, adapt and refine the insight. These moments of plodding, moreover, require the ability to judge what appears on the paper, the little adjustments and experiments – and this ability to judge, I will argue, depends on previously acquired knowledge, tacit knowledge.

In order to examine this perspective of design as pondering, I will use Hannah Arendt’s reflections on thinking and judgement, which she was developing at the time of her sudden death in 1975. Not that Arendt is a great critic or theorist of architecture. She only slightly has touched upon architecture, and certainly never thought of the activity of design as aligned to her notion of political judgment. Her writings, however, first offer a frame to understand political dimension of architecture, while, secondly, her reflections on thinking and judgment enable us to address the activity of design against this political dimension. To my mind, there is a striking resonance between her reflections on the activity of thinking and judgment with the notion of tacit knowledge, as have been developed by Michael Polanyi and others. This paper is not meant to celebrate Hertzberger’s way of doing. Nor do I aim to propel hand sketching on chalk paper above other methods of design. Nevertheless, there is something revealing in the continuous over-drawing of a single architectural detail in order to examine various possibilities by hand. The sheer amount of little (and large) drawings that are produced in this way, everyone articulating a little difference in proportion, a slight change of walls and windows, another option of routing or material. It expresses a glimpse of wrestling with the world, which, to me, is the very political framework of architecture, an framework that might propel a fundamental uneasiness at the heart of the activity of design.

This paper will start by outlining this uneasiness against the background of Arendt’s notion of the political. This uneasiness cannot be fulfilled, I will argue, as it is a signage of addressing the very worldliness of architecture. I take, in the second and third part of this paper, respectively Arendt’s reflections on thinking and judgment to outline an approach to design that, without solving the uneasiness within the design process, answers to this ‘worldliness’ of architecture.

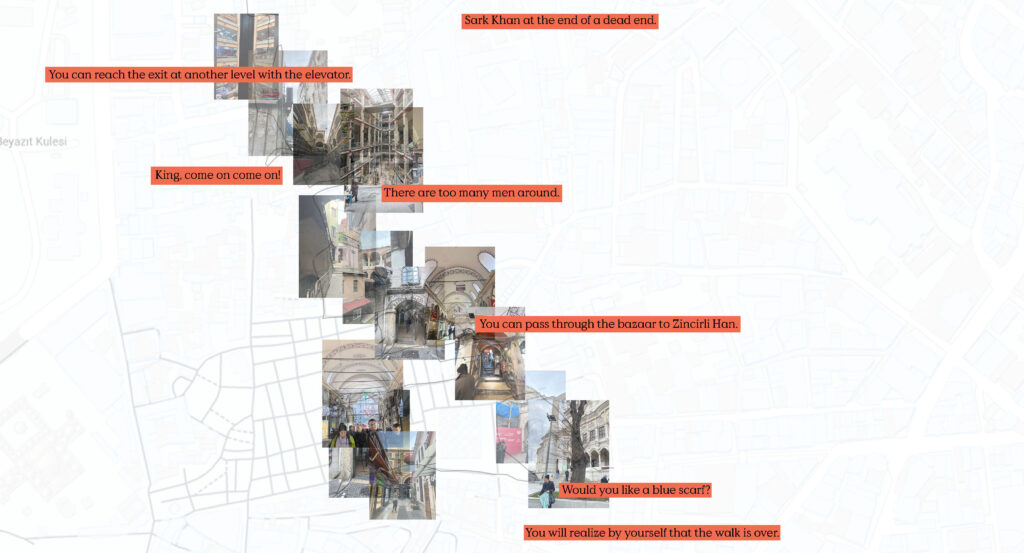

Herman Hertzberger, Sketch Chassé Theatre, Breda, The Netherlands, March 14, 1992

1. The Fundamental Uneasiness of Architectural Design

Not to celebrate hand sketching on chalk paper above other methods of design, especially digital design methods, which are increasingly established, but there is something revealing in the continuous over-drawing of a single architectural detail in order to examine various possibilities by hand. The sheer amount of little (and large) drawings that are produced in this way, everyone articulating a little difference in proportion, a slight change of walls and windows, another option of routing or material, express a glimpse of the fundamental uneasiness that is at the heart of architectural design. In his book The Ethical Architect Tom Spector argues that Bernard William’s concept of ‘the uneasy professional’ offers a valuable entry to understand the profession of the architect. Regularly, he argues, profession is understood as the combination of ‘the skillful application of technical knowledge with an ethic of practice.’

Williams concepts adds to that description the ambition to ‘reconcile societal values with … professional norms.’

The uneasiness comes from the inner conflict that arises out of this ambition, if the societal values cannot be reconciled with these professional norms. Spector sees this happening all the time in architectural assignments – the professional architect is entrusted with the challenge to reconcile ‘private and public rights within the built environment’, which always requires to make difficult choices.

The point Spector is arguing is not that the architect is hired by a particular client, and has to reconcile the wishes of this clients with the interests of others. Rather, it is the other way around: it is society that relies on the architect to represent its interests in the process of design and building. This is an interesting shift in perspective, although it is not necessary to agree upon this theory to understand how the complex design dilemmas in which the often-conflicting interests of different stakeholders have to be represented never leads to easy answers. Architectural design always will fail to fulfil every requirement, in particular when understood against the background of a ‘world-in-common’. For Spector this is the start of his reflections upon the ethics of architecture. I take it, however, to address the political dimension of the field.

With the reference to the ‘world-in-common’, I introduce a term coined by philosopher Hannah Arendt. Arendt, in her work, distinguishes between the earth and the world. The earth is the natural globe, the world is what human beings make from it in order to survive.

The world is for Arendt a world-of-things. Things are both physical, like houses, furniture, roads, and books, as well as institutional, like the political system and legislation. These ‘things’ not only are necessary in order to survive on earth, they also organize life on the globe, both individual life, as well as life of the community. For Arendt it thus is clear that this world-of-things also is a world-in-common. Arendt illustrates this with her famous reference to the table. ‘To live together in the world,’ she writes, ‘means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time.’

An appealing example, as everyone can understand how important this setting of the table is, and what impact the table has on the whole situation. Especially for architects, this is a vivid picture: it makes quite a difference whether you are sitting at the kitchen table with a client, or at a conference table, where a possible client is represented by building managers, project developers, representatives of the financier, and lawyers. Arendt underlines this impact of the world by stressing how the world, and everything we add to it, conditions the human being as well as human communities. Since human beings share the world with one another, they also bear joint responsibility for it, according to Arendt. Whether architects are virtually commissioned to represent public interests or to reconcile public and private interests is somehow irrelevant: to understand how architecture conditions life (of the community) challenges every assignment politically. The fundamental uneasiness of architectural design finds its source in the public dimension of each assignment. Even the hut in the woods or the cabin in the backyard contributes to the world-in-common. Though obviously in various intensities, each assignment thus also has to address the intervention as a contribution to the world.

2. To Think them Anew

What would this political view mean for the very activity and aim of architecture: to design interventions that improve the living circumstances on earth, maintain and improve the world? How can, within a design process, this uneasiness guide designers in order to address the worldliness of architecture? The design process itself is characterized by uncertainty. Design, after all, is not a linear process. It is depicted by twists and turns, persistent problems, and sometimes a breakthrough, unexpected findings and previously un-thought-of perspectives. Those being at home in Arendt’s writings might recognize in this description all three elements of her famous division between labour, work, and action. Design often is labour, going in circles of design, and urged by the mechanics of economical thinking.

It is work, when design leads to something tangible and durable. And design also is action (thought Arendt would disagree with this point), not only since designing certainly leads to unexpected findings, unsolicited insights, but also since the design(process) exposes the designer to the world.

This last one certainly troubled Hertzberger, would the little scribbles not expose him as someone needing extensive labour, before reaching the clarity of his designs?

In her later writings, Arendt also propelled another distinction, addressing what she called the activities of the mind: thinking, willing and judging. Thinking, according to Arendt, is not about acquiring knowledge, but is urged by the will to understand. It is not an application of theory, nor a matter of reasoning, but a form of examining, of assessing and re-assessing a matter or an object that is absent.

Thinking, according to Arendt, is urged by the will to understand. It starts by being in the world, and being struck by something, by an experience of the world that struck home. “Understanding, as distinguished from correct information and scientific knowledge … is an unending activity by which, in constant change and variation, we come to terms with and reconcile ourselves to reality, that is, try to be at home in the world.”

Thinking is to examine, to assess and re-assess a matter or an object that is absent.

It’s a thinking practice, not the application of a particular theory – it differs from reasoning and theorizing.

Political philosopher Wout Cornelissen has traced in Arendt’s writings three forms of thinking.

Though Arendt never conceptualized her own ‘method’ into these three forms, they enlighten three aspects that are important to the thinking practice, and, important to our perspectives, have their resonance in the activity of design. The first form Cornelissen traces is what he calls ‘dialectical thinking’. It is the dialogue between ‘me and myself’, which is distinct from voices around. This is the most common image of thinking in Arendt’s oeuvre. The second motif he traces is ‘representative thinking’, which is an attempt to represent the plurality of perspectives that are present in and constitute the public realm. The final motif is ‘poetic thinking’, in which metaphors are used, which help to understand the ‘object of thought’ from another angle and to open up new un-thought-of perspectives.

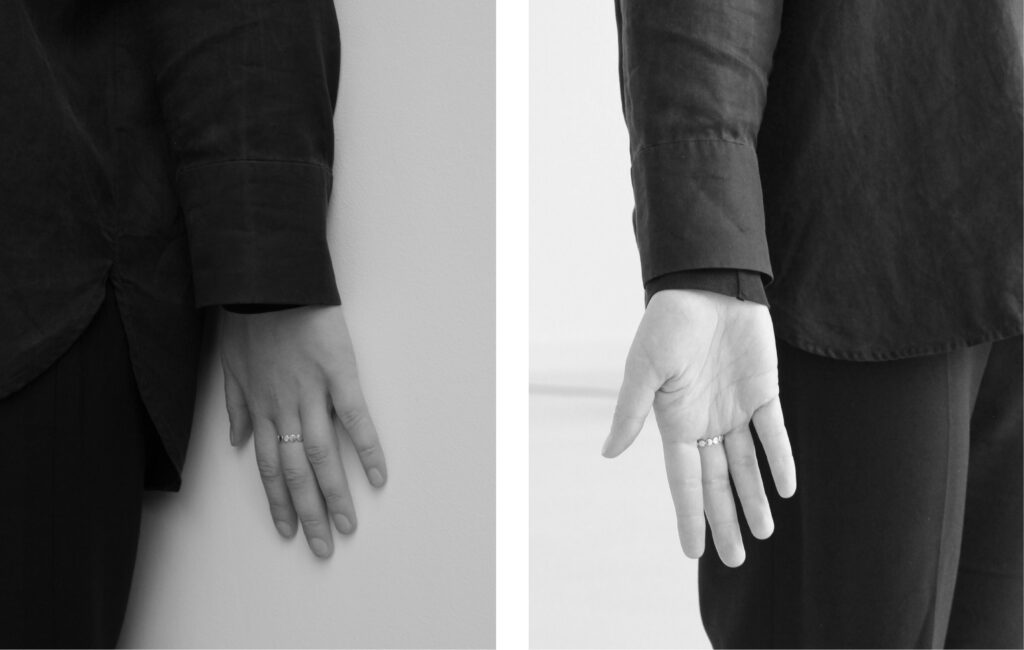

If we draw a parallel between Arendt’s modes of thinking and the activity of design, we certainly see it resonating within Hertzberger’s chalk paper sketches. We first might understand the scribbles as a form of dialectical thinking. This idea of design is certainly the most ‘traditional’ image of the activity of architectural design: it answers to the image of the architect as a person that develops ideas by sketching in isolation. This image stresses a reciprocal relationship between drawing and reflecting, presented in the series of little scribbles wherein only little details shift or more extreme ideas are tested. The hand draws, the mind reflects. Drawing, in this perspective, is the tool through which one imagines the future. The tool becomes part and parcel of the thinking process: the distinction between what is drawn and what is imagined vanishes. The designer does not see just lines on paper, but imagines in his mind the object itself, occupying its spaces.

It is the image of Hertzberger scribbling, pondering in isolation. It is a conversation with un-thought-of turns and surprising perspectives, ungraspable moments of clear insight, and moments wherein it is hard to re-assess what previously seemed clear.

However, this image also is to be contested: it is too limited, and too much focussed on a single architect working in isolation. Design almost never is executed in isolation, as it, at least is to be developed in conversation with a client, an office, with engineers and structural advisors – and, on a more philosophical and political level, with a past, with society, with a knowledge system, with the world. Though design certainly has aspects of the dialectical form of thinking, it is maybe closer to reality to understand it as a representational form of thinking. Even while designing in solitude, the architect is in conversation with others involved in the design process. There are after all meetings wherein the designer presents the design, discusses it with commissioners, future residents and users, developers, politicians, civil servants, neighbours, and so on. The architect will take note of the comments and responses to it, and will rework the design according to this new information. This is obviously even more the case in most of the design processes, wherein not a single architect is designing, but a whole team is involved in the process: a project architect with assistants, structural engineers, light designers, acoustic advisors, designers of the climate system, representatives of the commissioner, financial advisors, and so on and so forth. A project is a constant conversation, a discussion on the essential aspects of the program, the approach to the assignment, imagined solutions, possibilities and impossibilities. While designing, one might argue, the architect (or the team) will (need to) have the client and all other stakeholders in mind, if it is not for ideological reasons, it should be for entrepreneurial reasons (to not run the risk of presenting a project that does not meet the requirements). And as architecture is an intervention in the world-in-common, also this ‘the world and its inhabitants’ should be present at the drawing table – present in the thinking and the drawing, in each dialogue and conversation. In other words, design requires, beyond the capacity to think dialogically, also the capacity to think from different perspectives.

This description urges Arendt’s third motif of thinking: the possibility to think in metaphors. Designing is a form of imagination. This notion of imagination is the capacity, as Arendt states, to think ‘anew’, to imagine objects that are not (yet) there. This capacity, however, does not depend on a genius mind, that can think the un-imagined out of nothing.

This is exactly what can be traced in the sketches of Hertzberger: they might propel an image of plodding, but at the same time, they show that there is a certain skill at work, a clear way to represent and test ideas. These sketches are clearly propelled by experience and insight. In other words, imagination is fuelled by precedents (architectural history, tacit knowledge) and craftsmanship (skill and experience).

By taking architectural knowledge, that is the language of architecture as it is inherent in precedents, in concepts and spaces, in elements and structures, in materials and techniques, and transferring these to the particular assignment at hand, the designer grasps experiences in order to ponder them in the mind, as well as establishes a correspondence between the design at hand and the reality of the world.

This perspective brings us close to the notion of tacit knowledge, or better said, to Giblert Ryles notion of ‘knowing-how’. Knowing how is not urged as an intellectual knowledge, but a knowledge that is rooted in a practice, in an actual doing. Knowing how is thus an informed thinking, it is embedded in experiences from practices, and accounts for principles, standards.

This is what Ryle adds to the thinking-perspective in relation to actual design processes: this thinking does not come from nowhere. As practice, it is informed by previously gained experiences, by particular standards, principles, codifications, uses of the field that have been incorporated in the practice of designing itself. Or, to state it differently, by tacit knowledge.

The sociologist Robert Gutman has stressed how such a design-process somehow ‘hurts’.

Gutman’s remark mirrors the uneasiness Hertzberger felt, reflecting on all his struggles that are clearly exposed through his sketches. I would argue that it is actually an important aspect of architectural design, a signage of engaging with the world that is plural, and engaging with it from various perspectives. Resisting the temptation to oversimplify, to generalize, and to extrapolate (and thus to reason), design is a process wherein increasingly more complex questions need to be addressed.

Therefore, design requires the ability to deal with ‘twist and turns’, to put ideas aside, to not simply rely on previous experiences and skill, but to also start all over again.

Designers thus need to be critical, not only to the assignment itself, to the context or the commissioner, to the system of financing or the ambitions of a municipality. They also need to be self-critical, being able to examine their own ideas. Designers should not be satisfied too easily with their own ideas.

3. To Design is to Judge

But to describe design as a form of thinking only does not do justice to the very process of design. Design, after all does not aim to understand, but is meant to propel ideas, and to present objects that are not yet there. This means that while designing, one needs to accept certain conditions and decide which possibilities offer the best opportunities. Though such moments of decision seem to stop the process of pondering, they are still depicted by uneasiness. After all, it hardly happens that a singular decision does right to all the various interests of stakeholders, let alone to more or less ungraspable political, ecological, and ethical ambitions.

Arendt offers an intriguing view upon the human capacity to judge, which one needs in order to be able to decide. She in particular retakes here a perspective from philosopher Immanuel Kant, which ideas on aesthetic judgment she takes as a model of judging politically. Although she could not elaborate her first notes and lectures on her interpretation of Kant because of her sudden death in 1975, there are a few perspectives that also are valuable within a frame of reflections on the process of architectural design. Her view on judgment is close to her second category of thinking, representational thinking. While judging, one needs to deal with a reality that is characterized by plural perspectives. She urges three perspectives that to my mind open up a valuable perspective upon the activity of design as well.

First: Judgment does not happen in solitude, nor is it an individual matter. It is political, and thus needs to deal with these other perspectives and strives for a certain agreement. Arendt therefore argues that one, before one can judge, needs to ‘to replace oneself, to think in the place of everybody else.’

Though Arendt does not mention her metaphor of the table here, it is helpful to take it again as a point of reference. Everyone seated at the table sits on a different position, and thus inhabits a different perspective. Arendt nevertheless stresses the importance of the table, which is shared. Having the same object in common, but seeing it from a different perspective, reveals something of the complexity or the world. Or better: it establishes the experience of reality: ‘Only where things can be seen by many in a variety of aspects without changing their identity, so that those who are gathered around them know they see sameness in utter diversity, can worldly reality truly and reliably appear.’

This perspective comes close to Polanyi’s emphasis on the tacit dimension of personal knowledge: it is related to share knowledge, but still colored by one’s own position in the world, one’s own background. However, Arendt not only suggests to acknowledge these different perspectives around the table, but literally urges to replace oneself ‘to think from the standpoint of everyone else’, and from there on also to ‘reflect upon one’s own judgment.’

Only by doing so, one can reach for agreement with others.

Judgment thus is in a continuous conversation with others – and if they are not present at the table, it requires the faculty of imagination to make them present, in order to be able to listen to their voices.

Second, judgment seeks for a common ground, a possible agreement amongst one another.

Judgment thus is in a continuous conversation with others, but moreover depends on the faculty of imagination to see for oneself (to experience for oneself), in order to make an informed decision, that probably can even reach agreement.

One is able to replace oneself, not because of speculative thought, but because of the existence of a ‘common sense’, which to her is not an extra mental capacity (of the mind), but literally as a sense for the world, rooted in a human communities. As the object of judgment is brought in conversation with various communities it needs to address, and continues to ponder various possibilities before deciding upon the best possible outcome, it also can be expected that the decision is communicable to a wider audience. So this is an important premise of Arendt: Judgment does not search for ‘truths’. It searches for agreement. And even if, in the end, not everyone agrees upon the judgment, the reasons can be made explicit, communicated. Common sense for Arendt thus mainly is ‘community sense’: it is shared within a particular community.

Arendt brings in here a reference to the faculty of taste, which plays an important role in Kant’s model of judgment.

Taste, she writes, is the human faculty that enables to ‘decide what the world qua world is supposed to look and sound like, how it is supposed to be looked at and listened to.’

This idea of taste is not simply intuition or a talent for beauty, it can and needs to be trained and enhanced. In such a way, it (again) only functions within a particular community. This point is for Arendt very important, as she underlines how judgment needs to be communicated. Judgment can be communicated, explained and defended to the community as a whole, while it also is open for dispute, as long as it is based on this act of displacement.

This notion of taste somehow suggests that there is a need to explicate the tacit knowledge that is at work in the design process. To make the knowledge that steers the decision accessible, so that it can be discussed. However, Arendt also describes it as a ‘silent sense’, which somehow addresses the impossibility to make taste as well as tacit knowledge, explicit.

The last point Arendt propels is the idea that an informed judgment or a possible agreement is similar to finding the middle point where all perspectives cross. It is not about finding the average of all the data entered in a model, nor to pick the most effective, most optimal point out of a computational simulation. From Kant she takes here the notion of taste, which is, for him, not subjective, but a certain shared and trained knowledge, a knowledge shared within a particular community, that is able to differentiate between what is good and tasty, and what is not.

It is not too far-fetched to see here a nice resonance between Arendt’s reflections on judgment and the activity of architectural design. Also political philosopher Seyla Benhabib somehow understand how this idea of judgment is present in fields of for instance the arts and medicine.

To bring it to architecture: Design intervenes in a certain community – or better said: each design needs to address multiple communities: the ‘community’ of the design team, the context of client and market, the community of (future) inhabitants, a community depicted by a street, a housing corporation, the wider community of experts, and last, but not least also the community I call ‘the world and it inhabitants’, which is the very political community. To design requires decisions, judgment over all the materials, insight in how the various communities can be addressed. With Benhabib we can argue that, in addition to Arendt’s model, there is an ‘architectural body of knowledge’, which steers the design towards certain directions.

In comparison to the public, the architect is educated, experienced, and trained in order to think spatially, and has a body of references in mind while pondering upon a design decision. The architect knows what it means to draw a line. In design, we might argue, that the combination of (developed) taste, skills, and knowledge helps the designer to judge more quickly, to trust intuition while reading a drawing, visiting a site, talking to a client, and hearing comments from a particular audience. But to only rely on these required skills and intuition would not do justice to the uneasiness of architecture for two reasons. First: decision-making in the design process is never neutral. Design has to deal with conflicting perspectives – the interests of clients and users, financial institutions, wishes of municipalities, the interests of neighbours, the advises of structural engineers. But since architecture also is political, as it intervenes in a world and will condition life in and around it, for decades, it also needs to acknowledge this perspective of time, of a future world and its inhabitants. This is the perspective of ecology, of society and its challenges, of cities in development. Architects need to be able, at the drawing board, of course to look to their designs from the perspective of the users and the neighbours, but also from the world and its inhabitants. Not just to make these voices present, but really to inhabit these positions. To seek for the agreement, not only at the end of the process, but also along the way. And second: architecture cannot just fulfil the wishes of a singular community, or think solely from an architectural perspective about the world, without not also seeking agreement in other communities. Arendt’s model of political judgment is valuable in this respect, as it urges the necessity to seek for agreement, to root itself in a community, and to value the necessity of communicability. This model of architectural design = political judgment allows the architect to involve ‘the public’ even in the first sketches. The horizon of the public is not something to add to his ‘thinking’, but is at the core of all design ‘thinking’. To design is to assess all sorts of information, and to look from different perspectives – to (almost literally) take the position of other stakeholders, and not in the least, also think from the perspective of the world and its inhabitants. Although the public is not literally at the table, the architect still has to find ways to make them present, to imagine his project as part of the world, in the moments of decision. Imagination of course is central in this process of architectural design. Architects are required to imagine the future and to dwell upon possibilities of use and engagement, to imagine the public and what is convincing from the public view, to imagine the past, and how architecture takes care of it, to imagine the world and to understand how the intervention maintains the world as a common entity.

Only by replacing oneself, the architect will be able to capture the different knowledge systems of the various communities wherein the building will function. It needs to be addressed, also to come to an agreement about the intervention. The ‘agreement’ that the designer is seeking, however, is not the average outcome of every perspective at the table (or made present through imagination), exactly in the midst of all other places around the table. It does not search for ‘truths’ nor does it expect ‘objectified’ judgments or a perfect balance between different viewpoints. To judge is to take the various perspectives into account, including the own perspective. But one of the important perspectives is certainly also the own architectural knowledge gained in years, the tacit knowledge, gained by training skills and enhancing intuition. This is the knowledge how, we touched upon before. It is personal, but also shared amongst other practitioners, though without being able to bring it to a formula, nor handbook. This is the intriguing aspect: this body of knowledge is not based on closed theories, mathematical rationality, or any other fixed standards. It is a responsive knowledge, as it always has to deal with particulars: different locations, different conditions and histories, conflicting interests. Therefore, this tacit knowledge will respond and relate to all the various perspectives contained in the assignment. And as it is brought in conversation with the various communities it needs to address, and continues to ponder various possibilities before deciding upon the best possible outcome, it also can be expected that the decision is communicable to a wider audience. The architect, in other words, needs to go out in public, needs to appear amongst others, in order to explain the architectural proposal, not only at the end, but also along the way. It is inviting the public to become participants in the process, not only by imagining them as participants around the table, but literally seeking for their agreement. This is evidently a moment of unpredictability and vulnerability. To present the design is to make oneself vulnerable to the judgment of others. However, it is necessary to involve the public into the project, as it is not only the life of the users and inhabitants, but also the life of the community that will be affected by the intervention.

A final important note: to design is not similar as finding the middle point where all perspectives cross. It is not about finding the average of all the data entered in a model, nor to pick the most effective, most optimistic point out of a computational simulation. Design does not search for ‘truths’ nor does it expect ‘objectified’ judgments or a perfect balance between different viewpoints. In order to be able to judge, one need not only to know the various perspectives at stake, one also need to be able to value them. It requires knowledge to evaluate the perspectives, and to take a decision.

The architect has an expertise that needs to be brought into the process as well. The architect is educated, experienced, and trained in order to think spatially, and has a body of references in mind while pondering upon a design decision. The designer knows what it means to draw a line. In design, we might argue, that the combination of (developed) skills, and tacit knowledge helps the designer to judge more quickly, to trust intuition while reading a drawing, visiting a site, talking to a client, and hearing comments from a particular audience. To refer to the Harry Collins: we might understand Arendt’s remark on taste as the ‘specialist tacit knowledge’, in the form of contributory expertise.

However, it is clear that this model requires an ‘architectural body of knowledge’, which steers the design towards certain directions.

This, of course, is very well visible in the series of sketches of Hertzberger too: it is always the combination of the designer in conversation with himself, but also with others, bringing other perspectives at the drawing board. Sheet after sheet, a new challenge is on the table – and he examines it in conversation with others, responding to his employees, to his clients, to his advisers. The construction is explored from various perspectives: structurally, technically, materially, and aesthetically. To judge is to make an informed decision – but this decision is not just informed since one has replaced oneself to all possible other positions, interests, perspectives. It also is informed by a body of knowledge, by a knowing-how. By a personal knowledge, which nevertheless is not just individual but social, shared amongst other practitioners, though without being able to bring it to a formula, nor to a handbook. It is the knowledge of a social practice, shared with one another, even without words. This is the intriguing aspect: this body of knowledge is not based on closed theories, mathematical rationality, or any other fixed standards. However, to only rely on these required skills and expertise would not do justice to the political dimension of architecture. Therefore, to me, Arendt’s model of political judgment is valuable to keep in mind, as it urges the necessity to seek for agreement, to root itself in a community, and to value the necessity of communicability.

4. Epilogue

While Hertzberger was afraid of being understood as someone who has to work hard for his designs, he has also always resisted the image of the designer as a genius. Hertzberger’s own working method does show precisely the advantage of pondering. How he goes over the project again and again, in order to consider various options, and to explore multiple perspectives. The very act of drawing various proposals and opportunities, and examining them from different positions helps the architect to bring different perspectives into the project, and to imagine the intervention as part of various communities. It is the only way to already from the very start introduce something abstract and absent into the project: the public. The world in common. Plodding establishes a correspondence between the design at hand and the reality of the world. This requires at once the ability of representational thinking and imagination: what does it mean that this object under design will become part and parcel of the human condition and will structure human communities extensively? Even if this can be understood as plodding.